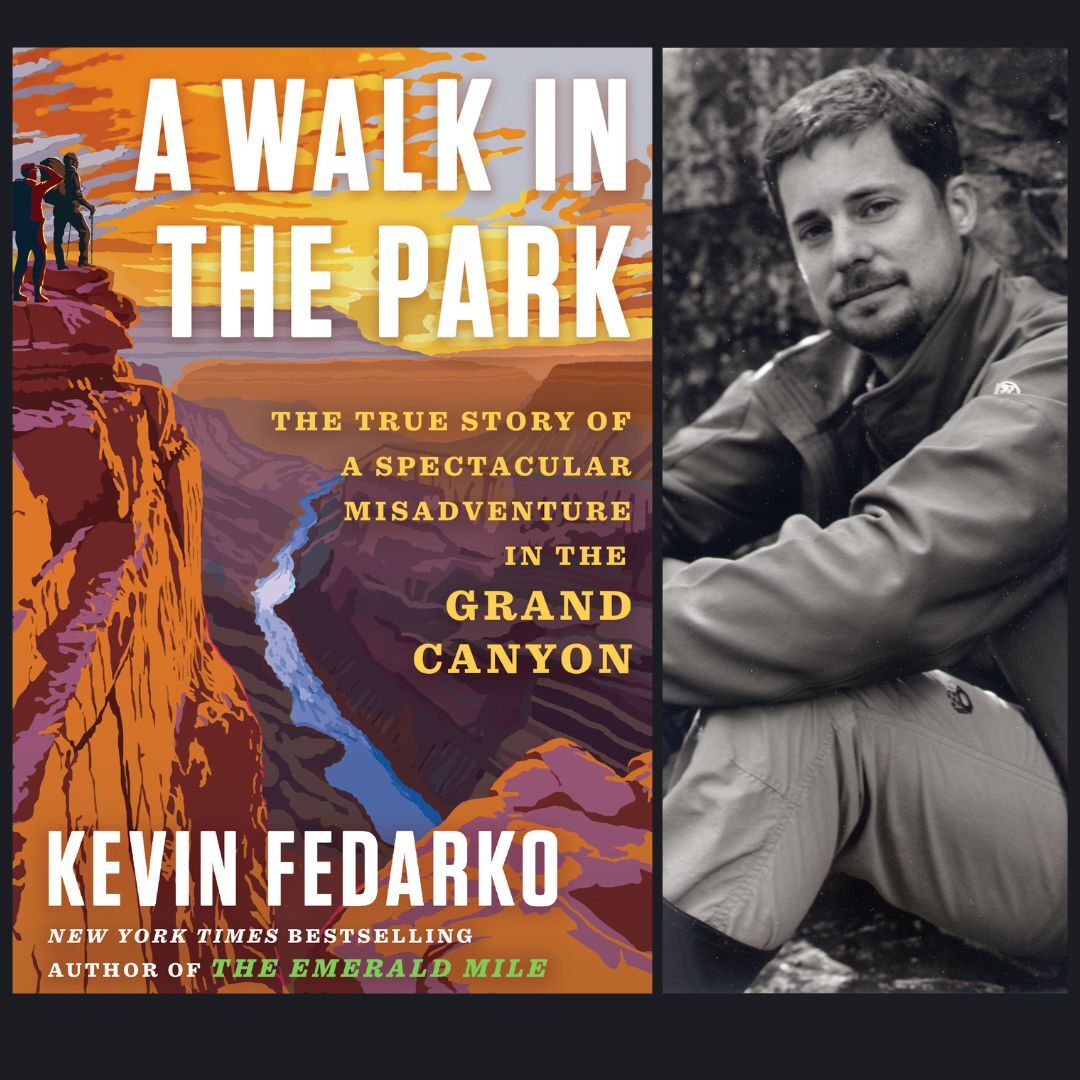

Welcome to Big Blend Radio's Parks and Travel podcast covering parks, public lands, and historic landmarks across America and around the world. Welcome everybody. Today we're excited to welcome Kevin Fedarko onto the show. He's an award-winning author. He's a writer. He's an outdoor adventure park lover. You may have heard of him from his book, The Emerald Isle. I was going to say The Emerald Isle. We're not going to Ireland today. Today we're going to go to the Grand Canyon. We're going to talk about his book A Walk in the Park. Now that sounds easy, right? Well, the subtitle is The True Story of a Spectacular Misadventure in the Grand Canyon. And it is out now. So go check it out wherever you get books and check it out at a local bookstore if you can. So welcome, Kevin. How are you? Hi, Lisa. Thanks so much for having me on. I'm doing great. Now the going, you guys, you and your good buddy decide to go on a walk across the Grand Canyon. It's kind of like Nancy and I saying, oh, we're just going to go on the road for a few years and do our parks, just national parks. And now like we're 12 years or something. We haven't gone home. So it's kind of, it's a lot of ups and downs. COVID comes in, but actually walking the Grand Canyon. Why? What led you guys to do that? I should probably begin by saying it wasn't my fault and it wasn't my idea. This is an idea that was brought to me by my good friend and long time collaborator, the National Geographic photographer and filmmaker Pete McBride. He and I have a, at this point, a kind of two decade long partnership that has taken us all over the world to all kinds of exotic places and gotten us in all of those places into more trouble than we ever should have gotten into largely because of his port preparation and inadequate homework in coming up with and conceiving these ideas. But none of them was more challenging or difficult or got us into more trouble than the idea that he came to me with in the summer of 2014. And the proposal was that the two of us embark on a journey along the length of Grand Canyon National Park, starting at least very in the east and moving all the way to the Grand Wash Cliffs in the west. And Grand Canyon National Park, as your listeners probably are aware, you know, is a magnificent park. It's the second most visited park. It's I think arguably, although not everyone may agree with this, I'm biased, but it's the most iconic of all of our national parks. And it's a park that has a highway that runs through the middle of it in the forms of the Colorado River, which is the Colorado River, which is the throughway through the Grand Canyon. It's what enabled the first traverse and recorded history in the summer of 1869 when John Wesley Powell, the one armed Civil War veteran and explorer, conducted the first traverse by boat. And it's the logical way to go through it. It's the only way that makes sense, but what he was proposing was something quite different. That we do this on foot by navigating through the matrix of cliffs and ledges that run along the walls of the chasm along both sides. And that is particularly hairbrained because as it happens, there's no trail that runs through this iconic second most visited national park in the country. So the proposition was rather dumb and deeply problematic. And the the the adventures and misadventures that we encountered along the way all arose from the fact that we were not going to float through the thing by boat, but move through it by putting one foot in front of the other and carrying everything we needed on our backs. Wow. And I want to just touch base on the fact that I don't think you can just legally do that without permits, right, or can you? You cannot. It's very important. There's a, as in many of the parks in Grand Canyon, in Grand Canyon, this is particularly true. It's very closely regulated by Grand Canyon National Park and the officials there. You need permits to conduct anything more than a one night hike at the Grand Canyon, and particularly in the sections of the canyon and involved moving through the back country, this very delicate, very fragile ecosystem inside of the canyon. There are a number of trails that can take you from the rims of the canyon to the bottom of the canyon. But for the most part, there are very few trails that will enable you to move laterally through the canyon. There is, along the south side of the canyon, there are trails that will enable you to move in a linear fashion along about 15% of the distance. And along the north side, which is even less heavily intrapped, there are trails that cover only about 5%. But the permitting can be challenging. And we never would have been able to undertake this trek had it not been for the fact that the park service and the superintendent at the time thought that it was important for this project to unfold. It was sponsored by National Geographic. It was intended as a informal inventory of the treasures and secrets that are hidden from many people who see the canyon either from the bottom along the river or from the rims, which is the way most of us travel to Grand Canyon National Park experience it. And they allowed this to go, this journey to take place because they felt it was important to showcase not only the hidden treasures and wonders, but also a number of development threats that loom over the landscape. And this was all conceived as a way of marking the celebration of the date that I'm sure is important for you and your listeners. It was 2016 was the 100th anniversary of the organic act, which brought the National Park service into being for the first time. You know, with the Grand Canyon, the topography is incredible because I look at the Colorado River, which we kind of followed, you know, from Rocky Mountain National Park all the way down to Yuma, Arizona, where the Yuma Crossing National Heritage River, Heritage Areas, which is it's like the lower Colorado River and they've done a lot of great restoration work. But, you know, the Colorado River, we've done so many interviews also about National Geographic scientists and things like that with what has been going on with the river. And it is so fascinating to see how the topography is with the way the water has gone through, the wind has gone through over the years, I mean, thousands, millions, just it's epic. And now, you know, to not a, it's so important that we understand that this is like the Nile of America to me. That's how I look at it. It's like the Nile. And without that river, so many communities are in dire straits. And I think we're still in dire straits with the water and, you know, the lack of water in the Colorado River. And then just even there's so many issues facing it, pollution, you know, on all levels, whether it's even from the air, that's one thing we're working on is to document sound for blind people and, you know, sight impaired people so that they have a way to experience parks if they are not able to go to them. And I think what you guys have done is so incredible because you're taking the park out of the park for people, especially when our parks are overrun with people. The big iconic parks are just facing so much damage of how many people can we actually have in a park. So you're giving this access that not people aren't going to be able to get permits for all the time. But through all that, you know, I'm getting a little negative, but I don't mean to be, but it is, I think it's a really important thing to bring up what our parks are facing, especially that region, the whole Colorado River Plateau is facing, you know, just climate change issues, pollution, everything we were talking about. But going through with this plateau, the river at the bottom, didn't you see all this change of habitat? I mean, if you even go to the Grand Canyon to the south, it's night and day different, you know what I mean? So that had to be pretty incredible to kind of see that web of life and then see also the perils that it's facing. Yeah, absolutely. I mean, one thing that a lot of people don't appreciate, including me before I really kind of immersed myself in the interior of the canyon is so many of us know that Grand Canyon is rather deep. This is a, this is a, this is a park, you know, transacted by a river that carved and polished and created and sculpted the canyon in the first place, the Colorado River, as you mentioned a moment ago. The river travels for 277 miles as it moves from Lee's Ferry in the east to the Grand Wash Cliffs in the west. And it is, it is framed by these mile high ramparts of rock, terraced systems of cliffs and ledges that rise, you know, really about 6,000 vertical feet at the deepest parts of it from the shores of the Colorado River on either side up to the rims of the canyon. And what that means is that there's this incredible variation and diversity of temperature and habitat and ecosystems that are arrayed in much like the layers of rock that comprise the walls of the canyon, they are arrayed in layers in strata. And those strata encompass so much variation that, you know, if you're moving from the highest points along the north rim of the Grand Canyon, you're looking at an ecosystem that is, you know, comprised of conifers and aspen trees and it's a very cool environment that, you know, can be under 6 to 8 feet or more of snow in the deepest parts of the winter. And then all the way down at the bottom of the canyon, you, you encounter a Mojave Desert ecosystem, you know, where you find plants like, you know, Choya cactus and acacia trees and creosote. And there is so much variation, Lisa, between those two points that a person who is walking from the north rim of the Grand Canyon, making their way all the way down to the bottom of the canyon will encounter the kind of variation that you would encounter. If you started walking in the tundra environment of central Canada, and major way, all the way to the Sonoran Deserts of northern Mexico, there are 2000 miles of habitat and ecosystems and plants and animals and flora and fauna that the Grand Canyon takes and it compresses all of that down into the space of one vertical mile, and then it flips it from the horizontal to the vertical. So the Grand Canyon does not, it does not command the kind of numbers that one sees in terms of speciation and animals in parks that you would find such as like, say, Great Smoking Mountains, right, where the calf skates. But in terms of scope and variety, what you find in Grand Canyon has as much diversity as any other national park anywhere else in the United States. It's a really remarkable place for that reason alone. And then what about the people of the park, which I think sometimes we forget about, and you know, more than not the touristy souvenir stuff, right? I'm talking about the people that have lived there for generations and generations throughout, right? So the park area, were you walking through areas where people made their homes? Yes, I mean, I'm assuming that you're talking about the people who are indigenous to the land, the Native American tribes, and I have to confess that this is something I'm ashamed and embarrassed to admit, you know, despite having worked as a river guide for six years, despite having written a previous book on Grand Canyon about the culture of the river, I had not taken the time or the trouble to really immerse myself in and learn about the indigenous tribes of Grand Canyon. And one of the great experiences that punctuates, in many ways, defines the story in this book, this book that has just come out, the story of the hike that P. McBride and I conducted, was that, you know, in many ways, Lisa, this is a, you know, it's a tale whose frame involves, you know, two middle-aged white guys bumbling through an extraordinarily beautiful and challenging landscape, but the heart and soul of this narrative are the Native tribes of the Grand Canyon. There are 11 Native American tribes whose ancestral lands either a butt or lie directly inside of Grand Canyon National Park. And, you know, one of the central aspects of this park, which is also a true of pretty much all of the rest of our parks, is that there is a kind of myth and a lie at the heart of this landscape. What we tell ourselves as Americans is that, you know, we demonstrated the wisdom and the sagacity to identify this beautiful piece of landscape and set aside and protected for future generations of Americans, and that when we, as the descendants of white Europeans, discovered this place in the 19th century, it was empty. This is not true. This is a place that was home to generations of tribal people for thousands of years, people whose knowledge of and connection to this landscape really dwarfs anything that somebody like me can embrace in the space of a single journey, much less a single lifetime. That wisdom, that understanding, that connection is encoded in the culture, the languages, and the traditions of these people. We forcibly and physically shoved them aside and exiled them from their homes. And then what we did after that is we wrote them out of the history and the stories that we tell us ourselves about this place. And so, the central aspect of this book is my effort to acknowledge and familiarize myself with this element of the landscape itself and the park and to make the argument that this is as important this layer of the canyon, this history is as important as any other aspect of it, the flora, the fauna, the geology, the hydrology, the meteorology, and re-enfranchising this part of the landscape into our understanding of it is something that's not just right and important to do. It is something that deeply enriches one's own experience. If one takes the time to learn about these people and even more importantly, to speak to them directly, which is what we were able to do along the course of our journey. That's amazing. And, you know, I look at, you know, what we do with our Love Your Park store, we're connected and our whole thing is about connecting community with the parks. And when we say community, it's the immediate community around a park within a park, right? And also the visiting community. And it's about, so it's our Love Your Park store, it's not about, don't love them to death. We've all heard about things like, you know, that kind of slang. But, so our parks are really facing some issues as we were saying in the beginning here. But when you look at the people, we always look at it. If the people are unhealthy, if the community of people is, they're unhealthy, that means the park is unhealthy. There is a connection between the human aspect and the natural area. And if you go to the indigenous people, they understand it more than anybody else can. I mean, we lived in Africa for many years. The bush in Kenya and South Africa did all kinds of park stuff. And I lived with two tribes as a kid, you know, and I'm going to tell you, they know, they know how to smell, they know how to taste the air, they know, they are just so embedded with how the landscape works, how the animals work, how the weather works, all of that. And it takes from, it's generational training. I think it becomes part of their DNA, you know? And so here comes the settlers, the explorers, the pioneers, and terrible things ensued. And at the same time, I don't think they quite got it. You can't get it all in a lifetime. I don't think we can, because these are generational stories. And just like birds come and fly and they roost in the same place, if they're on migration, that's their home. Whether or not we put a house there, that's their DNA, that's their home. And I feel like what you went through, it's, you're getting that connection about community and park that is so crucial, because again, if the community is not healthy, the park's not healthy, the park's not healthy, the community is definitely not healthy. And I think the Grand Canyon really shows that example with so many things that are affecting it, whether it's mining, and the uranium mining has been something I know that we fought for many years on our show and and affected the people. If it's affecting the people, doesn't that affect the actual land, the landscape, the animals, the vegetation, right? So can you tell us a little bit about that of going through there and seeing, I mean, that's, I'm getting so, so incensed about seeing, I don't, it's really hard to go anywhere without seeing telephone lines, electric lines, some kind of extraction going on in or around a park or a public land, airplanes, air pollution, I feel like there's more noise, it's very hard to do a recording of a bird. It's so hard and it's become this thing and still trash and pollution. So when you're out in the middle of the complete wilderness, were you able to find that Zen moment of peace and calm, pure wilderness away from all that? I mean, we were for often for long periods of this journey. I mean, partly by dint of the fact that there's not a trail that will carry you through and along the length of this, this huge park that six million people visit each and every year that there are enormous spaces within it that are defined by tranquility and stillness and silence. But, you know, to go back to what you were mentioning about the tribes a moment ago, the tribes are a very important part of the landscape, they're a very important part of the history. But, you know, I'm going to say something that's probably somewhat controversial that some of your listeners may not agree with or may be shocked by. But, you know, I mentioned that there are 11 Native American tribes who are connected to this one park and this one landscape and they do not all take the same approach or view or embrace the same set of values when it comes to respecting or protecting, I should say, protecting the landscape in a manner that preserves it as something pristine and they do not embrace the same set of values when it comes to an understanding of what good stewardship means. There are a number of development threats that hang over this park, including uranium mining, which you mentioned a moment ago. Many of the tribes stand in opposition to those projects. We encountered a project in the eastern part of the Grand Canyon that involved an effort by a group of entrepreneurs to build a huge resort and a tramway down the walls of the canyon. This is on the eastern rim of the canyon and a tramway that would be capable of delivering 10,000 people per day down to the bottom of the canyon and that part of the canyon, which was fiercely resisted by certain members of the Navajo Nation who succeeded in defeating that project, but it was also embraced by other members of the Navajo Nation who felt that this was an opportunity to provide jobs and prosperity in a section of the Navajo Nation, the largest reservation in the United States, a reservation roughly the size of West Virginia that experiences deep and lasting economic hardship along its western edge. And to give you another example, and this directly touches on your question about silence in the far western part of the Grand Canyon, we have another tribe, the Wallopi tribe, that's taken a very different approach. They have actually embraced industrialized tourism. They have constructed a building known as the Skywalk, which is, of course, glass bottom observation deck along the rim of the canyon inside a tributary, but along the rim, they have begun offering motorized boat tours along the river, directly beneath the Skywalk, and linking those two operations together, they have permitted hundreds of helicopter air tours to fly, to do something that's not possible anywhere else in Grand Canyon, which is to fly beneath the rims of the canyon along the river corridor, land next to the river, deposit tourists who can experience the bottom of the canyon without having taken a single step. And there are up to 500 flights a day that flood this part of the canyon. It's known as Helicopter Alley. It has had a massive impact on both the visual part of the canyon and the soundscape. It is impossible to experience extended moments of silence inside this part of the canyon because you are assaulted from dawn to dusk by the sound of aviation. And for someone like me to object to this, and I do, I am, I'm really kind of opposed to it, but for me to object to it is also for me to object to the fact that this operation has brought a level of prosperity to a tribe that has experienced profound economic hardship for 150 years. When I object to the sound of those helicopters, I'm also objecting to, I'm objecting to the scholarships that that money has provided that is enabled first generation of Walla Pie students to attend college and graduate school. I'm objecting to the emergency medical services and the programs for the elderly. I'm objecting to the fact that this is brought jobs on a reservation. For the first time, people are able to work in their communities and earn money living among their neighbors and not having to travel hundreds of miles to places like Tucson, Phoenix, Albuquerque and Denver to send money home. What I'm saying, I think, is that these are very, very complicated issues. The stance that the tribes take with respect to the land itself is not always uniform and deeply challenging to the sensibilities of someone like myself. Yeah, it's challenging for me, but because I'm just like, that's it. Stop anyone going in. That's it. It goes against even, that's not our thing, but we want people to go, but there's a respect level. There's a stewardship, but stewardship comes, it's growth. It's not just an overnight thing. It is in the DNA, but if we've messed with people, we messed with the Indigenous people in our history. We took away how their lifestyle was. All sides make sense, man, now I feel like I'm back in Africa. This is African politics. I think you're making such an important point for folks to understand that communities are going to be different on how they view things. Just because you're Native American doesn't mean you're all the same and all going to vote the same. Individuals are individuals. I think when you have not had prosperity and you need to go and do more than basic survival, stuff happens. There's a reckoning that has to come between communication of all agencies, which is hard. The Colorado River, you, my Arizona, really blew our minds. This was, we started covering that story about 20, 25 years ago when we first started our magazine out. We were out in Joshua Tree area San Diego and in Arizona. I think it was 49 agencies, including the Cachons. We also, I think it was the three different Native American tribes that got together with all these agencies, BLM land, MPS, everybody, cities, all of them got together, agricultural, all the water, all these people to reclaim the lower part of the Colorado River. But it took meeting after meeting time, I mean, to get everyone on board. That's not easy to have happen. But it, and as for the Grand Canyon, I do not see it being easy because again, you're looking at water, you're looking at tourism, you're looking at mining, you're looking at coal, riot, you're looking at all of that. So what would you say for those visiting the Grand Canyon and just kind of to keep our eyes open other than a selfie and don't fall down into the canyon, people, do you understand about falling down? It's just never fun. Well, one thing to kind of keep in mind and also responding to, you know, the points that you've just made and touching on, you know, what many people think is the essence of Grand Canyon. If you're lucky enough to travel to Northern Arizona and drive up through the entrance gate to the South Rim and, you know, stand on the edge of that abyss and gaze into it for the very first time, here's something, you know, that's kind of worth thinking about. And it speaks to the juxtaposition that exists within so many of our parks between wilderness and its opposite. You know, we think of, we like to think of our parks, our national parks as sacrosanct and inviolable, right? They were set aside and protected for all time. And of all the things we have to worry about, the one thing we don't have to worry about is our national parks being overrun by development or impaired in some way. But that's just simply not true. You know, each and every one of these parks is beset by all kinds of threats. And inside of each one of these parks, unfettered natural beauty and some form of development tend to coexist. And those two things come together inside of the Grand Canyon to something that you can see from the rim of the canyon, you stare down into it and you will see this thin ribbon of blue, the Colorado River flowing through the bottom of it. So this is the this is the instrument that created the Grand Canyon itself, right? The Colorado River carved and honed and polished and sculpted the Grand Canyon. And if you gaze on it from above, or you're lucky enough to ride some of the huge rapids in a boat along the bottom, it looks and feels unfettered and free. But it's not every drop of water that runs through the Grand Canyon in that river has been rationed and metered and engineered by virtue of the fact that it comes through a giant hydroelectric dam known as the Glen Canyon Dam that sits at the head of the Grand Canyon. And it will then filter through a second giant dam when it finishes its journey through the Grand Canyon, a dam known as Lake Mead, a dam dam known as the Hoover Dam, which makes up which which creates the reservoir known as Lake Mead. And those two dams that bookend and buttress, this national park are part of a balance of hydroelectric dams and reservoirs and water containment systems and irrigation networks that have shackled and controlled the entire Colorado River, this river that you referred to at the beginning of our conversation is the American Nile. It flows out of its headwaters in the Rocky Mountains. It flows through some of our most gorgeous parks, Rocky Mountain National Park, Canyonlands National Park, the Grand Canyon itself. But we have allocated and controlled and used that river so much that when it flows beyond Yuma, it doesn't even reach the sea anymore. The Colorado River, the ancestral Colorado River, flowed out of the mountains across the deserts and into the Sea of Cortez just across the Mexican border. And we use up so much of that water, the not a single teaspoon of the Colorado River, the thing that created the Grand Canyon in the first place reaches the sea. It's drilled to it trickles to a halt and dries up in the middle of the Sonoran Desert. So what you have when you go to a place like the Grand Canyon is the opportunity to contemplate those two things in relation to one another. We have controlled the thing that created the canyon so much that we killed it. And yet still this natural beauty prevails within it and conveys the impression at least of what raw unfettered natural beauty looks like. It's called the mighty Colorado River, right? They used to always say the mighty Colorado River. Well, it is and it is, but it's not. It is, but it's not. It once was, it still lives in parts, but it no longer is in whole. And what all of that offers us, anybody who goes to the edge of the canyon and stares into it, the opportunity to do is to contemplate, reflect on, and think about what we have decided to protect and save and pass along to future generations. What we have decided to sacrifice on the altar of progress and technology. And where we want to be as a society in relation to where we are now, now, in terms of the balance between those two things. Many people think of our national parks and I once did as places that we get to go into to have a vacation to escape from the complexities and the challenges of the world beyond the parks. And what I have discovered over and over again is that that is fundamentally not true. Our parks, our public lands, our beautiful spaces that we have protected provide the opportunity and the necessity of engaging in a heightened encounter with the complexities and the challenges that we face beyond their borders, not the opportunity to escape from them. And that is the difference between a vacation and a journey. And that is what these places offer each and every one of us. All we have to do is move to the edge of them, look into them, and start thinking. Yeah, it's not it's not a playground, you know, they talk about it always nature's playground. And the word recreation, I mean, we have recreation areas, right? For that reason, because it's about funding. It's about funding and to get votes to actually have these areas protected. You know, so much of our verbiage is for these, it's political, it's lobbying, right? And it's unfortunate. And I think that you make such a good point because it's unfortunate that we have to go to those extremes because those are the things that actually hurt in the long run. Absolutely. You know, it's it's so it's depressing. And, you know, for us on the tour, people are like, Oh, what's your favorite park? And I'm like, all of them. Now we cover everything from yes, the Grand Canyon, Yellowstone, all the way to a pocket park in a community, because we need green spaces for everything. We have dead zones, not just in the ocean, man, we have dead zones in our country. We have food deserts and dead zones. And if we don't do something, the parks are also a way to show us what could be and what isn't, you know? I don't want people to lose hope either. Do you feel that there's hope to help the Grand Canyon itself? And it can be a great example of what not to do and what to do for the rest of the country and world. I mean, you think about it. We started the National Parks Service. You know, I grew up in Africa. I always thought it was Africa who started until we got to this country. And I was like, Oh, really the Americans started this? You know, but so it's it's a little different for me. But do you what do you think about parks as an example? I mean, it should be a place of teaching stewardship to kids and to adults alike. Yeah, I mean, I think that this park, like all of our parks, offers hope and despair in the same breath. Yeah. I think that, you know, I think this is kind of important. I mean, I mentioned a moment ago that like this is the second most visited and single most iconic national park in our country. You know, it's the granddaddy of them all. It's the crown jewel. I happen to feel the deepest and most profound connection to this space because I've spent so much time in it. But, you know, one thing that I think is important to say is that it's not necessary to, you know, put a 55 pound backpack on your back and spend, you know, an entire year moving on a 750 mile journey through the heart of this park to touch and be touched by some of the most profound things that the canyon has to offer. It's enough simply to move up to the edge and move off to a space where you can experience a moment of silence and tranquility and spend time gazing into that landscape and taking in the stillness, the silence, the vastness, the perspective, just the gorgeousness of it all. It's enough to simply do that. And to that same extent, it's not necessary to go to the second most visited, single most iconic national park to understand why landscape matters and to experience profound national beauty. We have, it's enough to go to any park, the humblest of all of our parks, whatever that might be, has as much to offer as the grand canyon has to offer. All we need to do is move to them and connect to them. You can find that within your backyard, but it is necessary to move into that space, to experience silence and tranquility and to contemplate the wonder of it all. I can make an argument that the grand canyon is the most iconic and most important and granddaddy and crown jewel of the entire park system. And I feel like each and every person who listens to this broadcast has a connection to someplace out there. And they should be able to make the same argument. It's the greatest of all. It's the most profound of them all. And the reason for that is because they've taken the time and the trouble to connect to it, to show their kids what it's like, to bring their parents there, to go there not just once, but over and over again in layer, in much the same way that the rock is layered in the canyon, later layer memory, and experience in strata, so that when you return, you experience something rich and wonderful as you just think about the time that you have spent and the arc of your life and what that place is offered for you. So I make that argument with grand canyon, but anybody can make that case for any park in this country. All they need to do is connect to it. You know, hiking with your friend across, there's moments where you go, there's chat time and then there's a lot of introspect that happens when you hike and walk. You do connect. And there's a lot of headspace stuff that happens, right? You know, that it's, you know, with a friend who's passed and it sucks because he's awesome. He's a retired, was a retired earth science teacher and he hiked across the country, walked across this country as a retiree on the loosely following the American Discovery Trail. He's done majority of the Appalachian Trail. He's done the Pacific Crest Trail and then he also cycled the perimeter. But he talks about this headspace of keeping your keep going one foot forward. You're going to take two steps back, but you're going to take another foot forward. He had this mantra to keep going and to really absorb it. And before he passed, he had written a book called Walk's Far Man. And it was about the Native American heritage of the Pacific Crest Trail because he was tired of every hiking book telling, oh, turn here, do this. And he was like, do you actually know where you're walking on? Who's land? The stories? So you're going to do all the Native American tribes of, I mean, that's insane. But he did. So when you were walking, did you feel that too, about who was there and start to really get to understand the plants and have that connection of knowing this bird calls at this time? You know what I mean? There's just a connection. We really get that deep connection. If you listen and you look, there's, it's almost, I would say, spiritually moving, you know, if you can, everyone has a different word or whatever. But there's something, it's like an other sense that we forget that we have when we're in the city. But when you go out in these places, it's like you're, you have extra senses. Everything becomes more humbling and bigger at the beautiful at the same time. Yeah, one of the, I mentioned that, you know, we had a number of encounters with tribal members, Native Americans. One woman we met was a woman named Diana, Diana Sue White of Yukwala. She's a member of the Have a Supi tribe. And she, when we met with her, she gave each of us these little leather pouches that had some tobacco in them. And she instructed us to, she told us that whenever we woke up in the morning, we should rub our hands with sage leaves and then room it over our faces. And that way, the land would come to recognize that we were there. And then she instructed us when we reached a spring or a perennial stream. And there were very few of them in the canyon to take out a pinch of tobacco and sprinkle it as a, as a gesture of thanks. And she explained that this would be our armor and our protection. And I kind of said, really, do we need armor and protection as we moves through this place? And she said, yes, she will, because what you have space you're moving through is our home. And then she went on to say, she had another piece of advice. She said, she said that, you know, this is a very powerful journey that you're on. But in order to hear what the canyon is trying to tell you, in order to be transformed by the journey, you are going to have to pay attention. And you have to pay attention to the small things, the little things, the bird flying by in the morning, for example, or the sound of the wind. And that these are the things that if you listen hard enough and you pay attention with enough respect, you will come to understand one of the most fundamental truths of the landscape, which is that everything down there, everything that you encounter, the plants and the animals, of course, but, you know, the wind, the light, and even the rock itself, it is our belief, it is that have a supine belief that all of it, all of it is alive. And that is one of the things that she wanted us to understand. And we did. I think, I mean, we were a couple of white guys, so, you know, we're clueless on a lot of different levels, but there were moments when I think we remembered her words and were able to connect with these ideas that she shared with us and appreciate the truth that resides at the heart of them. That's special. Well, thank you so much. I could talk to you all day long about these things and parks and connecting with nature and land. I think that's that is a beauty of people going. And like what you're saying, take that time and moment because the more we connect, the more we will protect, I think. So thank you so much, everyone. Go to your bookstore online or your favorite shop. Get a walk in the park, the true story of a spectacular misadventure in the Grand Canyon. You'll be able to read all the shenanigans that happened on those that hike across because it wasn't easy. So you know things ensued. Again, it's by Kevin Fadarco. Thank you so much. Lisa, it's been such a pleasure. Thank you so much. And thank you for the work you do on behalf of parks. Oh, thank you. It's a joy. Thanks for joining us here on Big Blend Radio's Parks and Travel podcast. Visit nationalparktraveling.com to plan your next park adventure and to see our Parks and Travel digital magazine. You can keep up with our shows at bigblendradio.com.

Author Kevin Fedarko discusses his book, ”A WALK IN THE PARK: The True Story of a Spectacular Misadventure in the Grand Canyon.”