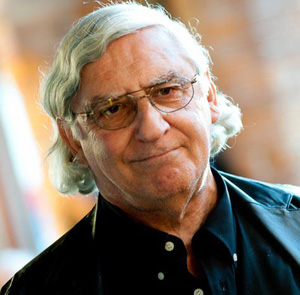

Editor, writer, publisher and translator Maxim Jakubowski talks about his lifetime & career in erotica, how he feels about being The King of the Erotic Thriller, his strategies for maneuvering through Book Expo America, the silliness of genre labels, the perils of having a bad book habit (that’s "bad book-habit", not "bad-book habit"), how e-books have amplified Sturgeon's Law, how he managed to make a killing off the 50 Shades of Grey phenomenon under a BDSM pseudonym, and MUCH more!

The Virtual Memories Show

Season 3, Episode 27 - Sex, Crime and Other Arbitrary Genre Labels

[MUSIC] Welcome to The Virtual Memories Show. I'm your host Gil Roth and you are listening to a podcast about books and life, not necessarily in that order. You can subscribe to the show on iTunes and you can find past episodes, get on our email list and make donations to the show at our website, chimeraobscura.com/vm. You can also find us at facebook.com/virtualmemoriesshow on Twitter @VMSPod and at virtualmemoriespodcast.tumbler.com. Our guest this time around is Maxim Jakobowski, and I encountered Maxim many years ago when I was a small press publisher. He wrote to see about using an excerpt from one of the books we published for that year's Mammoth Book of Best New Erotica. I couldn't remember anything about mammoths having sex and anything we published, but I figured I'd give him permission anyway. I followed up and found out more about his work as a writer and editor and publisher and translator. He's really covered so many different fields in crime and science fiction, erotica and a lot more. I figured he'd make a great interview sometime for whatever venue I was going to have down the line. So I always had him on my list of interesting people I know, and that's the sort of thing that I always figured would come in handy, and once I launched a podcast, I was proved right. It took us a while to get together since Maxim lives in the UK, but we finally had a chance to meet and record when he was in New York for Book Expo America last spring. It's a great conversation with someone who's been involved in every aspect of book publishing for decades now, as I said, across a whole bunch of different genres. One of the lessons I've learned from doing this show is, you know, storytellers got a storyteller, and Maxim has some really great tales about his history and his current doings and how we discovered erotica and it's not so seedy side. Well, let's say literary side. Like I said, he's really carved out a singular career for himself without ever having to compromise his writing. I think you'll take this conversation a lot. And now the virtual memories show with Maxim Jekobowski. I just want to start with the fact that we're recording in New York City and you're here for Book Expo America. What are your expectations for an event like this? What's... Why are you here, I guess? Well, I've been coming to Book Expo for, I think, nearly 30 years now. In fact, when it was still called, V-A-V-A-V, American Books and Association Conference and Show. And in fact, when I came for the first time, I was one of the first British publishers to overcome. We were few on the ground and I've been coming back ever since. I don't think I've missed a single year. The reason I come is different. I used to come because I used to work in publishing and it was a useful way of seeing what was happening on the American scene, meeting people, publishers, authors. And now that I no longer work in publishing full time, it's become a habit or, god I see, a vice. Yes, I see publishers, I see other authors. And it just gives me an opportunity to test the temperature of what's going on. I also used to go to the Frankfurt Book Fair and when I left full time publishing some years ago, I decided I would never go to Frankfurt ever again. I have to go this fall, trust me, I'm not looking forward to that at all. I went two hours ago for a show. I mean, Frankfurt is hard, it's business, business. The food is awful. And I've never felt comfortable in Germany somehow. And I even miss out some years on the London Book Fair, but V-A I never miss out on, because there's also, of course, another reason. One of my many vices is I'm a book collector and unlike all other book fairs at V-A, the big publishers give away advanced copies of hundreds and hundreds of books, mostly fiction of all the big autumn books. And even though I know that three or four months later, I would be able to get most of them from British publishers in the post or by just giving a phone call. I still like being through my bad BA and shipping and shipping a few boxes of books back every year. Many of the boxes are still virtually unopened at open, piling up, but I'm afraid I have a bad book habit, but on top of that I can justify it because, of course, I see everybody and it does give me ideas sometimes. I believe there's no such thing as a bad book habit myself. How is today? Did you go for today's show or are you starting to go? No, whatever show starts tomorrow morning, today is just the pedals and conferences, which I don't normally attend. What books are you looking for? You never know in advance. I mean, some publishers I know what I know that I think Little Burn will be giving out the new Scott Turo, which comes out in October. I know Viking will be giving out the new, well, the second, Mooie Sepeshel, who did, oh, that's very interesting, but I come up with one of those long titles with physics. And the new one is a sort of literary thriller, which sounds quite interesting, although I think that's a good chance that by the time I get back to London next week, I'll already have a British proof in the post, but as I said, if I see it, I will pick it up. An attic is an attic, I guess. Oh, totally. I even plan my BEA in so far as for the first hour and a half, I never make any appointments. I just run around between the stands picking up the proofs and then dropping them with a shipping agent with whom I have an agreement and they ship them back after the book fair. So it's a vice. And enough of the publishers know who you are at this point? Oh, yes, no, no, no, well, basically everybody, I mean, the books I've had to be picked up. So I mean, you don't even acknowledge who you are, you just pick them up and they are free. Now, you say you've gotten out of publishing, but you're working as an editor for a number of of anthologies and books. What have you seen from the editor's project? I believe your main focus is on crime writing and erotica, am I missing another major? In terms of my editing, no, those are the main areas, yes. How have those fields changed or what are you seeing that's different from authors neither of those areas? Well, crime has always been incredibly popular and it's always been a very, very important segment of the publishing market and it's been solid and it keeps on being so it doesn't really change, new offers disappear, new offers appear and it's always been a very important segment. And for many years it was almost confidential until, of course, the Fifty Shades of Great Tsunami, which anybody who was involved in erotica before still cannot understand. I was down on my list of questions in what on earth is. I mean, for me, it was basically, I mean, thank you, E.L. James, what she's done for the field, but the books aren't in atrocious. I mean, I read a chapter and a half of the first one before I almost threw it against the wall because it was an insult to good erotica, however, it caught on with the public. Even though, A, they were badly written, the characterization was absolutely as a nine, I mean, if you, well, she was 23 or 24 year old Virgin who lives in Seattle, or a billionaire, billionaire, or millionaire with a heady pad, I mean, it was totally unrealistic and even the BDSM parts were nothing new, it's been done better over the years by scores of people, I mean, from story, although onwards, to Anne Rice and many, many others, why it took off? There are hundreds of theories, I don't have any. It was cool. It was a big end in England at all because here it was huge everywhere. I wasn't sure because here it was apparently one third of all books sold for several weeks were just books. I think in England, and in most countries I know, for other reasons I know obviously the statistics very well, it represented nearly between five and ten percent in some countries of a total book sales fall last year, and of course it's launched a hundred bad imitations and the real erotic writers have still been left behind, or most of them have, most of them have. What makes good erotica? If only I knew. You better not have anthologies? Well, basically, I'm not a theorizer, I'm basically lived by the principle of that. If I see it and I like it, then it is good, and that was the same when I was in publishing. I don't try, and even though I was educated in France where obviously literary theory is quite advanced and very theoretical in England, it was true. I was very much in the minority then, and I still am, but I try not to theorize. I mean the amusing thing about the new wave of erotica spurred by the Hill James phenomenon is that it appears to what they call, obviously, what they call it, in some countries they call it mummy porn, and it is, first of all, I didn't believe it, I thought it was just an easy marketing term that the publishers, sales and marketing guys had come up with, but in fact, it is true, because in fact, a few months before the ill James wave struck, I was contacted by one of the publishers who said there's something in the air, there's something coming up, there's a spot coming up, we haven't read it, or in some cases some of the people were the underbidders for the book, and I thought, well, maybe we should commission something, to just in case it is a success, so we are, we've got to go to catch a wave just like when Patricia Cornwall brought through with, yet again, something which wasn't original for Enzig crime, very quickly you had lots of other people, including Kathy Reichs, and Betsy Caldwell and ourselves, millions, and Kathy Reichs sales, maybe one third of us millions, but, and a few quite a few other people, so I was contacted, in fact, oddly enough, I had a London book for last year, by actually two publishers who said, oh, you've been writing a writing about some time, and we never read my writing, and we gather it's well written, it's quite literally, and I said, yes, that's a whole idea, would you be interested in doing something for us, and my initial reaction was no. Basically, for the last eight or nine years, I've been alternating one, well, not really one year, but every 18 months, maybe a crime or thriller novel, albeit with erotic elements, because that's what I do, and a purely erotic book, and last year was going to be my year of writing a thriller, okay. And actually, I was thinking of doing a thriller and cutting out all of your erotic elements, because I wanted to slightly renew myself, I had so slightly burned out over the series of four or five books, which were all treated, they're treating the same themes, or the same obsessions, as most writers have, and then I gave you some thought, and then I said, well, I'll give it a go, I had a chat with my agent, and came up with something, and which I thought, by then I'd thrown my copy of Fifty Shades of Grey Against the Wall, and thought well, yes, I can do better, I can write better, and I could also make character as much more realistic. I came up with an outline, and my agent took it, and sent it out, and said yes, she thought that this could actually sell. Well, of course, I mean, I've never made any secret, and my autica over the last 20 years, I mean, my own novels, not my collections. If I sold five, if I sold five, if I sold five to ten thousand copies over the lifetime of the book, I was very happy. But it never meant to be big sellers. I've never had to make a living for my writing. So she said, well, I did three sample chapters, and then thought, if I do any more, all I'd be doing is a parody. I'd brought in a very close friend, whom I also published in my collections, another writer who I feel was on the same wavelength, and we revised the chapters, gave them to my agent. And the book went out, well, the proposal went out, it was the proposal for two novels, and the proposal went out to the ten major mainstream British publishers, and they were told, well, you've got two weeks, if you want to make a lot of it. Within forty eight hours, one of the big publishing houses came in with a floor, and then she rang everybody saying, no, no, you've only got another three days, because obviously they're suddenly very interested who wanted it, and a few people dropped out, including Random House, because they had fifty shades. And there was a bidding war, and I think one hour before the end of the auction, Harper Colleagues came in out of the blue and said, we'll offer twice as much as the previous offer, but can you make it a trilogy, which is what we didn't want to do, because we didn't want to do a trilogy like Fifty Shades of Grey. Anyway, but the money was so major. I mean, it was the biggest advance I've ever been offered in my life, or bigger than ever. I'd been in a position to offer when I was working to any author. And my co-writer was not as financially comfortable as I was, so we said yes, but we said, but we haven't got a clue what's going to happen in the third book, because the outline is for two books, so you'll have to take it on trust that we can do the third one and it'll be good. And then we said, well, okay, and then the publisher who had the floor came back and said, that's a lot of money, but we'll match Harper Colleagues because we really wanted, but we're not getting higher, and they won the auction. It was a huge six-figure auction for three books. Then the problem was, this I think was mid-May of last year. We said, could we have volume one by end of June, because we want to publish end of July? I was just about to leave for New York, when I was in New Orleans, when I was in the Caribbean, and then I had trips to France and Italy doing that period. So it was basically written in hotel rooms, probably one third or something. And the computers, where you're sitting now. And we delivered, and obviously we were emailing each other, we did. We structured the book, and the book came out. It's under the pen name. It had to be under a female pen name. Mainly for marketing purposes, as opposed to any embarrassment or argument or embarrassment over what it is. That's the marketing people dictated. I mean, half of a bit of publishing knows who the authors are. Although we can't afford to release. It's now a year and a half later. We've now done six volumes, just delivered in fact volume number six last week. All these subsequent contracts were an extra two, and then an extra one were well into six figures. It sold to 31 countries. We've now sold three million books. And it has to come out in one third of the countries, or not all five volumes. The sixth one comes out in September. How do you feel about that? Very grateful to E.L. James. My grandchildren will be very happy with the money, because I have a house with 11 rooms. I have all the books that I want. I have all the CDs that I want. I'm not a close-oriented person. My only collections on my CDs are buy books. I mean, the money has been absolutely incredible. But the amusing thing is that Americans, the only country we ever have been best sellers. In fact, right now, four out of the five books are going to be German Top Ten. As of this week, Germany have done nearly one million copies of the five, which have come out so far. And this is at 14 years each. In England, they came out as small paperbacks. But in Germany, they did them as big expensive paperbacks with flaps. So they're 14 years and they will still come out in the future as mass market paperbacks. So very grateful to E.L. James. I mean, initially when the books came out, I mean, the American publishers were very wary, because I said, "This is not quite E.L. James." Because it's much more explicit, and the BDSM element is very strong, not from my research, but from my co-writers' research. She has been involved in the BDSM scene. So it is quite authentic in that respect. But essentially, the books are not very different from what evil of us were writing for years and years before, but they just came at the right time. And money was spent in the motive. I mean, they've won third of the BDSM, they've gone through supermarkets, who have been bookships, which has been fascinating. Yes, indeed. But of course, we have a Facebook, our pen name has got her own Facebook page, and you should see the facts and all the likes. They're all women between the 30s and the 50s with children. Half of them can't spell. I'm about to infuse estimated love with books. I mean, we love our readers, but it is the money market. Wow. Have you ever imagined you were going to be? Absolutely not. Absolutely not. I mean, right now, both of us. I mean, my co-writers absolutely exhausted, because she also has a full-time job. Well, she's now one part-time, because she's now bought us over house on the proceeds of the first few volumes. But the market is now falling fast. So that last year, I mean, I said, in America, America's the only country where, I mean, the books have sold over here. They've done about 30,000 copies each, which is not bad. But I said, in England, the first volume is on 600,000 copies in Germany, 700,000. We're number one in Argentina this week. We were number one in Poland a few weeks ago. So, I mean, our pen name plus Silvia Day, who's a romance author who was published very quickly after E.L. James. And E.L. James, we're the three who control the market. None of all the other imitations since have not broken into any of the bestseller lists. There was a book which went for quite a bit of money at Frankfurt called Secrets by it's a pseudonymous Canadian author, I don't know who, under a pseudonym, L.M. Adeline. And Secrets is Volume 1, there'll be a second volume in September. I gather it went for a lot of money, and our publishers were worried, because it came out at the same time as I think our third volume didn't get into the, even for top 50, two weeks ago, VX porn star Sacha Gray published her first novel called Virginia Society, which in fact is okay. I mean, it's disappointing, but she has got a voice, and that's really interesting, if she has written it, or it hasn't been written by... She was one of those most academic porn stars as opposed to... But the book has got a voice. It's got a slightly raman, a female raman charm risk voice, but the plot itself just falls apart halfway from the book, unfortunately. And I think, in America I don't know, I haven't seen it on any of this. It only came out two weeks ago. In England it went in at number 49, and we're doing three and a half thousand sales in the first week. Keeping an eye on the Erotica charts. How did you get started in Erotica? I mean, with Jacqueline Smith and Charlie Zangel's back when I was a kid, but you know, that's a different story. Yeah. I don't know, maybe I was pretty supposed to it. I don't know. I mean, as a teenager, I was heavily into science fiction. Science fiction is where I began. It was my passion. And I read quite a lot of crime. And I think the only reason I liked crime when I was in my teens, because unlike science fiction, obviously, since there have been some science fiction authors who have got, obviously, a fairly reasonable treatment of sex, like Philip Farmer, Chip Delaney, and others. But crime was sexier, even though in many cases of a door closed when the mole and the private eye basically put one foot on the bed and then it moved him in the next chapter. But you could imagine. So, maybe that sort of attracted me when I was a teenager. And I didn't come back to crime for many years after that, but I started writing science fiction when I was in my teens. I published my first book in France, because he was written in French, because I was brought up in France. And there were sexual elements. Maybe not one of them I published when I was 16. But later, which is why my science fiction lived really so very well. People were saying, "What do you need for sex?" And the editors and the readers. So, eventually, I'm more or less drifted out of science fiction. I remained a fan and editor. And I occasionally do a short story here and there. And I've done anthologies. But then, purely because I was brought up in France, obviously, I read a lot in French. And I'd read a lot of the French classics. And there is a wonderful tradition of literary, erotic, and France. Long before the story of Rome, and Apollinaire, Chagorps, and many other authors, I well-known what I would term "main street" authors, have all written "Erotica" at one stage, maybe just a one-off or just a one-or-two book. In some cases, under pen names, which were later revealed, or even under their own name. And it's always been acceptable in France. So, I found it quite interesting. And I delved into, I don't know, sex and he wanted to go and found it rather boring. I mean, basically, particularly in the UK, it's the traditional, upstairs, downstairs, master, servant, spanking. And I dare say, without giving too much away about my own sexual taste, but spanking doesn't do it for me, either as spanker or as spanky, which is the technical terms. It's good to know. And then, one day, and this comes back to science fiction, there's an English science fiction writer called Ian Watson, who's got quite a good reputation. And my wife and I were living in Northampton, north of London, and found out that I started corresponding with you, and maybe it sent me a story. And his first novel, The Embedding One, the Alpha Sea Clark Award, was published in France and did better in France than it did in England. And we invited to dinner to his play. He was living in Oxford at the time. We went to dinner there, and as I do in anybody's places, I was looking at his bookshelves. And he had a whole shelf of all the Essex House titles. Essex House was an imprint done in the '60s, just after, I think, the Superim Court allowed more explicit books to be published as an outshoot of basically a fact book publisher called, I think, Brandon House. So you wanted something more respectable, because they were hoping they could get them in real bookshops rather than petrol stations or whatever. And, of course, that's where Philip Farmer published his erotic books, The Image of the Beast, Blown. His sexual Tarzan book, Harlan Edison, was going to write one at one stage, ship to land. He wrote Tides of Lust. Above the time he wrote it, the publisher no one had already dropped the imprint. A lot of books were published elsewhere were actually written for that imprint. They were contracted through Essex? Yeah, they were commissioned. Because there was a guy called Brian Kirby, who was a San Francisco poet. And how he was put in charge, I don't know. I mean, he was quite a well-known local poet, but he was told, can you commission some more intelligent books, basically? And he went out in the commission, lots of friends, lots of local poets. David Meltzer wrote a whole series of books. There was a New York way now that lives in a boardstock poet called Michael Perkins, wrote a whole series of books, including one called Evil Companions, which is one of the best of what it was of all time, which I've been happy to be able to be published. In fact, nearly a third of the books I've been published in the member list initially came out with Essex or else. I couldn't do the farmers, because, of course, being a farmer, the agent that rises them elsewhere. And, as I said, even once it had a whole shelf in England, I managed to get hold of the farmers in a small hip book shop in London. And basically, they were impossible to find. They were sort of legendary and at the time, there was no such thing as the internet to do research search for books. And I never found them when I was traveling in America. And Ian had the whole set, all 35 volumes, because at one stage he was teaching at the University in Tokyo, and being part of the expat community in Tokyo, he had access to the local American base. And was it the PX stores? Yeah. And at Baltimore, out there, out of curiosity. So I said, "God, I want to read all the others." It was Hank Steins, the season of The Witch, which has been republished a few times, which I think Chip Delaney wrote a big blurb for that one. And some lesser books, but a lot of books were people who were involved in science fiction, oddly enough, Charlie Plattin, who is a friend of mine, Mark Oggs, in London, about three, which were later published by Ophelia, as one of the offshoots of Olympia Press. So it was quite a legendary period. It lasted 18 months, but some of the books published were absolutely wonderful, because I think what they did is they showed me that you could write a vortico without pandering to the lowest common denominator. You could have plots. You could have characters. And some of the books were not as interesting, but at least half of the list was absolutely wonderful. And Ian, who was then the features editor of the Small Academic Science Fiction magazine called Foundation, which was published by the Science Fiction Foundation at Northeast London University. And I said, "You can borrow all of them, but on one condition write a piece about the imprint for the magazine," which I did. So I wrote a piece for Foundation once I'd read them, an enthusiastic piece, and then managed to make contact with Michael Perkins in Woodstock. With David Nelson's emphasis, again, we become, in fact, very good friends. Then Michael Perkins's daughters stayed with us for many years, and Michael and himself went there in London. And basically, let's stay in my mind that a vortico was like any popular genre, like science fiction, like crime. 90% of it is of sturgeon's law, 90% of it is crap. But 10% of it can be bloody good. And to cut a long story short, by then I was still in publishing. I mean, I couldn't publish it myself. The companies I was working for was no way I could publish it once again. I mean, I was publishing William Golding. Peter Eustinov, Peter Aykroyd were amongst my authors. So I think I would have been shot down at the weekly editorial meeting, had I even suggested doing a vortica. And basically, I was doing a voccasional anthology for Nick Robinson, who had a time worth small alone. London independent, and he launched this series called The Member Series, which the basic idea was big six, five to six hundred page anthologies on given themes, kept where the price was kept down. And I'd done a few crime ones and science fiction ones for him. And with Nick, we used to have a twice yearly lunch, where I'd sit down and I'd say, "Oh, it'd be interesting to do a book on this theme," and he'd say, "Oh, would you like to do this one?" And in fact, I'd never been into these offices, because we'd always meet in town over a Chinese meal or another meal. And I'd just read a few American books recently at the time. This was in the early, in the early 90s, I'd read a few interesting books. It was David Guy's autobiography of my body. It's a guy who wrote the book on the atomic bomb, but he also did a very, very erotic book. And there were little examples here and there, which were really interesting. And I mentioned to Nick, you know, you've done science fiction, you've done cry, you've done spy, you've done thrillers, you've done westerns, you should do an erotic one. And Nick, who is very, very, very proper and British, so the whole, no, I don't think so. Every six months for, I think, two or three meals, I went back and said, "You know, I really think you should do one." And Nick gave in, I don't know who he would. And he said, "Okay, let's do it." Standard advance, almost to get me off his back. So I did the "Man of Book of Erotico," which was the first volume. It was all reprints, but I had Perkins, I had Meltzer, I had a story by Will Selfe, I had Clive Barco, who was a good friend. And the one I wanted, I wanted to next up on the David Guy book, but he never wanted, he's never wanted it to be republished. I had Anne Rice, I mean, I had Martin Amis, who's written one or two stories here. So it was really a high quality and what I can follow, I delivered it. I mean, there's so much more I wanted to put in, but I only had six hundred pages. I delivered it to, once in publishing, and when there was like a weak silence, which was very unusual. So I rang the offices and where, which I never visited, and a lady picked up the phone, "Hello, Robinson, publishing." And I said, "Can I speak to Alex Stepp?" who was, in fact, at the time. I mean, really about twelve people in the company then. And now they've grown to nearly a hundred, one, thanks to Erotica. And Alex Stepp was the managing editor who dealt with all the manuscripts and production. And I said, "Can I speak to Alex?" And she said, "No, yes, you're speaking." I said, "It's Max and Jack Moskey." And there was sort of a strangled cough, which I thought was a bit odd. The leading question is now they're right to direct. I look quite a good friend. And I was brought through to Alex and I said, "Who was that on the switchboard?" And he said, "Oh, it's so-and-so." He said, "I was going to phone you." The manuscript has come in and, of course, automatically was photocopied. And every female employee in the company has seen it or glanced at it and they all think it's absolutely pornographic, demeaning to women that even though more than half of the authors were female. And Nick is just about to, he's been putting it off for a few days to phone you and say, "Well, we're going to spike it. Keep your beer and beer advance on the signature, but we can't do it." And he said, "Wait, wait until Nick calls you." I thought, "Well, I tried. At least I'll keep, I'll keep the advance." And the money's to the authors. We only do on publication, so at least three authors wouldn't feel that they'd been exploited. And I just wasted a bit of their time. And then two days later Nick rang me and I said, "Yes, I think I've heard of news. They know we're doing it. I'm going to have a mutiny on my hands, but at the time the book clubs were very important, both in England and America. And when the book was taken by the book of the month club, that was a big, big deal. And basically the book had been photocopied almost without people reading it and sent automatically, like every book was sent, photocopied the manuscript was sent to the British equivalent BCA book club associates, the equivalent to the book of the month club, and they'd come back with the biggest order that any book club from Robinson published had ever had, so Nick decided to publish. So the book came out, despite obviously the opposition in-house, and of course became a major bestseller. It's still in print after 18 years. The initial? Well, you've done. I think it went through 31 reprints in the first five years. Then we did an upgraded edition with a new cover, and it's still available after 18 years, and it's now done 650,000 copies between England and America. And as a result, I was asked, "Can you make it an annual?" And it's been going for 18 years, and I've even done four volumes of erotic photography, not that I've ever taken a photo in my life. It's really very again. I mean, I look at photographer's portfolio, isn't it? What I like, if I think it's good, I'll publish it. And apart from that, Robinson, who has since expanded, taken over another company, have done an erotic poetry, gay, an autaker, with other editors, not with me. And it's now, obviously, and also now doing a lot of an autaker in e-books. How has that form changed the market, as we know it? It's just expanded the market, particularly for an autaker. The problem here again is, and it's... But I think it's now 99% is actually terrible, because, of course, it's so easy to publish e-books, and to self-publish. And, of course, I mean, I still needed the mammoth book of your autaker. I mean, I've just delivered volume 12, and we did five. The first five volumes were not even numbered, so we've done 17, plus at best of the best. And, plus, I've done single theme ones, in addition to some. I've done about 25 erotic anthologies all together, but, I mean, one knows. And over the last few years, it has been so much published digitally, which is absolutely awful, and I'll see a lot of it. But usually, I know, after one or two paragraphs, whether it's worth it or not, but they are still good writers emerging here and there. I have attitudes, like market attitudes from outsiders, towards genre fiction, erotica, crime, SF. How do you think it's changed over the course of your publishing career? We see more literary writers dabbling into certain genres. Indeed. What's your perspective on that, or how do you think it's... It's something I try not to think of, basically, in so far as... I mean, it's always been important, and there's... I mean, publishing is an industry, and I mean, I worked in publishing for 22 years. And I know, I've published a lot of books, which I never had, no literary value, but obviously, you're working for a company, the company, whether you've got your part of a conglomerate or not. I mean, I worked for the Hearst Corporation, I've worked for Penguin over the years. And, basically, as a publisher, you have to accept that it is a business. And, from a business point of view, genre, not including your autocartical last year, was always an area which was solid. You don't lose much money. Publishing, crime or satisfaction, fantasy and horror or thrillers. You've got a sort of bottom level, which you know you'll make a small profit. And there is always an upside. If somebody breaks through, then you can do very well. So, it's always been generally accepted. I mean, horror has been... It's ups and it's downs, but it's always been around. The only area which I've not been involved in myself, and which has always been a very minor aspect of popular genre. - Westerns? - Yeah, Westerns. I had a literary agent down a few months ago who just said, basically, what are you looking for? Just not Westerns. Don't send me a Westerner. Westerns and sports books sort of, you could publish anything with cats, say anything about it. I mean, golf was okay, but not other sports generally. You could publish anything with Jaffa Rippur, anything with Sherlock Holmes, anything about Elvis, any gardening book. And God, did I have a published gardening and cookery books in my publishing career? It was, I used to run Good Husky Pink. The publishing side of the Good Husky Big magazine was when I was the publishing director for Hearst. So, no, I mean, popular fiction has always been fully accepted. The trends come and go, but they're always there. And that question about respectable writers jumping into genre. To me, Martin Amos' night train is incomprehensible and bizarre. I don't think... It's a pretty poor crime book. Good. I'm glad somebody who's an authority on this agrees with me, because I just went through. I'm not really sure what he's trying to do. Do you come across that? The sense of I'm a literary writer. Therefore, the genres are child's play to me. I can go in and do what I want. And yet, as we see occasionally from the faces. I think Martin Amos is in fact the exception that confirms the rule. Even though he is a fan of crime and science fiction and is reasonably knowledgeable, I mean, he was one of the first people to come out as an advocate for Jimmy Bellard's stuff in the early years when Bellard was still seen as merely a science fiction writer. But a lot of the other writers basically either understand the traditions of a genre like Margaret, I would say, or John Banville, who's now writing crime. Under a pseudonym, right? Oh, under a pseudonym, I guess. But it's an open pseudonym, didn't you? I know it. There's Benjamin Black, but of course, I think it even said on the first book, but John Banville writing as Benjamin Hammack, because of course they wanted to get her piece of audience. So it's not a bad thing. Sometimes they fail a bit, but sometimes basically they really come up with interesting things. And somebody like John, and then it works the other way around. Somebody like Michael Schaben is writing good popular fiction. I mean he's written a small, was it a fantasy epic? It wasn't an epic, it was a short book, was it Companions of the Road, which in that world is dedicated to Fritz Lieber and Mike Morkock, and the Yiddish policeman's union is a wonderful crime book. And then you've got somebody like Jonathan Latham, who comes from the science fiction area, who's now breaking out of it and moving into the mainstream. So it works both ways. I mean, it's thousands of people have mentioned it, but the three-odd William Goldman, nobody knows anything. And it continues to stay, that we're new people coming into genre, from outside of genre, and people coming from genre into the mainstream all the time. How much does your history within the publishing industry affect your writing? Not the contracted erotica writing, but when you feel creative, when you feel a novel coming on, how much of that is it tempered or affected in some way? I've worked in publishing, I know this isn't going to sell, or... I've always written exactly what I wanted to write, until recently, where it wasn't offered, which couldn't be refused, but I'm now having fun with it. Basically, the first novel when we delivered it, we were assigned a line editor. I mean, it was commissioned by the publishing director of the company of one of the large conglomerates. But then, of course, when it came in, it was given to one of his senior editors, who is a very nice lady, but didn't quite understand what we were doing. Too many juices, little things here and there. We had this running battle with her on the first volume, and lots of things she wanted out. We managed to salvage about three quarters, and we made a few compromises in there. And then, on volume two, we kept on adding more, so that we knew we could take average it down. And then, on volume three onwards, because the books were doing so well, she's saying, "Can't you add a bit here, there?" It's always been a running joke between my collaborator and I, where we, occasionally, put in the line, knowing that Jemima will say, "Oh, this is not very romantic." So, they have been found. And, in fact, the sixth volume, in fact, which will be coming out in September in the UK and in Germany, moves into a new area. We're keeping obviously all the sexual elements of the previous books, but the book now is almost moving into fantasy areas, because that's where we feel that it was to go now as shot its bold. It is going to come back to a high level of any was before, but it's not going to go back to down there. Getting any vampires in this? Vampire is a big? No. Okay, that's a vampire thing. It's completely gone now. So, now we've got a brand, as publishers. We're trying to broaden the band and making much more general is moving into Hillary Mantell, Kate Moss type of historical, Eren Morgan Stunzer of the Night Circus, Angela Carter, Taylor Toot, which is, we're trying to keep our readership by expand the brand with the next book. At which stage, in fact, it's very possible that the publishers will actually then reveal who are the authors if we can break out into a much larger market without losing, obviously, our wonderful mummies who buy the books in super markets. Any blowback from your kids over the course of dad's dirty old man or anything? My children have never read my books. I think quite deliberately, I mean, my son has probably possibly read some of my science fiction, but I think they'd rather not know something you want with these children, they want to know what their parents are up to, left, left, left, left, left, right about. Dream Project? Not all that you've worked on if you had the time and space? Well, there was one book I was going to start last May and then I've got a sideline and I've written another six cents. Now, in fact, having delivered number six of this particular series, our agent has agreed with publishers, and even though, particularly for German publishers, almost begging us to do that in laboratory the dream that if we do, it wouldn't be until next year, and then we don't know what it would be about. So I intend, basically, to go back to something this, well, from next month, I'm still enjoying, sorry, the break for a few weeks, then at the end of June, my wife and I are going to be in your notion for a long period on almost semi-desertile and overall at my laptop, and I'll see whether I begin. I've got one or two ideas. I mean, there are two books that I've had in mind for over 10 years, and every time I start a new book, I decide not quite ready, I'll do something else. And purely because they're both so could be different, I want to do a final science fiction law. I want to do a time travel. A time travel love story. One of my favorite books in science fiction is, it's awfully written, but I think it's a wonderful book, and I dare not reread it. I probably haven't read it for 30 years now, but it left a great impression, and I want to do something of that. I woke up and I said, I don't want to reread it. It's Isaac, as it was, the end of eternity. And it opens a lot of possibilities, but he's such a bad writer, unfortunately. So, it's a sort of Romeo and Juliet time travel story that I'd like to write, and I said, I feel that I owe it to my own youth, and my love for science fiction, I do want to write one more science fiction novel. Even though, of course, as an ex-publisher, I know that you must never move from genre to genre, but even before, this is what it's a series, I've always been in the rather invidious position of not having to write for the money. I had a career in publishing my father. After my father's death, I came into quite a bit of money, so I write basically what I want to write, and the other one is a semi-historical book about English and American expatriates in Paris in the early 1950s, which is a period that's not really been written about. You've got, obviously, all the novels value in the 30s. Oh, hello, Gertrude. Hello, Mr Hemingway. Hello, Scott. But nobody has really written much about Paris. French authors have a bit, but of course, they've been concentrating on the French characters with maybe one or two fallen characters, because this is the era when so many American jazz musicians were playing in Paris, Charlie Parker, and others. It also, when existentialism was beginning to break in France, Camus was still alive, Sartre was still around, and I was brought up in France. Obviously, I was brought up later in France. I wasn't there during that period, but if I was at the tail end of it, I was still much too young to know what was going on about that. So a period that fascinates me. So I wanted to be about English and American expatriates in Paris, and this would be a purely humane student of all, and maybe now I'll, but ask me again in seven or eight weeks when I've stopped, when I get on to interview you notion, and I open my laptop one morning, and do you have rituals? Do you have anything you can talk about? Yes. Unlike my good friend Michael Morkock, who, when he used to write, he's now, he's, he can't do it anymore, used to write with a bottle of bourbon or whiskey, and managed to do a fantasy novel in about three or four days. I think all writers have their habits. Mine is when I start a book, basically, I'm relentless. I write every day. I get up at 6.30 every morning, and I write up 12. Sometimes writing becomes out of it is awful, and has to be rewritten or dropped totally. But I can only write in the morning. And I always write with loud music, with vocals or without, with vocals. I don't follow, I'm incapable of writing anything when there's words floating in the air. And it's always rock and roll. Interesting. That's a good lesson to do it. Of course, this would also. Not fiction, if I'm doing reviews or articles that I can't have music, but for fiction I need music. Besides this Asimov book, what other touchstone books have you had, and are there books that you go back to from your, your youth? Not really. I tend, I think I'm scared to get back to them. And I mean, I get about 30 books in the post every week on publishers, because I review, I used to, for 10 years I had a column in Timeout in London. And then I was convinced to move away from Timeout and move to the Guardian. So I did another 12 years as I did 22 years of monthly columns. Now I do much less. And although I've agreed now to do a sort of, not so much a column, but my book of the month plus two or three recommendations for the British website, lovereading.co.com, which I'll be starting again in July. I've done the occasional one-offs for them, but I've now agreed purely because I feel guilty publishers sending me so much stuff and not having, out of maybe 400 books in the last year of only having reviewed five or six as an ex-publisher, I feel guilty. So, but these will not be extensive reviews about from the book of the month. But no, I mean, they have books from my youth that have left, obviously a lasting impression for the Scott Fitzgerald is still, I mean, I did my PhD on Fitzgerald. Well, it's not just on Fitzgerald, but it was basically on aspects of despair in contemporary literature. I did a comparative literature. So I had Scott Fitzgerald in America, Cheshire de Pavezi in Italy, and a lesser-known French writer called Pierre the Yolo O'Shele, who's best remembered in Europe these days for a book called "The Fulfillate Will of the Wisp," which was filmed by Louis Malle, a story about a man who spends his last day trying to see all these friends before he commits suicide, Pavezi committed suicide. French-level drank himself today. It was a very cheerful experience. So, but French-level is somebody who did leave a lasting impression long before he came back into fashion. There's something wonderful about Fitzgerald. I mean, I like the romantic writer. I like it or not, which is why my whatical, in fact, has always been a bit different from other people. I mean, even though at times one set of one of my books, when I was now the king of the whatical thriller, which of course, published, would be putting on the back of every book ever since, if I do a children's book, is by the king of the erotic thriller, not that I ever will do a children's book, but I would say that quite a few of the books I would have done. And in fact, I wrote one called "Confessions of a Romantic Pornographer," which basically defines the sort of... the sort of eroticism that I was trying to write, eroticism that we're feelings, very explicit that we're feelings. I think the emotions are what interest me more in a whatical rather than the actual hydraulics and the sex. So, it's got Fitzgerald, obviously, Bavese, Andrew L. Rochelle, because he looks like I've read extensively. A period, a well-known French writer called Ahaigon. We wrote an erotic book called "I Means Come" when he was still young, but he had a period. In his 60s, we wrote three or four, absolutely incredible novels. Not all of them have been translated into English. J. G. Bellard is a major influence. I love John Irving, sort of. Even when John Irving is just bringing up bears and wrestling and going over the same grounds all over again, but I think there's still something magical in what he does. And who are you reading now? Right now, I'm reading the new list on the carry. And then... Any good? I'm halfway through. It's good to stand up at the carry, I would like to have a carry. I do like Spythmillers, in fact. Over the last few years, I think I've enjoyed more Spythmillers, I swillers, more than many crime books, purely because I said I've had 22 years of reading so much crime. Over this year and next year, I'm also a judge for the Crime Light Association, the Kreecy Dagger, which is one of the first novels I've been doing in a lot of first novels this year. But Spythmillers, I mean, I'm a great fan of Charles McCarry, Robert Littel. So it's very, really very diverse influences. Science fiction basically, I mean, a lot of authors I like, and one of them died today, Jack Prince died today. I mean, he was quite elderly, so it's not, obviously. A major surprise in crime, a great fan of Don Westlake and many others. The problem in crime is, I'm part of the crime community and I'm friendly with so many people. I forget to name it. I'd rather not mention anybody who's alive. I mean, amongst dead people, I'm Westlake. It was a very good friend. I do enjoy it. But my favorite crime writer, in fact, is Corneham Woolwich, who also wrote as William Irish. Many of these books were filmed. I married a dead man, night has a thousand eyes, dried well black, well all. And, of course, people I published when I finally started publishing crime, Jim Thompson, David Goodes, Boris McCoy, Jim Schuen, I think it's a very underrated crime writer. So it's a very, very mixed bag of tastes and influences, but I still read a lot. I mean, I read very little not fiction, but I read a lot outside genre too. Looking forward to you on the top, which will be coming out to you. Oh, really? Oh, that's where you're here. I'm sure a way to pick up an identity. I don't think I'll be giving that one away. Somehow. And never read their second book. Any good? I liked it. I loved the first one of the secret histories. Admittedly, because I went to a small liberal arts school in Western Massachusetts and then a classics-oriented grad school, which sort of was right up my alley. Last question, a perspective on American readers versus UK, or in comparison to UK. Do you have any broader takes on what the audiences are like, what they're, what you look for as a publisher, regarding either of those questions? As a publisher and as a reader and a fan, I'm somehow much more open to American writing, but I'm to British writing. I find a lot of British writing fairly insular. But and French writing is even more insular, although they are some wonderful French contemporary writers. I've read quite a lot recently by a French writer called Patrick Modiano, who's who's had a few books translated, but who is very much in the Fitzgerald, by his introduction, and he's fairly big in Europe. But in terms of the readers and the tastes, I don't know. But obviously my books, I mean, my own writing, as opposed to my editing, has never sold huge quantities of America. I sell more in the UK. I sell very well in Italy. Until recently, I didn't sell a talk in Germany now. Now it's become, now I'm the Bertelsmann author of the year. So, not really. I mean, I don't know, basically. I forgot my real last question. You attend a lot of book fairs. I only cover pharmaceutical trade events like the American Association of Farmers Scientists, which is probably not as interesting. Any trade show advice to give to listeners? All I've got is your business cards in the left pocket, the other guys' cards are in the right pocket. We're old, comfortable shoes. Okay. Maxim Jakobowski, thanks so much for your time. Thank you. And that was Maxim Jakobowski. You can find his website at Maxim Jakobowski.co.uk. And I hope you'll bear with me on this. It's M-A-X-I-M-J-A-K-U-B-O-W-S-K-I, just like it sounds. Maxim Jakobowski. When you're there, you can find links to his books, reviews, anthologies, and, well, everything else he's involved in. As you can tell from this episode, he's really got a lot to talk about when it comes to publishing and all different types of fiction. And that was the Virtual Memories Show, your weekly podcast about books and life. Come back next week for a conversation with Lisa Borders, author of the new novel, The 51st State. We'll talk about whether South Jersey should secede from New Jersey and how it'll prevent an invasion by Delaware and Pennsylvania once it secedes. In the meantime, go visit iTunes and subscribe to the Virtual Memories Show and leave a review. And you can visit chimeraabsgira.com/vm to find past episodes and make a donation to this ad-free podcast. Until next time, I'm Gil Roth, and you are awesome. Keep it that way. [Music] [BLANK_AUDIO]