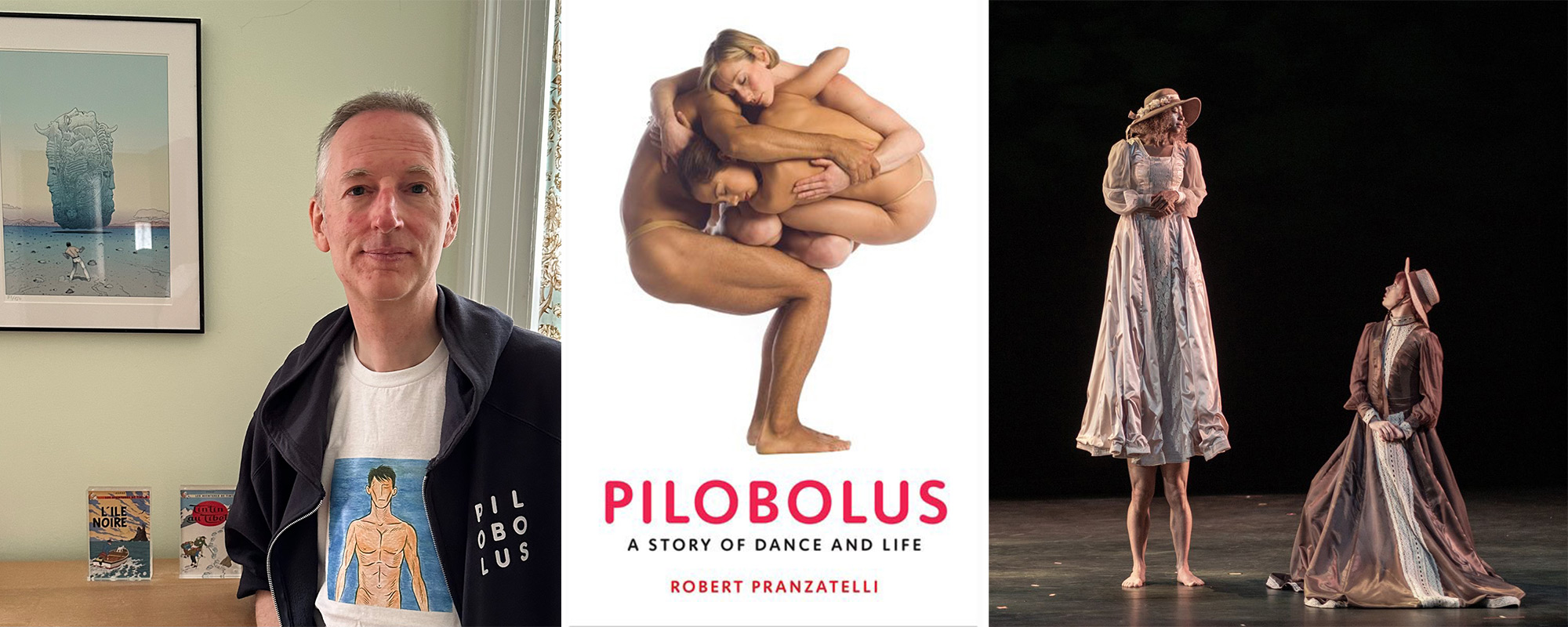

Author, publicist and partially involved narrator Robert Pranzatelli joins the show to celebrate his amazing new book, PILOBOLUS: A Story of Dance and Life (University Press of Florida). We talk about the origins of the legendary Pilobolus dance company, his transformational first experience seeing them in 1997, the workshops he took with them and the friendships they engendered, and the "itchy fingers" moment when he realized he had to write their history. We also get into Pilobolus' unique melding of improvisation and dance technique, the joyful challenge of describing their dance pieces on the page, the importance of capturing the time capsule of Pilobolus' '70s roots (and covering All The Affairs, along with the friendships and fallings-out), how Pilobolus was taken seriously by dance critics long after audiences flocked to them, the company's through-line in its 50+-year history and how they managed to continue the tradition of something that was based on overthrowing tradition. Plus we discuss Robert's history as a writer, how Metal Hurlant & Moebius blew his mind as a teen, how he became a book publicist at Yale University Press, his narrow-focus mode of reading, his greatest eBay score, why he got choked up while reading a text he sent Pilobolus' artistic directors after a performance, and more. More info at our site • Support The Virtual Memories Show via Patreon or Paypal and via our e-newsletter

The Virtual Memories Show

Episode 594 - Robert Pranzatelli