Welcome to Big Blend Radio's Nature Connection Show with Lisa and Nancy Publishers of Big Blend Magazines and Nature photographer Marco Carrera. Welcome everybody. We are excited because the Nature Connection Show is expanded from being every fourth Friday to every second Friday and fourth Friday because we've got a lot to talk about, not only climate change and in the environment but also talk about endangered species and then also ways to coexist with nature and connect with nature, obviously, so that we can all live happily ever and in harmony. How about that, Marco? Does that sound right? You know it sounds the best that your word coexist. Ah, I like that. Yes, I like that. I love the word coexist because that means we can all be doing our thing, not harming each other but then not, you know, overwrite each other which is really good and perfectly talking about that. Today we have acclaimed climate and environmental scientists Rob Jackson joining us. Rob is the chair of the Global Carbon Project, a senior fellow at Stanford's Woods Institute for the Environment and Precourt Institute for Energy and a professor of earth science at Stanford University is also an author and he's joining us to talk about his new book It's called Into the Clear Blue Sky, the path to restoring our atmosphere and it is out now through Scribner and you can also go right to his website. It is robjaxsonbooks.com. It is an honor to have you on this show, Rob, how are you? I am fine and thank you so much, Lisa and Margot. It's an honor to be here. Hey, we're excited about this because I think, you know, your book number one has some optimism and a lot of times when we talk about climate change and, you know, everything that goes with it, there's like so much fear and I think we do need a good dose of fear to make, you know, some change that we realize like time is ticking. But you also offer solutions and I think this really comes from, you know, you've done so much work right in your career as a scientist in working to reduce tons of greenhouse gas emissions, which we know really helps everything from our air and to create blue skies, right? And also have clean water. It seems that those are a direct relation, which means we're all healthier and happier. So can you give us a little bit of background on how you got into the world of climate science? I can. I was trained as a chemical engineer and I went to work for the Dow Chemical Company after college and after four or five years at Dow in the petrochemical industry, I went back to school, to graduate school, to study ecology and environmental sciences. And over the last few decades, I've been studying the environment, everything from grasslands to forests, and increasingly in the last decade or two, human built infrastructure, cities, our streets, our homes, our air quality, our water quality. So kind of combining an ecological and an engineering type perspective to ask how can we, how can we clean up the earth and how can we leave the earth a better place for our children, something that everyone wants? I love it. And in your work, the fact that you have actually reduced millions of tons of greenhouse gas emissions through your work, there is actual proof and evidence that we can make positive change, right? We definitely can make positive change. We can make positive change individually, and then there are some things that we can't do on our own that there has to be systemic change to fix. Individually, we can choose to, you know, we can choose what fuel we use, clean electricity over gas in our homes. And in each of these choices, we're not only helping the climate, we're helping our health today, our stoves, our gasoline powered cars, they don't just release greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide and methane, they release ozone, mocks gases, pollutants that, benzene, pollutants that still kill Americans, 100,000 Americans every year die from coal and car pollution still today, even though our air quality is better than it was when I was a boy. Wow. Wow. I mean, Los Angeles is a great example. I mean, when I left Los Angeles when I was a little kid, about a year and a half, and I had all kinds of breathing problems, and this was in the mid 70s. So I'm really young now, but anyway, I had all these breathing issues and it's developing asthma and always had a running nose, always was coughing. And then my mom and I moved to Kenya and I was out in the bush, you know, for the first few years that we were there and I swear in the next, within two to three weeks, all my breathing issues, all my allergies, everything, even food allergies went out the window. So I wonder how far smog can really affect us, you know, in just that example. Yeah. That's an amazing story. And I can't say that I'm surprised. We surround ourselves with pollutants that are unnecessary, you know, one in five deaths worldwide is attributable to fossil fuel pollution, that's 10 million cents a year when we have clean fuels already available. And I already mentioned ozone and not Knox gas is benzene. This is the number one reason for me to emphasize climate solutions today. It isn't just about our grandchildren, it's to make ourselves healthier, to make our children healthier right now, not in some distant time or for some distant generation, fossil fuels kill people and clean solutions are available. Can we go through what are good gases and bad gases? There's classical gas and that's a good song, but you know, there's, you know, and we're a me thing, we've heard so much on that. And, you know, everyone's like, you've got to become vegan because of the methane thing. And I feel like if we go to extremes that people are not going to make changes because it's like, sorry, you know, I feel like if we can get in the middle road, maybe that will help. I mean, what do you, what do you think let's, let's start with methane. What exactly is methane? Is it all cows? Is it all that that? Is it the cows fault? It can't be the cows fault, but what we did, right? So what's the biggest threat when it comes to methane? The sources of methane are energy related to every fossil fuel that we use leaks a bit of methane when we extract it from the ground from oil and gas oil or from a coal mine. Methane leaks in our pipelines under our city streets to get it to our homes and methane leaks inside of our homes in the pipelines in our walls from our stoves from our furnaces and water heaters. Methane is the second most important greenhouse gas that we control. Carbon dioxide is the first carbon dioxide public enemy number one for climate. It's long lived. It lasts for thousands of years in the atmosphere. Methane has contributed about two thirds as much warming as carbon dioxide in recent decades. I think that is public enemy number two. But it's the focus of my current climate research because it's the only gas, powerful greenhouse gas that leaves the atmosphere relatively quickly and by that I mean within a decade or so. What that means is that if we could eliminate all methane sources today with a magic wand, the atmosphere would cleanse itself and go back to pre-industrial health within a decade. That's what I think of as restoring the atmosphere and that's my dream as a climate scientist. Wow, wow, that would be amazing, right? So what would we need to do to do that? I mean to get rid of, I mean you were talking about there's clean natural gases, right? So my mind is I get twirled around on this too. Would that be fracking because that's like a, at some point they were saying that was natural and clean and I just think, you know, I see fracking across the country as we travel and it's outside parks, you know, I've seen oil being, you know, drilled out in actual parks in national wildlife refuges, seriously, pelicans floating next to an oil derrick. Like what is this, you know, this cannot be good. So when it comes to natural and clean, is fracking a good thing or a bad thing? In my mind it's not so much about fracking itself, fracking is a way of getting oil and gas out of the ground. It's a very effective way. There are issues when it's done badly with water and air pollution. The real issue though, the core issue in my mind isn't fracking itself, it's our reliance on oil and gas, the requirement, the need for this oil and gas that makes us drill deeper and farther and ever more aggressively, so it isn't, I think it isn't fracking that's the bad actor, it's the benefits of getting off the addiction to fossil fuels, the oil and gas that we need fracking to get out of the ground now. Okay, okay, cool. So all right, we're getting there then, we're getting there and understanding all of, okay, all these things, but so electric cars, that's okay, but then people say that batteries are also part of drilling, right? So what about that, does that, are those okay or not, trying to figure out? Yeah, it's hard, there is no technology to provide billions of people on earth with energy that is environmentally free, EVs in my opinion are much better than gasoline powered cars, but they're not perfectly clean, you still have to find lithium and minerals, you have to make steel and you have to build roads, so just as for all climate solutions we need to think about using less as a starting point, reducing demand for things that harm the earth and then decarbonizing or cleaning up our manufacturing for those objects. So cars like EVs are, I think they'll win eventually, not just because they're better for climate, because they're simply better, and they're faster, they may have essentially no air pollution, at least locally, they have less maintenance costs, I have a chapter in my book on electric motorcycles and I mentioned that I went to test drive one, and it was the fastest I'd ever driven, it was thrilling to drive, and it's a better solution for the climate. So the reason to support things like EVs is the climate, but it's also that if you live in Los Angeles or in a city, if we filled our cities with EVs instead of gasoline powered cars, the air in the cities would be better today, again, not in some distant generation. Better yet, sorry, better yet, pardon me for going on, would be to walk or bike or take public transport, but if you have to drive, by all means drive a faster, cheaper and easier to maintain EV than a 19th century, early 20th century gasoline powered car. Perfect. Margot? Yeah, along that line is how to power the car. Electric versus hydrogen vehicles, do you see any difference or anything better in one or the other? I do, I support hydrogen vehicles, I'm sorry, I support EVs over hydrogen vehicles, and let me explain the difference. I think hydrogen, we think of hydrogen as the champagne of fuels, it's an amazing fuel. The problem with it is that in general we have to make it instead of extract it, and the way we make most of our hydrogen these days is to start with natural gas and to use a process called steam reforming. So it's a dirty process to make it, and increasingly in the future we'll make it with clean power, green power like linking hydropower to electrolysis, and I cover that in a chapter in my book for the world's first green steel production in Sweden. So I support hydrogen for large industrial sources, if you're a steel maker and you have a blast furnace that requires an oven at 3000 degrees, hydrogen is a great way to replace the coal in that system. But for a millions of vehicles in the US around the world, each of those vehicles will leak hydrogen. Hydrogen is the world's smallest molecule, so anything that leaks methane, any pipeline or system is going to leak even more hydrogen. So we don't want, in my opinion, we don't want millions of vehicles zipping around the earth all leaking a bit of hydrogen. I think it's a great fuel for large industrial sources but not for distributed sources in our pipelines or in our vehicles. Okay, thank you. Yeah, it's sounding like we need to have, and this kind of goes back to our interview with the Texas Aquarium, Marga, where he was talking about that we need a mixed portfolio, basically, for what we're doing in change. Because some things will be, you know, if your trucks, you know, shipping goods, you know, goes across the country, they're going to need real gas, right? And then when it comes to in cities, especially metropolitan areas, they're going to use more EVs. And I love the idea of walking in bicycles, it's just healthier, right? And then public transportation. But even public transportation is starting, you know, we've got things like Amtrak, you know, I don't know how clean they are, how clean, like something like Amtrak would be for the environment. But I figure it's, if you've got more people getting in an Amtrak, it's probably better than individual cars, right, those kinds of things for long-distance travel. Yes, and we can clean up our rail lines and public transit systems more quickly, and in some ways more easily than we can each of us individually doing the same thing. So yes, I think anything we can do to make our public transport better, we don't do a good job of public transport in the U.S. and you mentioned you grew up in Kenya, you go to other countries. You go to South America, for instance, and the buses are fantastic, they're comfortable, they're family-friendly. Everyone uses them instead of in the United States, where, you know, not the full spectrum of society typically gets on a bus in a typical day. That's not true in other countries, that's a choice that we make in the U.S. Yeah, and England does it. I mean, they go by a rail all the time or, you know, the tube, you know, things like that. So it's, you know, Europe is doing it in Europe. I mean, we look at Europe, everyone's walking, you know, and the other thing with long-distance, you know, and I look at, you know, you're talking about really walking around if you're in a city doing that kind of thing, but it's also about where we get our food. And we're starting to see some good changes happening with rooftop gardens, like chefs having their own herb garden or just outside the city or even urban farming and stuff like that. Food and crops come local, farmers market, CSAs, things like that. Does that help us in regards to fossil fuels in a big picture at all? I think local food production is a good idea. I'm going to go to our farmers market weekly and participate in a number of activities at my own garden and fruit trees. I think we do tend to overemphasize the idea of food miles. We think of an apple coming from New Zealand to the United States, and that sounds terrible. But in the grand scheme of things, that transportation across the oceans on a container ship is a pretty small part of the emissions. So locals, locals better, but yeah, sometimes we get a little bit too hung up on the idea of food miles that I think is not always productive. We haven't, if I may, we haven't talked about agriculture, I've emphasized fossil fuels. And for a gas like methane, agricultural sources outweigh the energy-based sources. So the cows, for instance, in their kin, belt more methane than the entire oil and gas industry worldwide. We don't think about our food within our choices, our dietary choices as influencing climate and of course our health. And once again, there are benefits in climate solutions for helping the planet and for improving our own health by eating less beef and red meat, eating more plant-based diets, and eating in a way that's healthier for us individually. I think that that was something I was saying at the beginning too, because it's also what we're doing to the topsoil and the land and the waterways by overdoing, right? And we've done some interviews over the years with the Reducitarian Organization, which I think is pretty cool because I don't, I think if we go up to people eat meat every day or something and say, okay, you've got to stop meat all the way across the board, that's like, that's not going to pretty much, the success rate isn't going to be high. But if you start to reduce every day, I mean, we do, you know, shows with Dr. Jackie who's a cardiologist and she's like, plant, fill your plate mostly with, you know, fruits, vegetables and whole grains, you know, you don't need to have the meat being the biggest portion, you know, and we don't need it every single day. So just even for, I feel like whatever we do that's healthy for us is going to be healthy for the earth, right? Don't you think it kind of goes hand in hand with that. So but the, you know, when you look at what happens to our air and our waterways, I mean, you can smell it. I mean, traveling the country, I don't care how good your air conditioner is, there's places, I mean, it stinks and I go, wow, and there's houses and people living right next to these, you know, plants, you know, all the, you know, the fossil fuels and all of that kind of stuff. And then agriculture, it does stink, methane stinks, I'm just saying. So it's, I kind of feel like if it stinks, it can't be that good, Rob, right for us to be living in. Yeah, so literally methane doesn't stink, it doesn't have an odor, it stinks in our pipelines in our homes because we add sulfur gases to it so that companies add sulfur gases to it so that we can smell it. But when you smell methane driving down a car by a cattle feedlot, you're not smelling methane, you're smelling the urine from the cows and the, you know, the manure that builds up. So that just because methane doesn't stink doesn't mean that it doesn't cause problems, so I have a chapter in my book called Planet of the Cows and I think it highlights my philosophy on climate solutions. It starts with an interview of Pat Brown who was the founder of Impossible Foods, a plant-based food company, Impossible Burgers and such, and Pat all about sort of reducing beef consumption and he wants to put the industrial beef industry out of business, that's sort of his mantra. But taking a Pat Brown approach, we can eat less beef and as you said, Lisa, it doesn't have to be everyone being a vegan or everyone being a vegetarian. Every meal that we can regularly reduce our beef consumption helps the climate and makes us healthier. But to contrast reducing demand, we also need to find solutions and new technologies that help us cut emissions for however many, in this case, cows that are left and I interview a scientist named Ermias Cabrabe who studies feed additives for cattle. He grew up in Africa, in Eritrea, he has a very different view of meat than Pat Brown does for him. Meat is part of their culture and animals were part culture. He told the story that the first suit he ever owned for a graduation, his uncle went out and sold a goat or a cow to pay for his suit. So he doesn't see a world without cows or trying to end beef consumption. He wants to reduce the emissions from cows and is working on feed additives to do that. So there's not an easy solution, but there are feed additives that can cut emissions from cows, 80% or 90% as Ermias has shown. And the trick is how to get those feed additives to a billion plus cows across the planet. So for cattle, just like for fossil fuels, use less, reduce demand. That's the first step. And the second step is decarbonize or reduce emissions for whatever animals or infrastructure is left. What about also, you know, as we're tearing up the land for the cattle, right? Because I mean, even in our national forests, they lease out land to cattle grazing and very cheaply. It's like, I think I can't remember what the latest number is, but it's like two dollars or three dollars, a cow a year. And the grazing is they're not native to these landscapes, you know, in fact, I think most cattle actually come from a different region if you really look at, you know, their global pattern, their footprint, you know, Asia and Africa definitely in some parts of Europe. And so when you look at what they're doing to the actual wilderness landscapes and taking in regards to water, at least they're a free range, but it's actually not good to the environment because they're not native species. There's wars over wild horses in cattle, which we've covered a lot on shows in the past. But it's kind of, it's a sad thing to see what happens with that because I also believe doesn't that hurt our waterways. And then when we look at that kind of thing, agriculture, like mass agriculture, then we look at actual, you know, drilling for oil and all of that combined, all of this space takes a toll on the actual habitat. You know, mining takes a toll on the habitat and the restoration, I think it, I mean, I've been to places where they have restored actual quarry sites. So I've seen it happen. I've seen that, you know, it just takes a long time. And I think we need to focus on that. I think you cover that in your book too, don't you? It was actual, you know, putting back the ecosystems that we've destroyed. I do. Yeah. First, for cattle, we did have native grazers here, the bison that were abundant. Yeah. And have cows here, it's true, there were prevalence common grazers that in some grassland systems in particular do require some grazing. But the number of cows that we have far out, you know, out numbers of what would have been here naturally. As I mentioned, I think earlier, there are about a billion and a half cows on earth because of our need for beef and dairy. So there are more cows than almost any other large mammal, and that's a human decision. And it isn't just about the methane burps, it's the deforestation that goes with clearing land for new soybean growth, soybeans fed to cows and beef production. 80% of current deforestation in the Amazon is driven by the need for beef production. We use a lot of water for our cows. I was researching this book, I learned a statistic that shocked me and I studied environmental statistics for a living. That statistic was that half of all Colorado River water that goes to irrigation irrigates plants fed to cows. So half of all the water that we take out of the Colorado River for irrigation goes to irrigate things like alfalfa that we feed cattle. And we certainly have better things to do with our water than that, more valuable and better for the environment. It is really true about the Colorado River, and it's a devastating thing that's happening right now with that and I don't think the damming helped it either. And when you see what happened with Lake Mead, recently we were up in that area earlier this year and Lake Mead is not what Lake Mead used to be at all. And when you see that, there are certain areas that cleaned up the area. UMA Arizona did a fantastic job of 49 agencies including Native American tribes getting together to restore the lower part of the Colorado River. But the Colorado River is not like we were talking about earlier, not even getting on a separate show, not even making it to the ocean anymore, which is the function of a river, right? It goes to the ocean. It doesn't make it there. So we have so little water in the Colorado River. But the lower Colorado River area was in UMA Arizona, just such a great restoration example and I use it all the time because, again, agencies and different cultures came together to make this one-tracked clean. And UMA is a massive agriculture zone, massive. And it is like the winter, you know, vegetable producer crops and they have citrus, they have lettuce, all of it. And so you've got to look at what was going in the waterway, right? And so they started a lot of invasive species, plant species came from agriculture. And so they cleaned up the invasive species, started to put their natives back, including the cottonwoods. And you can kayak or canoe down the river and you can tell immediately when you hit the restored zone, all the beaver came back, all these birds that weren't there anymore. They have over 400 birds that make UMA home in this area, in the wetlands. The pelicans came back and there's like a certain flycatcher and warbler that is now coming back that went away, the cuckoos are coming back. And so everything is starting to live that co-existent life. They took what was a landfill and turned it into a solar farm. And it's also part of a park so people can see that, have one of the best playgrounds that are interactive for kids and also accessible. They put in hummingbird gardens with native plants and, you know, it's absolutely amazing. So families can go and recreate there. And at the same time, nature is existing and I think that is super cool. So it's like, this is this little example. So things like that, we can do that, Rob, isn't that what we should be doing? Does that help the actual atmosphere? Does it help combat the agriculture a little bit, those little pockets? It does help, definitely. In fact, let's spend a little bit of time on this idea of restoration and restoring the atmosphere and restoring the earth entirely, which we touched on a bit before. But I think not enough. I think my book is a repair manual for the planet. It highlights the people and ideas needed to solve the climate crisis. Maybe a how-to guide for restoring our air and our health as we move from climate despair to climate repair. That's really my goal. And I became excited about this idea of restoring the atmosphere when I look around for a couple of reasons. For one reason is that I don't think arbitrary temperature thresholds, like 1.5 and 2°C increases are motivating people to change behavior. People don't understand why those numbers are important. They are important, but they're abstract. I think the idea of restoring the atmosphere is a better motivator and the Endangered Species Act, for instance, it doesn't stop at saving plants and animals from extinction. It mandates their recovery. So when we see gray whales breaching on the way to Alaska each spring, when we see grizzly bears in the Yellowstone meadow, bald eagles or peregrine falcons soaring overhead, we celebrate restoration, a life in a planet restored, and our goal for the atmosphere should be the same to put it back to the way it was and to restore it to pre-industrial health. Yeah, I love that because even your book is really restoring the atmosphere, right? And when you think about what the word "atmosphere" is, when you think about going into a restaurant, you think about what's the atmosphere? Is this a family-friendly kind of place? Is it a hoity-toity date night? Is it, you know, do you need to put your best shoes on to go in or is it relaxed? Is it clean? Is it a clean atmosphere? And you know, we think about like as a vibe, as a feeling, and atmosphere has a feeling. And I think that's something that we emotionally can connect to is that word "atmosphere" and restoring it so that we feel healthy and happy. That's kind of what I got from going through your book and just even the title. You know, look, the blue sky is so exciting when we see a beautiful blue sky. We get there's something energetically that changes with us, right? When it's clean, it's fresh, you know, after good rain and everything's restored and clean, you get this happy atmosphere thriving instead of surviving and trying to survive. So you know, that's why I love that, the optimism and we can't do it and we don't have to die doing it, you know, because I feel it. I remember when I moved, sorry for jumping in. I remember when I moved to Los Angeles for my first full-time job after college, I lived there for a year or so and one day in the winter, a storm blew through and it cleared out all the air and there was snow on the San Gabriel mountains and the mountains around the city and I walked out of my apartment and I thought, "Oh my gosh, this place is beautiful but you never see this because of the smog that fills the air from our cars primarily." So I love what you said, Lisa, the idea of clearing the air in blue skies is a visual way of feeling healthier about ourselves. COVID did this too, right? When we stopped driving our cars because of COVID, no one wants that or would wish that to return. But the air in cities like Los Angeles instantly got better. We saw, we did the kind of experiment they would never let scientists like me do, which is to tell people, "Just stay home and don't drive your cars for a while and let's see what happens." COVID did that and the evidence was clear that our fossil fuel use is, you know, is polluting our air and ultimately still killing too many of us. You know, because we've traveled, we still were traveling during COVID and obviously we had lockdown period and then we were pretty much alone on the road in the country and in parks. I can't even tell you how many parks we documented during COVID and there was very few people around and then also everyone was there. But at that time, places that are, you know, just scenic pull-offs, you know, on major roads, you could actually see the view. I remember being in Pennsylvania in the vineyards and being able to see all the way to Canada over the Lake Erie, you know? I don't know if it's always like that, but it was just, like, everything became very crystal clear and the roads, the turnouts, and Marga, I'm sorry, I know I've mentioned this before, but it was mind-blowing to me, they were all covered over with vegetation. There was no road. And we were like, "Well, we can't drive here." Like it's all home. The plants are happy. We don't want to drive over the plants. It's like, "Keep off the grass, man." I was like, "Don't drive over it." But everything was grown over and it was, you went in parks and it was just so peaceful and quiet. We were really spoiled doing that. And I mean, the facilities and everything were all closed off and everything, but there was just this moment of you could feel that the earth was happy, you know, not necessarily with COVID. We weren't all happy about that, but you could feel that restoration. You could feel the change and just it felt really clean. You know, now we're back with road construction and all those fumes and, you know, we need the road construction, obviously, but, you know, it is a whole different world being back on the road again. You know, my eyes don't like all the fumes, my eyes are really sensitive to all of it. And I don't remember having eyes that were, you know, watering or itchy or anything during COVID, but now they're back. So, you know, there's just weird things that your body tells you that this isn't healthy anymore. So I feel like that's part of it, you know, when we think about the atmosphere. The atmosphere sometimes, you know, in science, it feels so far away, yet at the same time the atmosphere is exactly what's all around us, right? It's right there. It's not this far away thing. You know, I remember in South Africa, you know, being close to when we lived there and it was, you know, we were all freaked out about what was going on in Australia, the whole in the ozone. And that we didn't, we fixed part of that. Didn't we as society come together for the ozone layer? So if we could do that, isn't that something we could be doing now? We did. The ozone hole in the Montreal Protocol to protect the ozone layer, in my view, is the most successful environmental agreement that's ever been forged. We saved, you know, millions of lives a year from that agreement. We still saved millions of lives. It saved an incredible amount of warming because CFCs are super potent greenhouse gases. I'd say people from skin cancer and cataracts, you know, billions of people are healthier because of that. In fact, the planet might not have been habitable, you know, this century if the ozone CSCUs had gone on unchecked. It's a terrific success story. It's a model for climate change, but it has some substantial differences. We were able to substitute one family of chemicals for another to solve the problem. And I think it's important to point out that the same companies that made the original chemicals were able to produce the new chemicals. So there wasn't this dynamic of one set of companies being put out of business potentially by a change in technology. The same companies were able to benefit from producing the new chemicals and make money from them. So it wasn't the opposition to change that we have today from the fossil fuel industry. That's interesting, isn't it? That we can morph and change, you know? And the fossil fuel industry can change up a little bit, too. I mean, you could go into solar, couldn't it? You know? Yeah, it could. I profile some companies in my book, it's important to keep the good examples front and center. I talk with students, I like to say that optimism is a muscle that we need to exercise, and the first homework assignment I give them every class is to go home and research things that are better today than they were 50 years ago. And that list is long, it's life expectancy, it's global poverty, it's better air and water quality. So lead levels dropping 96% in our children in the U.S. because we phased out lead gasoline and save trillions of dollars a year by doing it. And of course, it's the Clean Air Act, a bipartisan act that we still benefit from today and that has a 30-fold return on investment. So it saves lives, hundreds of thousands of lives a year at a great return on investment. So the success stories are out there, I think chronicling and keeping those success stories front and center in our minds makes it easier for us to see that we can succeed at climate change too. When you look at past problems that we've beaten, you think, okay, we can do this. It's harder, a lot harder than the Amazon hole, but it's not impossible. And holding, you know, our leadership, you know, holding them accountable too and pushing them, like, you know, voting and going to town hall meetings all the way up to the top, right? I think that's something that we can't, we get, you know, we can get, we look at politics today and everyone's arguing and upset and all of that. But like you're saying, if we keep the success stories, I mean, I look back, I mean, the, you know, Nixon side in the EPA, you know, so come on, and the Wild Horse Preservation Act. So you've got to think, you know, both sides of, you know, both parties, if you will, have been instrumental in protecting the planet. And I don't know anybody who doesn't not care about the future of our planet for themselves and for their families and for their, you know, children and future children. So it's coming together and really going, hey, what can we do and look at the success we have done and look at the changes we've made and because people don't like change. But the reality is climate is changing, but we can work together. I feel like, you know, it's, I love that you're saying that about the success stories. Don't you think so, Margot, too, that's so important to, to wave that flag, basically, you know, that we can make these positive changes? Right, I think that, you know, we, we're seeing now, or at least I'm seeing now because my eyes are searching for a success in, you know, people like yourself who are coming forward and showing the research, showing, you know, what's happening and what's working. And that's why we created this show. We want people to know that it can be done and that we want people to go and study, you know, like in your class, to study, you know, how can we make a change and, and, and document the changes that are happening. And I'm seeing one of my favorite shows is it's, it's about a farm, a woman who started a farm, a small farm for creating flowers, it's called florette. And she bought land that was destroyed by a large farm that had been there before. They really didn't even have nutrients in the soil. And she documents how they tried to, they not tried. They actually did turn it back into healthy soil, healthy farming activities and how nature start to come back and, and each layer of nature, each year something new would change. There'd be a little disruption and then there'd be another layer coming in like maybe in the first year they were, had trouble with pests, you know, the bugs and what have you. And, and the next year the birds came back because they had planted a lot more trees and they had, you know, so it's like step by step, we can bring this environment back and we can go by what you've presented in your book, how we can assist the atmosphere. And even, you know, you're talking about methane gas, methane gas is caused by, I believe an organisms, you know, that are breaking things down. And, you know, so in the healthy farm situation, you don't build up all those organisms. And so you aren't producing the excess methane gas and things are done differently and these people are showing how they're done so that we don't build up the excess methane gas. And, you know, I would like to know what your opinion is as to what our next steps should be kind of outlined for us, what can we do in our homes, what, what our country needs to do based on everything that you've researched and put out in this book. Yeah, thanks for the question. We started to touch on this earlier, but I like to think of the answer in what we can do individually and then what we need to do at a bigger picture sense, societally. And individually, the list is long. It's not a, the list isn't long enough for us to fix climate change on our own, but there's a lot we can do individually. And I start with the sources of the most pollution in our lives, our transportation, our cars, our homes, so we can choose to, you know, as we discussed before, we can choose to walk or I buy bike to work, we can take public transport. And if we have to drive, we can choose to drive a faster, cleaner EV than AM, than a gasoline powered car that releases carbon dioxide pollution and knocks and carbon monoxide and other pollutants into our air that still kill people. We can choose to power our homes with clean electricity instead of gas, you know, for our, I study a lot of people's gas stones. Stoves, I've been in hundreds of homes to measure the methane leakage from, from stoves while people cook and while they're off. But also the levels of benzene and, and knocks gases that gas stoves emit into our home, you would never stand over the tailpipe of a car breathing in the exhaust voluntarily. And yet we willingly stand over our stoves breathing the same gases in our homes and there's no catalytic converter for our stoves. So why do we choose to do that? Far the reason is because, you know, we've been taught to believe that gas is clean and it is clean if you're one of the billion people on earth still cooking over wood or dung in your home. But for the rest of us, gas is the dirtiest fuel that we use indoors and, and electricity is much cleaner and faster. So we can, we can make choices that reduce our emissions for our cars, our transportation. We can fly less. We can cook over cleaner fuels. We can reduce our beef and meat consumption, eat lower on the food chain, more plants, as you talked about earlier, Lisa, there are a whole, there are a whole family of things we can do individually. But then there is this other set of things that we can't fix on our own. We cannot produce green steel on our own. The needs, the industrial needs are too big. We can't produce clean cements on our own. So we need systemic change at the national and international levels. We need to pay for pollution more directly in Europe. The polluter pays in the United States. The polluter doesn't. So any technological pollution that you want to add on to something in the US is always going to be cheaper than free, right? It's always going to cost a bit more money. So we need carbon price, we need to pay for methane pollution, and we need systemic change. And in some cases, new regulations to incentivize cleaner fuels. Oh, see that it goes to that national, international level because it needs to, you know? That's why I always feel like we have our individual changes, but that we have to, how do we as society get that national and international change to happen, other than really going to our constituent, going to our parties, going to our politicians, no matter who our leadership is, right? Don't we have to write letters and just keep knocking on their door? That's, you know, for that kind of change? I think we do. I think that's the most important thing. I mean, you brought this up before, that voting and being active, voting for the environment, voting for clean air and clean water is as important, maybe even more important than the individual choices we make to reduce our own emissions. And I love what you said earlier, Lisa, you were talking about Nixon, who doesn't have the best environmental reputation or reputation of any kind, but he, you know, founded the EPA under his administration, initiated some clean air and clean water bills. One of my biggest regrets is the polarization and how political the environment has become. Ronald Reagan signed the Montreal Protocol for the ozone hole. That's right. George H.W. Bush signed the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change. So it wasn't always a one-party pro-environment, perceived one-party negative environment that many people feel like we are today. The Republican Party was a party that supported environmental legislation. And I wish we could get back to that place where the environment wasn't a one-party issue. Yeah. Because it's not going to survive that way. You know, it can't. Because again, aren't we unified in that we want clean air, clean water, fresh water? We want, you know, a positive future for our youth and for ourselves, you know? I think we can unify on that if we look at that. I mean, there were studies done about our national park system, about the, you know, popularity and need for them, you know, to have those protected areas for wilderness and recreation. And both parties came back, you know, with, you know, the 90-100% mark. You know, we were unified in that. So, you know, historically we have been and, you know, this polarization, this whole thing is it's not, it's not helping anything. And so I know that's, that's why we don't belong to a party unless there's champagne involved. But honestly, and it's true, but it is about issues. And so it's, you know, even if we get someone in as president that is not your choice, it doesn't mean you stop. You know, fighting for the environment, no matter who it is, you know, is to put the squeeze on them, be the squeaky wheel, but you don't need oil on it. So, yeah, no, very good. Rob, thank you so much for your time and for writing the book. And one thing is the other thing I want people to know into the clear blue sky, the path to restoring our atmosphere, you know, Rob may be a scientist, but it is a interesting read. And we can all do it. It's not a bunch of numbers that are going to freak us out. Yes, the evidence is there. Right, Rob? We can enjoy your book. I think that's right. I, it's, I, I hope that it's, it's accessible. I didn't write this book for, for scientific or an academic audience. I wrote it and told the stories in the book because I think everyone wants to see the world be better, that we all want to leave the world a better place for our kids. And I think every person, regardless of political party, believes that they're working to improve the world. And we just need to, to funnel or channel that energy towards cleaning up our air and fixing the climate problem and making ourselves healthy today. So yes, please, please do read the book. I think you'll enjoy it. And thank you so much for having me, Lisa and Margot. Thank you. Thank you. Thank you so much. Everyone, Rob Jackson, books.com is the website and the links in the episode notes as always. You can also link over to Margot Carrera as well from there and have a look at her beautiful photography and all her gifts from that. You can wrap yourself in nature, literally. Thank you so much, Margot. Thank you, Rob. Everyone, take care and let's do something for our planet today. Thank you for listening to Big Blend Radio's Nature Connection Show. Follow us at Big Blend Radio dot com and keep up with Margot at Margot Carrera dot Etsy dot com. and subscribe. (upbeat music)

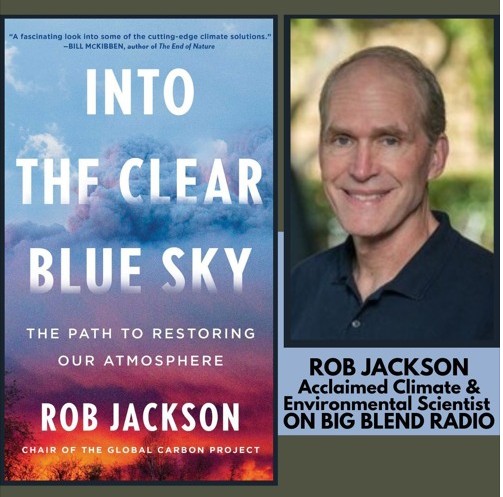

Scientist Rob Jackson discusses his book, ”Into the Clear Blue Sky: The Path to Restoring Our Atmosphere.”