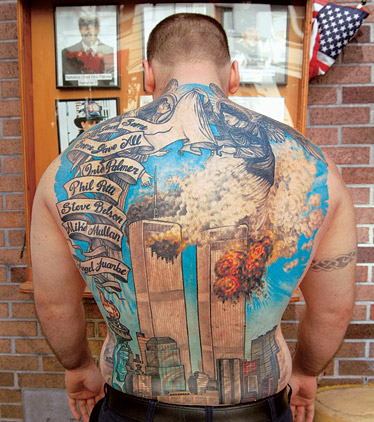

[music] Welcome to The Virtual Memories Show. I'm your host Gil Roth and you are listening to a podcast about books and life, not necessarily in that order. This is the first part of our 9/11 special. There'll be a second episode next week featuring a conversation with author and law professor Thane Rosenbaum about his new book Payback, The Case for Revenge. But this time around, we have a conversation with Jonathan Hyman, a photographer who undertook a 10-year project to document the murals, tattoos, and other memorials to the September 11th attacks. In fact, I met Jonathan when a mutual friend told him about my very modest 9/11 tattoo. I say very modest because one of his signature photos is of a fireman who has this absolutely enormous back tattoo about the attacks, complete with a blue sky. It's really quite a spectacle. I have a couple of words on my arm and that's it. University of Texas Press recently published The Landscapes of 9/11, A Photographer's Journey, which is a collection of critical essays about Jonathan's work. It's a pretty fascinating book, but you'll learn more about it from our conversation. Speaking of, I have to apologize for the sound quality a little for this one. We were recording in Jonathan's studio and I used some floor-mounted mic stands as opposed to the table-mounted ones or the handheld mic I normally use. I didn't position his too well, so there's a lot of plosive sounds on the P's and B's. I killed some of the bass to try to make those a little less obtrusive, but you'll have to suffer. If you want better production quality, I guess maybe you could pay me to hire an engineer, but I didn't think that was going to happen. Anyway, Jonathan did have a few things he emailed me about after our conversation, just to make sure I include him in this introduction. First, he wanted me to mention that the University of Texas Press website has the book's introduction by Professor Edwin Linenthal up for reading, and he also wanted me to mention a couple of essays that he didn't get around to talking about during our conversation. First one is by Jan Ramirez, who is the head curator and chief of collections at the National September 11th Memorial and Museum, and in the essay she tells her story and that of the museum and how it came to exhibit and not exhibit certain objects and other materials, and ties the museum's identity into Jonathan's collection and the board's interest in and their use of it. Also, Charles Brock from the National Gallery in Washington ties Jonathan's work into American cultural history by comparing his photos to others who've done massive projects with the size and duration of this one. He also argues that Jonathan has documented a femoral and under-appreciated germination of source material for artists whose work will be canonized, I guess, in museums like this. Now, Jonathan Hyman kicking off the virtual memory show 9/11 Special. It's my guest on the virtual memory show today is Jonathan Hyman, author and photographer and artist and a lot of other things. He has a new book out, well, he's a contributor to a new book, The Landscapes of 9/11, a photographer's journey. He is, in fact, the photographer undergoing that journey. Jonathan, thanks for coming on the show. Thanks for having me, Gil. Why don't we start talking about landscapes of 9/11. Tell me about the origins of the book. Well, the book is really a combination of many things that happened to me, for me, with me over the course of the very intensive 10 years that I spent documenting the folk art that people made in response to the September 11 attacks. I started taking these pictures as a result of my interest in my area of personal and professional expertise, interest in things by the side of the road. So, I noticed very early on that it looked like there was some kind of a public conversation going on beginning the day of the attacks. I set out to start taking pictures originally just to use for some of the collage work that I was doing as a fine artist, in addition to some of the more documentary-style work I was doing as a photographer. And so the book really explores all of the various genres, in fact, that people created and participated in everything from full-body back tattoos with the towers exploding and being depicted on a fireman's back to very tiny little crosses drawn on somebody's car. It's interesting that I do have a landscape being both the body and the environment around us. How difficult was it to approach people to ask them to shoot either the tattoos or the murals they were painting in their buildings? Well, this is an interesting question because some people approached me when they found out what I was doing. Other people were very reluctant to speak to me, let alone even have me identify them as someone who was making 9/11 response art. So I came up with a number of different strategies to convince people that I was okay, that they could trust me. And I did that by doing a lot of listening and by also promising every person that I took a picture of, whether it was their tattoo or their car or their house, that I would give them a print, at the very least, as I got into digital photography, send them a jpeg for their use on their computer. And I was exceedingly conscientious about this. I did my very, very best to follow through on that pledge because it's in fact what really established my reputation as someone that people could lead into their life. Especially at a time like that that was so fraught with fear, it can be kind of worrisome to have some guys showing up and I'd like to take a picture of… Well, fraught with fear is putting it nicely actually. That's a nice way to say it. The truth is… The truth is, this was a very complicated time, a very dark time actually. And I'll be honest, everybody was jumpy. That's the word that I feel most comfortable using. And in fact, one of the things that was interesting and I talk a little bit about this in the book. As you know, there are a number of essays in the book written by scholars and museum professionals, but I was asked as co-editor of the book and as the photographer to also sort of provide a narrative of my experience. And one of the things that I talk about in the book is my experience in navigating and negotiating along the way. And I can tell you that I spent the majority of my time within a hundred mile radius of New York City. I guess maybe the words paradoxically, as I got further away from New York City within that hundred mile radius, people were a little more cautious and a little more distrustful and a little more reluctant to talk to me and to be photographed. The further I got from New York… Interesting. What do you think that is? My immediate theory would be that people closer to New York felt a sort of kinship or bond to everybody else around that time and maybe the further you get away from it, the more abstract it seems. So what do you think that was? Well, two reasons. Number one, one of the things that I talk about in my essay is this notion of interconnectivity. And the idea is that people are connected to each other, through family, through the fire department, the police department, EMS, through somebody who they knew who worked in the building. I can't tell you, and it's hundreds and hundreds of people that I met who directly knew somebody or were related to somebody who died in the towers. And so there's this sense of interconnectivity so that people knew everybody in general. You know, I say that in general terms. But also, but as they say, New York's a big town. And so that hundred mile radius gets absorbed pretty quickly. And also I think, you know, the truth is New Yorkers are New Yorkers in a certain kind of way, and there's a certain kind of toughness and resiliency there. I think out of collective self-preservation that life had to go on, they had jobs to go to and things to do, that they probably spent the better part of their time going about their daily lives. I can tell you that a number of times upstate New York and parts of Pennsylvania, I was almost arrested or had cameras hit with bats and all kinds of interesting, crazy things happening because people really took to heart in a different kind of way this newfound sense of vulnerability, this new sense of, we've never had this happen before, right? We were attacked, and the attack itself was kind of, you know, some sort of cultural cognitive dissonance, you know, in a certain way. But this isn't happening, you know. So I think that New Yorkers handled it differently, a little differently, not for better or for worse, but differently. So that would account for that. And so people were, you know, as you get further away from the city, I would say more jumpy. I took a picture in my local supermarket, my local shop right, and it was a picture of a cheesecake, and the box had the pictures of the towers on it. And they called the police on me, because I was taking pictures of frozen food in a eye. On authorized pictures of. On authorized pictures in a supermarket. And same thing happened in a Walmart, there was a beautiful handmade flag, beautiful, enormous hand crocheted flag done by a group of families in honor as a memorial to those who died in the attacks. And I was photographing in a Walmart, and all hell broke loose. So this was, again, back to the point of, this was a very dark, complicated time where there was this newfound collective sense of vulnerability, no question about it. So I talk about that narrative from the beginning, when I started taking the pictures, why I started taking them, how I came to see the pictures and this public conversation, and my role in it, because the minute I started getting involved in this interconnectivity, I was connecting people to memorials, in fact. And I had to be very careful to get outside of this thing, so it wouldn't affect my work because I've tried to be, and present, tried to be as unbiased as I can in my own opinions about what I think was going on in our country or what the response was politically and culturally to the attacks. But there are a lot of interesting things going on, and my notion of what I was changed a little over time and everything. But I talk about that progress over time as I began to take the pictures till towards the end of the ten-year time period when I was doing it. Can you tell me a bit about the range of expression within the murals? Well, I should say that the book approaches the murals in a very significant way. I talk about the murals, Philip Hopper talks about murals in the Palestinian West Bank, and right around near Bethlehem in the separation wall near Jerusalem. Chris D. Gruber talks about murals made in Iran in memory of those who died in Iran, in the Iran or Iraq War, Jan Ramirez, who's the curator of the National 9/11 Museum downtown at Ground Zero, talks about it. We approach it. We make cross-cultural comparisons. We make comparisons to murals within the United States, and the people who have the most to say about that are actually the only people who really don't talk about any particular photograph in the book. And that's Harriman and Lukatus. They're a team that write together about iconography and rhetoric. That's what they're known for. They took an interesting approach to this, and I didn't necessarily agree, so I'm going to answer your question by contrasting my sense of the murals and theirs. They look at the murals, and they talk about them in a way in which Americans have expressed themselves in response to this attack as a kind of a lacking of culture on the part of American and part of Americans, and sort of a way to show that this was a language of inarticulateness, like what -- is that -- their basic premise in a certain way was, is this all we have to offer? I mean, this all we can say is, God bless America, United We Stand, and how many more angry eagles and flags can we look at? And they basically said -- well, they did say that the response -- the American response to the attacks was this language of inarticulateness, and the response ran from A to B from anger to revenge. And I took objection with that and ended up adding on to my essay, and to say that, you know, that there is something going on here. And, in fact, if you look at the folk art response, the vernacular response, the 9/11 attacks, and you look at it in the same way you would look at an art movement, like impressionism or abstract expressionism or, say, Renaissance art, there are certain unique characteristics to these movements. And if you view what I photographed and documented in the same way, you'll see within a very limited range of iconography and colors and content and verbal phrases, that there is actually a wide variety of responses. For instance, there's a mural I photographed that's got a picture of Big Bird of all things, you know, with a cracked heart, and the World Trade Center towers are in the background, but Big Bird is standing in front of pink towers. Okay, and all that pink connotes in our particular time and place, and in the background, on the other side of Big Bird, is a butterfly capable of metamorphosis. So there are all kinds of interesting cues, clues, and metaphors and references that if you look carefully or there. So one of the things I did was in my essay, I talked about a particular mural downtown on the Lower East Side that had, it was an enormous mural, very beautifully done. And it had the towers, the World Trade Center towers, but they were in the shape of the towers, but colored in as flower power towers, which was a direct reference to kind of a subculture of the anti-Vietnam war movement in the late 60s and early 70s, called the flower power movement. So not only was this a call for peace, clearly not anger and revenge, but it was a direct reference to American cultural history. And if you ask me, I think that's pretty smart, you know, I mean, so this notion that it was just in articulateness and unsophisticated, you could make the argument that maybe some of it was, or you could make the argument that most of it was. One could make that argument, I won't, but they did. But I objected. So in my piece, that's the thing that we're hoping that this book will do, which is to provide a dialogue so people can say a Heimann doesn't know what he's talking about, or Harriman and Lucatus are wrong, Heimann's right, or neither are right, whatever. But the point is, is that this is a book that features these essays along with the pictures so that there's a kind of melding of the visual culture of 9/11, and still placing my work, because the work in the book is, the discussion in the book is about my work. In other words, everyone who writes in the book writes about my work, but what we're trying to do is place my work and the collection I put together in the context of both American cultural history and international memorial practice. What has the reception been like overseas for your work? Pretty good. I can say that, you know, from direct experience that you can have conversations in Europe about 9/11, about the folk art of 9/11, pretty much anything relating to 9/11 and American culture that you can't have in the United States. How so? How so? Well, that's not to say that the conversation is always scintillating or it's necessarily something that I always agree with, but the Europeans are not so supportive, I would say, of, they were not supportive of the Iraq War as a response to 9/11, so the Iraq War started in 2003, I was there five years later, and things were not going well at that time as I recall in the war, that is, you know, and do you know when I was in Austria, I saw more, I saw at least three or four more, three or four times more American flags in Austria being flown in the Austrian flag, and so one of the things that Europeans said to me in four countries I visited and lectured in, I was in Germany, Austria, the Czech Republic and Croatia, and everywhere, in each country at least once somebody said to me, in public, you know, when they were asking questions about after I'd made a presentation or give an lecture, what's with you Americans in your flag? And you know, it's a question, it's a question that could be answered in many different ways, I'm not an expert on the American flag nor am I a sociologist or a cultural anthropologist for that matter, but it's clear from hearing them, Europeans talk about it, we definitely have a different relationship with our flag. Now one of the other things that Europeans would ask me was, what is it, what is it, what is it, what is it, what, why would anybody do this to themselves, why would somebody put a full back tattoo on their back that cost them $5,000, what is the point of that, you know, why do you do that, and I would say, well, here's what he told me, this is the guy who told me, even he thinks tattoos are vulgar, but this attack was so deeply personal to him, so, and the loss he suffered on a personal level of some of his best friends, and he said he had no choice, and I told him that heretofore I'd never heard this kind of things coming from Americans, and I think that, you know, that's an interesting thing for me, and one of the things I also reminded Europeans is that we don't have any practice in this, you know, this is new to us. We don't have wars going on in our country, we don't know from World War I or World War II or, you know, and these wars weren't fought on our territory and so on and so forth. And so they said to me, well, that's true, that's, and so at one point I spoke to a guy who, in Zagreb, Croatia, who said, we do, we're good at this, we know how to do it, and he showed me a number of examples of memorials that were, you know, erected after World War II, and he showed me some memorials that were erected after the Balkan, the meltdown of Yugoslavia, you know, with the separation of all of the Yugoslavian states, and he said, but usually, you know, unlike you Americans, we like to wait for an immediate gratification culture, right? I don't know. Well, he said, we don't necessarily make a memorial, we wait 20 or 30 years, we wait. And by the way, that's been one of the arguments of some people from certain places in academic life, and I would say in American contemporary culture that when people complain it's 12 years, we still don't have a museum or it took X amount of years for that memorial to be built, many people have said, I'm not one of them, and I stay out of these things, you know, many people have said, what's the rush? Yeah. And the answer is, the rush is, I would, you know, people argue is that the families who lost loved ones need a place to go, and then the response sometimes is, well, can't they find their own place, you know, that's not my response. But so there's this, there are any number of running dialogues, I guess is my point, and the running dialogue in Europe is an interesting one because I was told over and over again, you had us, you really had us, we really, we were on your side, we were really with you, and you know, as it turns out, one of the things that has affected me in a personal way and a professional way, I don't say this lightly, I mean this, I mean this seriously, these attacks were so profound and so different and so awe-inspiring in one way, and so terrifying, and I talked a little bit about this new sense of vulnerability in other ways, that I've encountered a number of different people and different walks of my life who, it turns out, hate George Bush more than they hate war, and so that affects the way you would look at American contemporary culture, it affects the way you would look at people who get tattoos, that memorialized people who died, that you otherwise wouldn't pass judgment on, and it took me a while to realize that, and I had a little mini epiphany when I was in Graz, Austria, and I turned the corner, and there was a dumpster down this dark alley, and I got closer and I saw this yellow dot, and I realized as I got closer, it was a picture of George Bush, as Mickey Mouse, he had a Mickey Mouse hat on, and I can't remember, if it was a stencil, but I can't remember if there were any words there or not, I have the photo somewhere, and I said that's it, George, they turned George Bush into Mickey Mouse, and so there's a lot going on there, and many people, even people who came to dislike and George Bush and the response in the end that he made militarily, even in the beginning, people were giving him credit for his leadership, I mean, everything changed so much. Now you remember how we turned on Giuliani, all of a sudden he was the great mayor when he was not held in particularly high esteem for a while leading up to the attacks, all of a sudden he was America's mayor, and we, you know, our opinions changed, and then like the ancient Romans, he decided he was going to, maybe I need a third term in office, and that's when the public opinion started to waver, but, you know, that moment of crisis, some guys either shine or we want them to shine, I think. Agreed, I'll let you stick to the analysis of Giuliani's leadership, but anyway, my point about all of this is, relates back full circle, I hope in some way, to this question about the Europeans and the difference and everything, so some ways we're very different, and other ways we shared things, part of our culture did anyway, and I think, you know, who knows what would have happened, how things would have turned out if we didn't go into Iraq, but one of the things that I had to do, by the way, early on in this ten-year process was try to sort out and separate responses that I felt were not necessarily tangentially connected enough to the attacks if they were Iraq war kinds of visual responses or iconography. I tried to say very focused on 9/11 related stuff, although I photographed a lot of interesting things along the way relating to war and the Iraq war in Afghanistan, certainly that's stuff that I was a material I was interested in, but I don't consider that part of my 9/11 archive, unless it's got some, you know, meaningful connection, at least to somebody or to me, you know, because that can get complicated when you try to throw too many things into the mix. Yes, as we learned. If you talk about the sense of time that the Europeans have, in terms of letting things settle before doing these monuments, you went back ten years later to many of us. Any of the mural sites to reshoot them, what was that process like? What did you learn over time like that, the decade in between? Well, I was incredibly persistent and it wasn't just that I went back on a ten-year anniversary. I decided on the ten-year anniversary I would refotograph 300 places that I'd already been in the first nine years and 11 months. So I did that and sometimes it was visiting a person who got a tattoo. Sometimes very often it was a mural or a public space, but you should know that, and I have pictures like this in the book, it's not just on the ten-year anniversary, but particular objects or people or public art in the form of murals or a sculpture that interested me in some personal way, I would repeatedly revisit sometimes once a month, sometimes every other year, sometimes every few years. And so a lot of different things would turn up, neighborhoods would change, buildings would disappear, and that's one of the things that Harriman and Lucas talked about in their essay is that it shows that one of the things they talk about is the not just our culture, but they point out that everywhere I took, well not everywhere, but most of the places I took pictures, there's barbed wire, broken windows, blight as you might say, right. And my response to that, by the way, isn't necessarily that we have an infrastructure in our country that's failing per se, that's not just, I mean clearly we have issues with our bridges and things like that, but the point is that when you make a mural you need a lot of space, and if you're in a vibrant neighborhood that space is going to be covered by advertising. So sometimes neighborhoods would be reborn and the murals would go, sometimes in certain neighborhoods like Marine Park and Brooklyn, the murals are testidiously and carefully watched and kept up, you know, guys go, one guy in particular who's I feature in the book and my narrative, Joe Indart, he stays on top of his murals, and in fact he looked out for me and I looked out for him, in fact, he introduced me a number of police officers and firemen and New York City workers so that I could shoot their tattoos. He took me to their private beach club out on Breezy Point, and one time I was revisiting one of his murals in Bensonhurst and somebody had written across an American flag where there was a staring, angry looking eagle, and I should backtrack and say, a year earlier, I took a picture of a Muslim woman with her head bowed, it's a color picture in the book, her head bowed walking past, I didn't set out to do this but the way I've captured this moment, the eagle is staring her down, so I was really surprised on one level and not so surprised on another level that a year later somebody had written across the American flag, fuck all the injustice and they had put scars on the eagle's face, painted on scars, so I told him about that and he went the next day, he threw a fit and then went the next day and fixed it, but on the 10 year anniversary there's some interesting things that happen because right around the 10 year anniversary as you know a little bit before the Navy SEALs killed Bin Laden, and what I noticed is that most of the murals remain fairly static, they were not upgraded or updated to take into account contemporary American political culture or contemporary American culture in general, things did change but the ones that remained the same, in other words if a mural was a 9/11 mural and it stayed a 9/11 mural over 10 years, it might have been touched up once or twice but the content, the iconography, if there are any verbal phrases, they all stayed the same like, almost like time pieces in a certain kind of way. There are other murals for instance in Queens where a guy who was a Muslim carpet store owner had a muralist come and I call it an inclusive mural, it had the Muslim crescent, the Jewish star and the Christian cross and it was essentially, why don't we all get a long kind of mural, it was a nice mural, it picked people in the neighborhood, had a nice American flag and it didn't say God bless America or united, it's united we stand, it actually said we stand united, you see, and I've done so much analysis of the verbal and pictorial language of this kind of language to emerge from the attacks, both verbal as you say, and pictorial, that to me that was meaningful. So what happens is a year into the Iraq war, I think this guy who was the proprietor of this business feeling a little better about being in that neighborhood and being Muslim, he allowed the muralist who was always using that wall for many years as what's called a permission wall, it's his wall to work on with his crew, he allowed him back permission to do what he wanted, and what did he do, he changed the mural and it became a mural, and we have this in the book, these comparisons, he did a mural depicting King Kong when the new King Kong mural, a movie came out, in that sense it recognized American cult, popular culture and contemporary culture, but not in a meaningful way having to do with the contemporary language and culture around the attacks. So on the 10 year anniversary, this guy I mentioned Joe Indart, but in May I guess or June, early June, a couple of months before the attacks had the 10 year anniversary, after bin Laden was killed, he went to a mural that he had done, a fairly generic 9/11 mural, but it did have the names of a number of people who died on the mural, he always put them on a scroll, and he did that when I asked him, as I suspected, because he wanted to have a religious content and he used a scroll as a metaphor for that. He had a mural that was fairly generic as I say, and the mural said, it was a very, very large bald eagle, he was a big eagle painter in Indart, but it was also a very big beautiful, he did flags wonderfully, just painted the flag better than anybody I've seen. So he had, above the flag he had the phrase with liberty and justice for all, and the day after bin Laden was killed or shortly after, he went back and painted on the mural and we got it, referring to justice. So there were a few things like that that changed over time, but for the most part, murals disappeared because the buildings and the walls they were painted on, were either painted over or wrecked, buildings were just, buildings disappeared, or murals stayed the same and they were kept up in certain neighborhoods, not many. And then lastly, some were like in Marine Park, where Joe Indart did many murals, they were fastidiously guarded and kept up. Now how did you change throughout this process? You assume I did? Well, you mentioned some possibility of changing the beginning. I'm kidding. Well, I can tell you this, I've heard so many different people tell me their story, their narrative. On a very simple level, I've become a really, a much better listener. And not only am I a much better listener, and I'm going to exaggerate a little bit. But I've heard so many people so passionately tell me their stories with such belief, and as I say, passion, that if someone came to me and said to me, "Marshans came and we have evidence of this," and they actually put missiles into the Pentagon and the World Trade Center Towers, I might be able to say, "You know what, okay, and you could tell me something in the other direction, something very conspiratorial or something like that." And I would say, "You know what, I'm going to go home tonight, and I'm going to noodle around on the internet, and I'm going to see if what you're saying has any credence at all." So I guess my point really is that I used to write people off a little faster than I do now. And I've come to believe that there's something to people telling their story. And I guess that- Yeah. Not necessarily the fact but what they're trying to convey about themselves. Right. And that's right. I couldn't have said it better. So that's right. And so what that allows me to do, though, is to take a step back and do something that I never did before I began this project. I will be able to look at a picture of that person I took of them, I'll be able to look at some artwork that they may have made or a tattoo on their body. And I will be able to consider what they told me as inextricably connected to my experience of having met them and photographed them or the object they made. And it changes what I believe about them. How did you get started in photography? I've thought about this a lot because I went to graduate school at 27. I'd been out of college five years, I was a serious artist, had a studio in New York. I had a gallery that was selling some of my paintings. I was a person who you might say, I was beginning to have a career. I was selling anywhere from, depending on the year, eight to $15,000 in paintings. But I had to support myself doing something else. But I was becoming, you know, I was on my way. Who knows what would have happened. But I went to graduate school. And at the time when I went, I was a pretty good abstract painter. And over time, I started to think a little bit differently about painting. And now on a backtrack, I can tell you that while all of this is going on, from a very early age, not only was I interested in art, my mother has told me she recently read some diary entries of hers from 1968 where it's a rainy day and I'm copying Mondrian paintings out of a Janssen art history book. Always interested in art, but she bought me a camera, a little Kodak camera, with that cartridge, those little roll cartridges, I forget what they were called, I don't know if it was a 110 cartridge, I don't remember, but she bought me a camera for my 10th birthday. And I always had an interest in taking pictures, but I never considered it art. When I was younger, it was just something I did. My father had a Zeiss camera, I noodled around with it, but couldn't be bothered with having to focus it, it was hard to focus. And I took art classes in high school, I had pretty good careers in art in high school, such as it was. But my senior year in high school, I had a girlfriend who was a pretty good photographer. And she had a manual Pentax K1000 and it turns out that I was more interested in that camera than she was and she gave it to me to use. So I began taking pictures seriously in 17, 18 years old and I've got some great stuff over the years that I've been digging out of my studio, I was fortunate that I've saved some stuff, like even when I was in college, I went to visit my grandmother who, as many people from where I'm from, do, had a grandmother living in Miami Beach. And I photographed South Beach before it had its rebirth. I have some incredible pictures that I took, that'll be worth something to somebody someday. But anyway, I took a photography in college, took classes, I was in a number of exhibitions, I printed my own stuff, although the best thing about digital is I didn't have to print and develop my own stuff anymore, I never liked it. I was only marginally good at that, I was good at taking the pictures. I went through Europe after I graduated college and shot probably 5,000 slides, I bought myself my first camera, I bought a 50mm lens, it was a conica with a really good 50mm lens. So I continued to take pictures and I was serious enough about taking pictures and doing photography, even though I still didn't consider myself a photographer, that I bought my first Nikon in 1984, had a Nikon, it didn't even, it had a good lens and I had photo equipment and tripods and I still didn't consider myself a photographer. I'm a painter, I'm an artist, it's really true. So what happened was in 1988, a very good friend of mine, a guy and you'd see what I've got laid out on my table and you can see in my studio there are pictures of clowns that people are painting seriously. I enjoy all kinds of things that, and I take the work seriously, I don't necessarily always poke fun at Kitch, I take this as an expression of in many ways contemporary American folk art even though it doesn't fit the bill necessarily in academic terms sometimes. So I've always been interested in Kitch, I've collected baseball cards, comic books, I'm interested in figurines and dolls, you name it, but I was making very serious large abstract paintings and a friend of mine said, a guy I grew up with said, you know, for a guy who likes to fool around as much as you do and somebody who has a lot of opinions about everything and everybody, how come your artwork is so serious? That was his question and the truth is, I didn't have an answer when he asked me and for weeks and weeks I didn't have an answer and it really started to bother me. And so I had, I guess what you call a little, I got lucky, let's put it that way, I got lucky, I came to a conclusion over time that some artists never do and I did it at a fairly young age, I started doing some experimenting and I went to some of the professors that I trusted in graduate school and they all basically said the same thing, you better indulge your eccentricities, you're single, you're young, you don't have anybody to support, you don't own a car, you don't have to pay life insurance, you know, you're a young guy essentially, have some fun and I did and I went back to some of my old abstract paintings that were pretty good and I cut them up and literally wove them into black velvet paintings and that was Presley and all kinds of other things, the Pope, all kinds of popular culture iconography and at that time also in graduate school I started taking graduate level photography classes with a guy named Mark Feldstein and I laid this out to him and told him how troubled I was by my denial of photography and my not understanding anymore, you know painting didn't make sense much sense to me and he said the same thing, well if you're going to indulge your eccentricities what are they and we spoke about it and he's the one who really convinced me that I really want to start taking pictures of other people doing what they do, whether it's art or some other act, but he was the one who helped me identify the fact that what really is my strongest, most passionate interest is public expression in public on the side of the road, so that summer between my first year and second year of graduate school had a girlfriend at the time, the trip broke us up that we took but we took it, we went all away from Central New Jersey, I was living in New York but she had an apartment in Central Jersey, we went from Central New Jersey, through Boston, through Cape Cod, all the way up to Maine, through Maine, to New Brunswick, Canada, to Nova Scotia, to Cape Breton Island, to Labrador, no Newfoundland and then we ended up in Labrador, okay, but all along the way and you'd have to have a pretty good sense of yourself and of what it is that you need to do to make art and I did, so all along the way I limited myself to taking pictures of only things that were for sale in gas stations and/or right on the side of the road by a gas station and it turns out in Maine that's a lot of things to photograph, you know, who knew, so that was the genesis of this whole thing and I looked at those pictures when I came back and in the end I had taken pictures of all kinds of folk art, all kinds of kitsch objects and, you know, of course there are cemeteries next to gas stations so I had limited myself in a certain way which was very, very productive in terms of my art making, you know, as a photographer and I did the same thing, I sat back and thought a lot about it and little by little I continued to make these collages because I like cutting things up and putting them back together again and I have a good visual sense of what I like but little by little I moved further and further away from painting and what many people would describe as studio art, you know, and I really started taking pictures of things by the side of the road but the one thing that I should mention is important is this guy Mark Feldstein had many, all of us in the class do, he wouldn't let you use a camera unless you made it so people were making pinhole cameras and people were making all kinds of cameras, this is a graduate level photography class, you had to, you had to make your camera, so I didn't really like working with pinhole cameras and he allowed us to order 100 toy plastic cameras, they're worse than the old brownies, there's no focus, there's no flash, there's no aperture, nothing, in fact the cameras are so bad that we used to have to tape them with electrical tape so the light wouldn't bleed through on to the really good roll film, of course then when I got back from Maine and I looked at my film that I shot, I realized that I liked the fact that light was bleeding through, yeah it was a nice effect, that and the fact that there was no focus and if you shot right into the sunlight with one of these cameras, now they make them their whole good cameras, you can pay up by $25 you can buy one, we were buying them for $1, so that was my start into morphing into a photographer, or I take that back, morphing into a person who would call himself a photographer but I had always been a photographer and I have pictures and there's no sense in going through the litany of things that I photographed from the time I was 10 years old but I have some pretty good pictures and I've always had a good sense of composition, always had a good sense of timing, my timing has always been good, so I would say that my experience as a photographer has been, it's been a lifelong experience and that I'm a fundamentally different person as a photographer than I am as a painter or as a fine artist, I would argue that there are two very different pursuits and it's very hard to do both simultaneously, you think you'll be chosen the right one? Well for now I'll tell you what I'd like to do, I'd like to have 10 more years, I'd like to have a crack at 10 more years back in my studio, you know, I've been doing this full time for 12 years now, I mean we're almost at the 12 year anniversary of the attacks and I was always taking pictures, you know what I'm saying, but this is one project, this is one project I've been working on other things as you know but this is the thing that has been the predominant project and force in my life, I mean this is, this is my identity as a photographer and my identity as an artist, fortunately for me and I made myself a promise, but I made myself a promise that I wasn't going to let the work that I was doing surrounding 9/11 define me, because I saw that happen early on to a lot of people, so the hardest thing that I've had to do, even though you didn't ask me, is to not let this work define me as a person, while at the same time trying to define culturally and artistically the pursuits of other people who have tried to define themselves and their Americanism and their patriotism and their hatred of war and their love of peace or whatever it is, I'm in the position of having to make sure that I'm far enough away from this, that it doesn't take my life over and define me, but I have to be enough engaged in it that I can express a point of view without being political, that's the trick. What was your 9/11? I had already moved up state full time, my wife and I moved up here in late '97 when my, our daughter was seven months old, but I was supposed to be in the city that day and for whatever the reason I can't remember, I didn't go down, because at that time I was still commuting back and forth to New York quite a bit, I should tell you that I had aloft in Chinatown on Canal Street and I, that I had three windows and you could look at that with those windows and see the towers, I lived with the towers every day all day because when I went out of my loft to go to the subway, when I went out to get a plate of beef with broccoli over rice, when I went out to take a picture, when I went out to do anything, the first thing I saw was those towers and not only that, I had friends working in the towers, I had a girlfriend who worked on 102 in the south tower, so they were, notwithstanding the fact that I didn't work there, they were really like many New Yorkers, they were a part of my life that I just came to understand that they were the World Trade Center towers and I've subsequently found three or four, actually five pictures of myself, one on the Brooklyn Bridge, one on 6th Avenue in Manhattan, I found pictures that had been taken to me by friends over the years with the towers looming behind me, you know, and it's nothing special to me, those towers were there for everybody. And so I sat in front of my TV, you know, in disbelief like everybody else because I got a call from a good friend's wife who said you better turn on the television, just like everyone else heard something similar, a plane just crashed into the, you know, the towers. And so it was unusual, I started making some phone calls to my friends who I knew worked down there, and I knew a friend who was working had a day job down there doing some photographing, and then, then the second plane hit and then, you know, that the rest is history, so to speak, and unfortunately tragedy as well. But the thing, my 9/11, as it relates to this book and as it relates to your question about me, is that that morning I had already driven my daughter 20 miles to her school and had arrived home already. And later that day, I had to pick her up, I believe around three o'clock. So on the trip down, the 20 mile trip down and the 20 mile trip back, I saw so many flags that had come out, so many phrases on the side of the road, so many, I mean, I, this response was direct and immediate, everything from we need world peace to FU Osama, day one. And so I started taking pictures, as I said earlier, when we started speaking, I thought it would be good source material for my, my collage work and the things that I'm doing. And I realized very early on, I took 40 rolls of film because I would, I shot film through 2003. And I've got boxes on my shelves over there, there's over 10,000 negatives there. But I have the good fortune of having three very, very good friends who are fabulous photographers, and they all convinced me that I had to go digital. For something like this, especially. Well, I, they all said, some version of you need to stop the bleeding, you can't keep doing this. So, so, you know, so I went digital, but I looked at the first 40 or so rolls of film within three weeks, I went down to the Rite Aid and had them develop because I wanted it, I knew at the very least, based on my interest in the side of the road, and my interest in the expression of other people, because that's really why I gave up painting, as I mentioned to you before, and not in this interview, I have a master's degree in fine art and painting. But I moved away from that because you have to be very self-involved in a certain way to be in your studio and generate ideas and work. And I realized, as I said, that I was more interested in what was going on in other people's heads than my own. So I looked at these 40 rolls of film, each roll 36 pictures to a roll. And I said, oh my goodness, there's, there's something palpable here. This looks like a conversation to me. You know, F.U. Osama, we need world peace. I lost my brother, you know, whatever it was. And I'd never seen anything like that. And as I said with regard to the Europeans, we don't have any experience in that. We don't, this is new ground for us, so to speak. So I decided that I would start doing it every day and I would get in my car and drive to New York, except it would take me nine hours instead of two. And on the way home, maybe even longer, and I would try to get lost. And I was, I did some driving in college for a candy company and a pharmacy. And I knew the territory between South Central New Jersey from the Trenton area all the way up to Albany really well. And I lived in New York for 16 years before moving. So I knew New York City pretty well, because I'd also coached basketball. And I'd done some recruiting in a lot of different neighborhoods and all five boroughs. So I had a pretty good idea where to look for murals, where to look for people with tattoos. And so I used all of those things that I had been, that I had been becoming and put them to good work, including this ability to negotiate for a picture, to negotiate for my safety sometimes. And in fact, in the book, I talk about this friend of mine who became my assistant. And very often, he would speak Spanish and offer somebody $20, for instance, to move a truck so I could photograph a mural, you know, and because I wasn't getting things done all the time on my own. And so I'd always have an eight foot ladder. So even if he didn't move the truck, I might have a shot at getting above it, you know. But so that's, that's my experience. That's my 911. That's what I did from day one. Jonathan Hyman, author of The Landscapes of 9/11, a photographer's journey. Thanks so much for your time. And that was Jonathan Hyman on The Virtual Memories Show. You can find his book, The Landscapes of 9/11, a photographer's journey on Amazon and in bookstores or direct from the University of Texas Press website. His photos are awfully moving. And I've dug the essays that I've read so far. I recommend the book if you're interested in trying to get an understanding of what average Americans, I guess you could say, how they responded in terms of art to the September 11th attacks. The second part of our 9/11 special will go up next Tuesday, September 10th. And that'll feature a conversation with Thane Rosenbaum, the law professor and author of Payback, The Case for Revenge. And that's a fun one. After that, we'll get back to a bi-weekly schedule beginning on September 24th with a conversation with Philip Lopate, the great personal essayist. Meanwhile, you can subscribe to The Virtual Memories Show on iTunes by searching for virtual memories and clicking through to the show's page. And if you go to iTunes, do me a solid and post a rating and review of the show while you're there, because there's only two so far and I'd love to find out what more of you think about it. And the full archives of The Virtual Memories Show are also available at our website, chimeraobscura.com/vm. If you visit the site, you can make a donation to the show via PayPal. There's a little link right there with a donation button. And that'll help offset my web hosting and travel costs and new microphones and other stuff that I need, maybe like a engineer who can keep me from having so many plosives in the next podcast. If you make a donation, I'll make sure to give you a shout out in the next show. And I'll also send you a copy of a short story I wrote a few months ago. And we're also on Twitter at VMSPod on Facebook at Facebook.com/virtualmemoriesshow. And Tumblr at virtualmemoriespodcast.tumblr.com. Until next time, I am Gil Roth and you are awesome. Keep it that way. For America, they've only come to look for America, for America to look for America. [Music] [Applause]