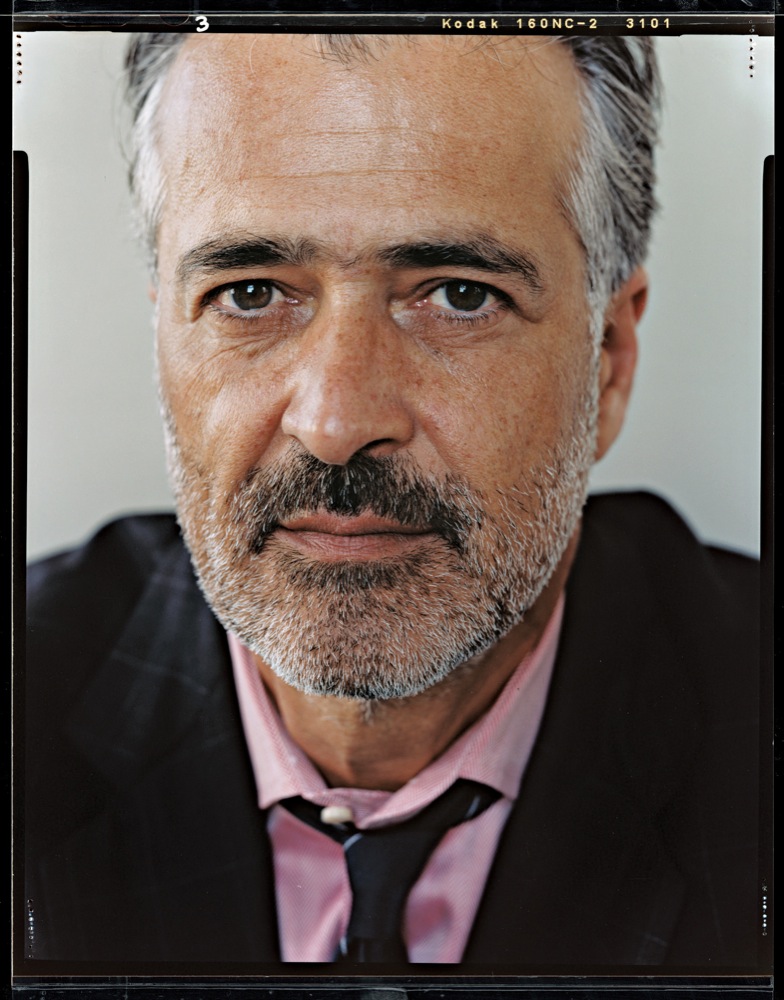

Hooman Majd joins us to talk about his new book, The Ministry of Guidance Invites You to Not Stay: An American Family in Iran, documenting his family's year-long stay in Teheran in 2011. We also cover Iran's conflict of nationalism and religion, its nuclear issue, the possibility of becoming a modern state without liberal democracy, why Israel and Iran should be BFFs, whether there's a word in Farsi for 'sprezzatura', and more!

The Virtual Memories Show

Season 3, Episode 25 - The Land of the Big Sulk