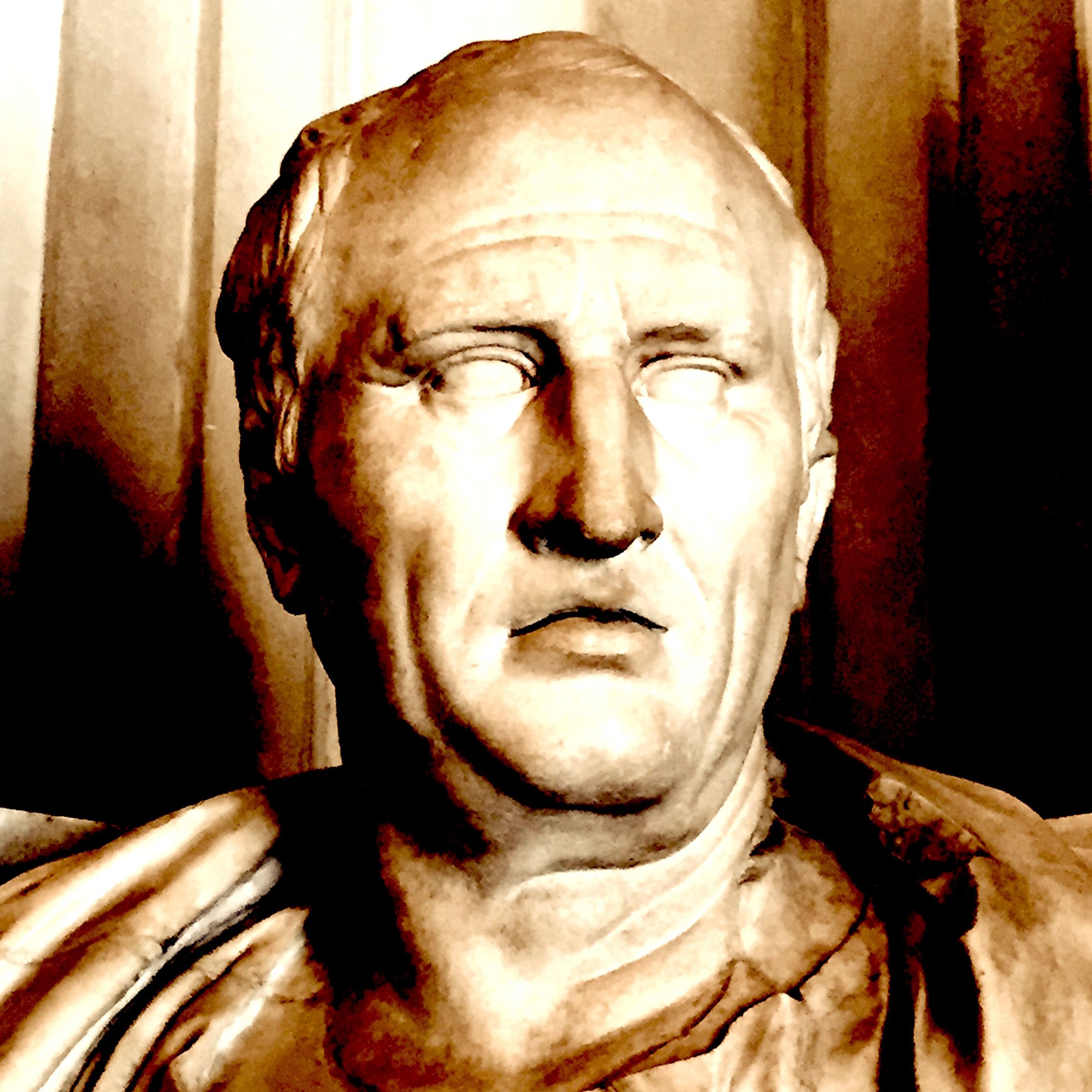

(upbeat music) Welcome to the Sadler Lectures Podcast. Responding to popular demand, I'm converting my philosophy videos into sound files you can listen to anywhere you can take an MP3. If you like what you hear and want to support my work, go to patreon.com/sadler. I hope you enjoy this lecture. In Book 3 of Amiens, Cicero has Cato provide us with a systematic account of Stoic ethics. And central to Stoic ethics are the cardinal virtues, wisdom, justice, temperance, and courage. Wisdom is the most important of the virtues. And it's accordingly very important that we understand what wisdom is and how it works. So there's a bit of a digression in there about wisdom and the other arts. The word that Cicero uses is our taste, which can mean arts, disciplines, sciences. This turns out to be quite important because it does help us to better understand the extent, scope, and workings of this virtue. Interestingly enough, what Cicero is gonna have Cato do is say that wisdom is in fact like some of the other arts. And the analogy that he draws is actually to some arts that were not highly regarded in his own time. So this tells you that he was really quite serious about this. Acting, acting on a stage and dancing. So how is wisdom like that? Well, he starts out by talking in very general terms. He says, "Our limbs are so fashioned "that it's clear that they were bestowed upon us "with a view to a certain mode of life." (speaks in foreign language) A certain measure, a certain mode, a certain way, a rational way of living. So our limbs are given to us in that way. And he goes a little bit further moving to the interior of us, what you can say. So our faculty of Apetition, the Apetitsioonomy that the Greeks call Hormé, at least the Stoics do, that was also given to us for a given mode of life. Not to desire everything, not to be moved towards everything, but certain things. And he goes on further and says that the same thing can be said for reason and perfected reason. Notice the difference there. Not just reason itself, but reason that has been brought to its fulfillment, Ratsuo at Perfecta Ratsuo. And then he says, "Just as an actor or dancer "has assigned to that person, not any, "but a certain particular part or dance. "So life has to be conducted in a certain fixed way, "not in any way that we like." So, we could say the same thing about a singer. One thing that ruins choral ensembles are people who want to be the soloist, even though it's not time for them to solo. And when they do solo, they don't sing it straight, but they engage in all the sort of American idolesque trills and extra notes in here and stuff like that. That actually screws things up. Or if you're an actor, you shouldn't be ad-libbing. You should follow the play unless you're so advanced that you actually can make it better. So many things are ruined by people thinking that they're gonna make things better. We can even say things outside of the scope of this. As examples like cooks who are not particularly gifted, but have watched so many cooking shows that they think that, well, I'll just add truffle oil and that's gonna make everything even better. Or it's gonna make it power, or whatever these celebrity chefs say about their particular confections and creations. Well, in a lot of cases, you're actually better off sticking with the recipe, sticking with your part, sticking with what your assigned dance role is in the choreography, not dancing this dance when you're supposed to be dancing that dance. And so, just as an actor, a dancer's been assigned particular parts or dances. Our life should be conducted similarly, he says, in a fixed way. And I really like this comparison because if you know anything about music, acting, or dance, you know that even when you are assigned a particular part, you're not doing it like a robot, unless you're supposed to be a robot, of course, you're interpreting it. And that's the way that wisdom is. We have fixed roles or fixed responses that we should have, but that doesn't mean that we're doing it in a purely mechanical way. As a matter of fact, that would be not wise. And he uses the words conformable and suitable in the Latin conveneans and consanteum qué. Dicky Mosi says. So, this is an important phrase because this also ties in with being in accordance with nature, which is central for the Stoics as well. There are some important distinctions that we're gonna get to in a moment, but I wanna draw out one other really important similarity. He says that dancing, wisdom, and acting are unlike the other arts like seamanship or medicine. How so? Because in those other things like, you know, sailing or seamanship, right? There is a goal and that goal is outside of the activity itself. It's to get stuff from point A to point B without foundering the ship and dying. In medicine, it's to produce health, to, you know, eliminate disease, to do whatever it is that we're doing. The goal of medicine lies outside of medicine. In acting or dancing, the end is actually in the actual exercise or in Latin, the effect CO. In other terms, it's what we would often call a praxis where the goal lies within the activity itself. If somebody says, why are you doing that? Well, to do it because this is a good thing to do. Wisdom is like that. It's not that wisdom is just good because it brings about beneficial results that we want. No, wisdom consists in living well. So it's a central part of the good life. There are some important differences, of course, between wisdom and these other arts. So as he says, right actions, if we understand them in the general sense or we understand them as rightly performed actions, or the mata in the Greek that Cicero has Cato referred to, they contain all the factors of virtue, whereas acting, dancing, that doesn't contain the totality of the art in any particular movement, right? The movements are, to some extent, discrete. Another important difference is that, as he's going to say, wisdom is entirely, the translation here is self-contained, but I think self-focused might be another better way of talking about it as well. Sola en im sappientia, only wisdom itself, en se tote con verse est. Con verse means to be sort of like turned inward on itself or turned with itself, verse, right? From verterre. And so wisdom is going to be self-reflexive. Wisdom, unlike these other arts, is going to be focused upon itself. The wise person will continue to ask him or herself, is this in accordance with wisdom? Am I genuinely wise, or can I become wiser, right? Whereas that's not going to happen with dance. Of course, a dancer, actor can say, "Can I become a better performer according to the standards of my art?" But it's not the art itself or the faculty within us itself that is bringing that about, that engagement, that reflexive discussion. He also says, quite interestingly, that wisdom includes or encompasses, and he brings up several different virtues, magnum ni ni mi, magnatutidim aani mi, right? Justice, yustitiam. And then he says, and sort of, sense of superiority to all the accidents of man's estate. What omni a quite hominy, oxidant, infresse esa yudiketh, right? So wisdom is actually encompassing. Again, complexity to it. Coming from this plecure, this folding, it unfolds within itself, or it unfolds into all the other virtues, all the modalities of justice, all the modalities of courage, which includes great soldness or magnanimity, all the various aspects of temperance, and anything else that we would think would be good. Wisdom includes all of that. That's not something that we can say about acting or dancing, particularly the talent for acting or dancing that a given person has contained within themselves. So he goes on and he says, this isn't the case with the other arts. Again, even the very virtues I have just mentioned cannot be attained by anyone, unless he's realized that all things are indifferent and indistinguishable except moral worth and baseness, which is something that wisdom teaches us and helps consolidate within our minds and within our lives. So wisdom can be understood as a sort of art of living, living well, living in accordance with reason, but it's not purely about reason, it also has to do with our appetite or desire, and it even has to do with what we do with our bodies. So wisdom itself is an art more similar to dancing or acting than it is to, you know, seamanship or finance or pick whatever other extrinsic and oriented art you're going to talk about. This is, like I said, seemingly kind of a digression about the nature of wisdom, but I think it helps us to much better understand just what wisdom is from the stoic point of view. - Special thanks to all of my Patreon supporters for making this podcast possible. You can find me on Twitter @philosfor70 on YouTube at the Gregory B. Sadler channel and on Facebook on the Gregory B. Sadler page. Once again, to support my work, go to patreon.com/sadler. Above all, keep studying these great philosophical works. (gentle music) (gentle music) (gentle music) (gentle music)