Guru Viking Podcast

Ep262: Life of Liberation - Dorje

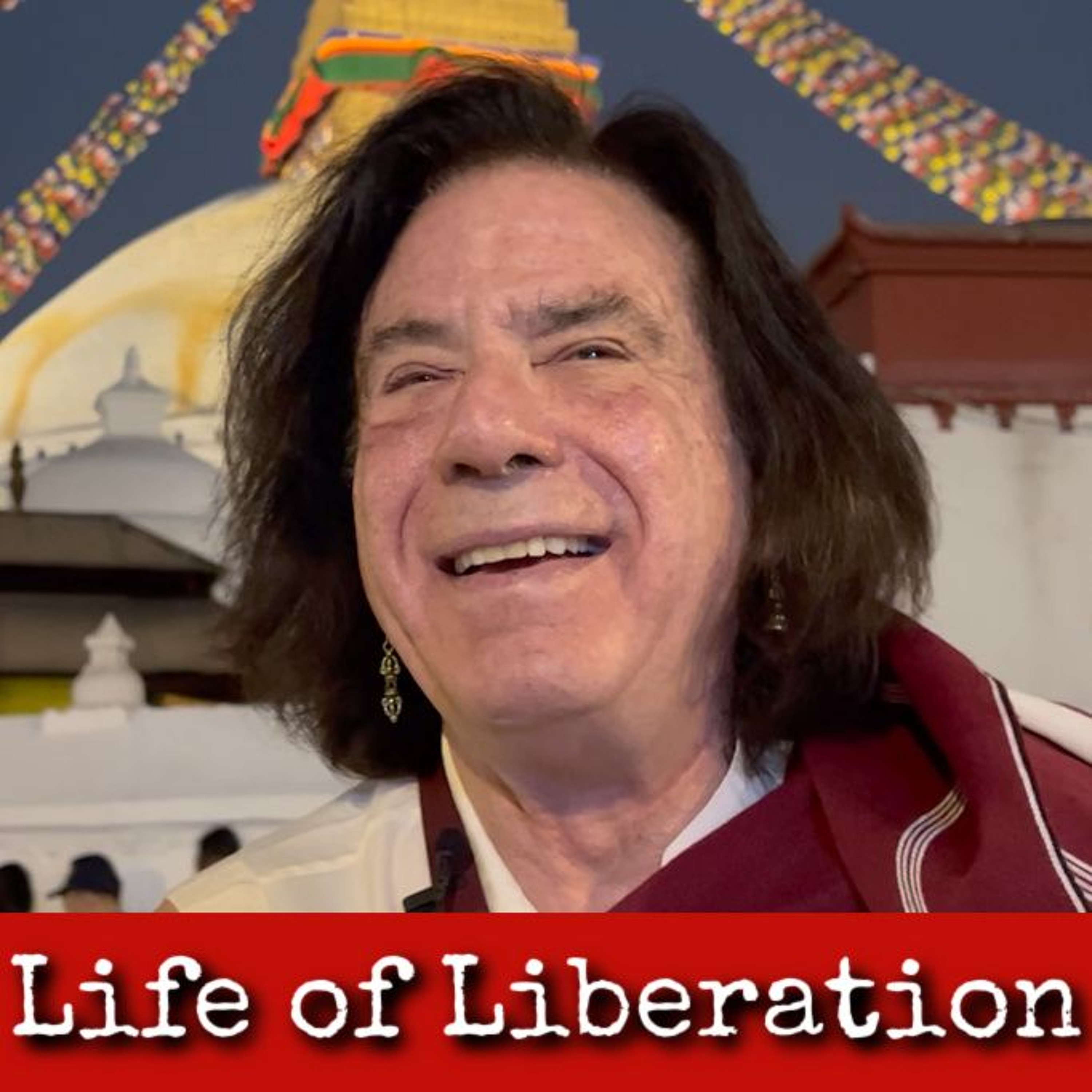

In this episode, filmed on location in Boudhanath, Kathmandu, I am joined by Dorje, an American Vajrayana practitioner born in 1947.

Dorje recounts his childhood in the American South, his move to San Francisco in 1968, and his involvement in the early days of the gay liberation movement. He recalls the arrival of AIDS in 1981, the traumatic deaths of his close friends, and the impact of his own HIV diagnosis.

Dorje explains his conversion to Buddhism in the midst of a chaotic and stressful life, his 25 years as an ordained monk, the power of Yamantaka practice, and his understanding of the spiritual path.

Dorje also explores the deep relevance of the core teachings of Buddhism to his experience of the AIDS crisis, describes the rhythms of grief and death, and shares what he has learned about helping the dying.

…

Video version: https://www.guruviking.com/podcast/ep262-life-of-liberation-dorje

Also available on Youtube, iTunes, & Spotify – search ‘Guru Viking Podcast’.

…

Topics include:

00:00 - Intro

01:03 - Dorje’s upbringing

02:07 - Dorje as a boy

02:59 - Career aspirations and becoming a lawyer

04:16 - Arriving in San Francisco in 1968

04:38 - Involvement in the civil rights movement

06:28 Early days of the gay liberation movement

09:13 - The Cockettes

11:48 - Gay political organising in Atlanta

14:02 - Arrival of AIDS in 1981

15:21 - Deaths of Dorje’s close friends

16:10 - Dorje’s HIV diagnosis

16:45 - Stages of grief

18:50 - Dorje’s HIV related legal and political work

20:39 - Activism vs realpolitik

23:06 - Encountering Buddhism

25:08 - Reading DT Suzuki and Evans-Wentz

25:46 - Shamata in a highly stressful of life

28:29 - Drawn to Tibetan Buddhism

30:39 - The life of the Buddha

33:57 - Modern insulation from sickness and death

36:14 - The Buddha’s quest for enlightenment

39:18 - 4 noble truths and the core of Buddhism

42:26 - How to develop wisdom

44:10 - The spiritual path

47:38 - Ordaining as a Buddhist monk

52:12 - The 3 jewels of refuge

54:05 - Challenges of living as a monk

56:14 - Moving to Nepal

57:48 - Why were some people slow to recognise the danger of HIV

01:02:25 - Helping the dying

01:03:27 - The rhythm of grief

01:06:43 - Actors and magicians

01:08:42 - Facing his own death

01:10:01 - The power of Yamantaka practice

01:12:10 - Living with an HIV diagnosis

01:17:06 - Leaving monasticism and solo retreat during Covid

01:19:28 - Aspiration to help those newly diagnosed with HIV

01:23:19 - How to help those with a new diagnosis

01:24:10 - Side effects of medication

01:25:31 - Climate change in Kathmandu

01:25:42 - Hippy trail and changing fashions

01:26:35 - Experimentation with psychedelics

01:27:51 - Unsung heroes of civil rights

01:28:53 - Dorje’s Great Stupa kora practice

01:30:07 - Compassion and the goal of practice

01:31:33 - Kora around the Great Stupa

01:32:34 - Developing compassion for others

…

Boudhanath Interviews playlist:

- https://youtube.com/playlist?list=PLlkzlKFgdknwvU82dU487LhF_mF4AkGek&si=gFGJpi-fnLtxeyZ5

…

For more interviews, videos, and more visit:

- www.guruviking.com

Music ‘Deva Dasi’ by Steve James

- Duration:

- 1h 37m

- Broadcast on:

- 12 Jul 2024

- Audio Format:

- mp3

In this episode, filmed on location in Boda Katmandu, I am joined by Dorje, an American Vajrayana practitioner born in 1947. Dorje recounts his childhood in the American South, his move to San Francisco in 1968, and his involvement in the early days of the Gay Liberation Movement. He recalls the arrival of AIDS in 1981, the traumatic deaths of his close friends, and the impact of his own HIV diagnosis. Dorje explains his conversion to Buddhism in the midst of a chaotic and stressful life, his 25 years as an ordained monk, the power of the Yamantaka practice, and his understanding of the spiritual path. Dorje also explores the deep relevance of the core teachings of Buddhism to his experience of the AIDS crisis, describes the rhythms of grief and death, and shares what he has learned about helping the dying. So without further ado, Dorje. Dorje, I'm curious if you can say something about the context of your upbringing. Oh, well, I'm from the south. Grippen in a small town in Mississippi where my family had been for quite some time. And we moved to Atlanta when I was a child, which was quite different. And I grew up in Atlanta as much as I did. And what did you have, how can I put it? What was the economic situation of your family at that time? Comfortable. We lived in the suburbs, the very edge of the suburbs. Atlanta was growing. It's still growing. But for example, the high school that I went to, about half the kids were suburbanites like me, and the other half were from families that lived there for a very, very long time. It was a mix, a folk. And what sort of a boy were you, if we could peer back in time? What sort of boy? What were your interests and what was your character and personality like in those days? I was bookish, I was good at school. I studied a lot, enjoyed that. I was rather a proto-hippie, I guess you would say. I was a, me and a few of my friends were the first to say, listen to folk music like Bob Dylan and Turned By as and so on, this was in the early-to-mid '60s. When were you born, when were you born? '47, yes, at the beginning of the baby boom. And how did you think your life was going to go in those days, if we were to talk to the boy or the teenager, what ideas would he have had about how your life would have gone? That's a great question. I don't remember really, although I do remember being not terribly enthused about the potentials, the options that seem to be available at the time. Which way? To your mind. Doctor Lawyer, sales, marketing, corporation, corporate work, and so on, not the kind of thing that grabs a teenager. But interestingly, I wound up being a lawyer anyhow. Yeah. And further, I remember exactly when, I took one of those aptitude tests when I was in high school, and it said I should be a minister, and I thought that was completely ridiculous at the time, and here I am. So tell me about the law you practiced. You went to college, I guess, and qualified and so on. Well, there's more before that. I went to San Francisco in '68 because that's what everybody did. Then I arrived at my 21st birthday, I traveled across the country with some friends, my brother. They went back, and I stayed for seven or eight years. I got very involved in politics. I had been involved in, I wouldn't look out, in movement politics at the time. The anti-war movement, the civil rights movement, Atlanta was sort of the hub of the civil rights movement. People would come through on the way from the north to go out to the country to do voter registration or whatnot, and they would return shellshocks. It wasn't at all what these four Yankees students were expecting. In several different ways, in some ways it was better than what they thought, in some ways it was much worse, but anyway, I was involved with SNCC, student non-violence coordinating committee, and later on SOC, Southern Students Organizing Committee, which was white people were kind of encouraged to get out of SNCC, and so many of them went there. Then the anti-war movement happened, I was quite involved with that. It affected me almost directly, so many of my friends were either being drafted or trying to get out of the draft, and my brother too. When I came to San Francisco, I came out, obviously I oozed out because at the time it was -- all the stereotypes that identities were something that people wanted to avoid, and we were all -- the guys at the time was to develop your own identity, your own genius, your own creativity or whatever it is, and so identifying as anything was kind of not encouraged. That was the beginning of the gay liberation movement. I got involved actually shortly before Stonewall, there was a -- well, Stonewall, which happened in '69, I go away in June of '69, was a riot in New York when gay people fought back, gay men fought back, and trans people, drag queens as they were called in, fought back when the police raided a bar, and that's reckoned to be at the beginning of the modern gay movement. However, for those of us in California, we would take issue with that since there were so many things going on there, but like they say in California these days, Stonewall wasn't the wave. It was the crest of the wave, but it wasn't the wave that had already been a riot of street drag queens, there had been a friend of mine had been -- far from his job with a steamship company for being gay, and that became a cause to labor, got a lot of media attention. There was an incident in LA that got a lot of attention to the -- which one of the editors or economists in one of the newspapers mentioned something homophobic, and so we all went down there to protest and had a little picket line and so on, and the printers were up on the roof, and they started pouring lavender incontus, and so we put our hands in the ink and pressed it against the well, so they remember our handprints all up and down the wall, and that kind of became a symbol for the gay movement for a while, at least in San Francisco, replaced by many other things, like the big triangle now, the rainbow flag, so it was quite heady. It was something that I'd never done before, that nobody ever done before, and we -- the first folks who were really accepting of us was the left, and they kind of struggled with it a lot. We had a gay contingent in one of the massive anti-war demonstrations, the ones that were 100,000 people that were among the first really big ones, and that was new. Nobody really knew quite what to make of it. Some people thought it was a lifestyle thing, and not really -- along the lines of a discrete oppressed minority, like black folks, or like people in colonialist countries and so on, but finally, slowly, slowly, things got more accepting, and personally, it was -- there were so many things like that going on. Probably the one that was most interesting was something called the cockets. It was a -- a theater group that kind of started spontaneously with people just dressing up at whatever they had. The story that they like to tell is that in San Francisco, they performed at midnight at the Palace Theater on Saturdays, Fridays and Saturdays, I think it was, when they had a midnight showing. And the Palace Theater was also the place where the Chinese Afro was performed when they came to town, and so there was a trunk there full of costumes that somehow or another disappeared, and the product was a cockett production of Madam Butterfly in one of the alleys in Chinatown. The Chinese just cracked up, they thought it was hilarious. So it sort of came out of the street theater, the girl theater that was also happening then, and I was involved with them for quite a bit while trying to go to art school at the same time. One of the most interesting things that have it, or the most high-profile thing that happened was when it was announced that Tricia Nixon, President Nixon's daughter was going to be married, that day the decision was made to make a movie of the wedding that premiered on the day that she was married on Tricia's wedding, and of course she was played by a six foot three drag queen, and so on, it was fun. It was not professional at all, but people loved it. I mean, Google it's, a documentary was done, showing its Sundance did well, maybe 20 years ago I think. So that was a long time ago, that was 50 years ago. The cockhats were thought to be important because they sort of paved the way for a number of things. One was glitter rock, another was the way drag has been mainstreamed. There was never really outrageous drag like that before, drag that shot, drag that made a statement of some kind, that took on popular culture and kind of supported it with, yeah, make a long story short. So that's what I did, and I got a degree in film and photography at San Francisco Art Institute, I went back to Atlanta. Not much was happening then, so I kind of decided to make things happen, and got very involved in doing a lot of gay political organizing or less being gay political organizing as it was called in, and there were, I served a couple of organizations, probably the one that was most successful was one that started out as a gay democratic group, that we tried to be affiliated with the Democratic Party, they didn't want us, but so that didn't matter. We went off on our own anyhow. It was the first to try to get out the gay vote, to try to build a gay vote, we do that with candidates forums, and interviewing the candidates, and endorsing and supporting candidates. And that's how pretty much how I spent the next few years, as well as practicing law. There were some other organizations too, like a gay center and a few other things, but that was my main focus, and that was, basically I learned that if you eat enough rubber chicken dinners, and if you support enough candidates and campaigns, then after a while you can go back and ask them to do something, and they'll do it, like say, passive, lantis, anti-discrimination ordinances, or have it amended so they're included sexual orientation, and also a lot of the general assembly or state legislature on AIDS issues when it came along. When AIDS came, I was a better serve a gay newspaper, called the Gazette in Atlanta, weekly giveaway, and so I kind of was more aware of it than most people were, since I was, you know, in a place to get all the national news, and otherwise, can I take a- Of course, Sam. So when AIDS came, in '81, I think it was, I was, nobody, I was among the very first to realize that it was awful, at least the first in my circle, and not just that it was going to be awful, but that it was going to be horrible, since I remember very well sitting down with the pocket calculator, and the number of cases or deaths, I don't remember, which was doubling every six months, I believe it was, and so I figured out that by the early 90s, hundreds of thousands of gay men would be dead, and that came to pass, but nobody really wanted to believe it, not in the gay community, and straight folks were not that interested. I felt like that Trojan Prince's name, Cassandra, who was given the gift of prophecy, I think by Apollo, and she could see the future, and however one of the other gods, maybe Hera, had it in for it, didn't like her, so she couldn't take away the gift of prophecy, but she made her know the curse, so that no one would believe her, that's what it was like, that's exactly what it was like, and it was awful, and then it got closer and closer, that is, I knew that one of the very first people to get in Atlanta to get sick and die, he was a bartender, and we would have dated, except he didn't get off to work it until 4 a.m. when the bars closed, so that kind of left that out, so he was a good friend, he died, and eventually all of my friends, my close friends died, except for one, and so I have no old gay male friends except for him, everybody else died, which was, it's really hard to, words, I don't have the words for what it was like, maybe other people do, but I was diagnosed in '85, it was shortly after the test came out, you just, and you get to a place that's beyond hope, and that's beyond despair, that stays with you, you become aware of one's own mortality, and the inevitability of death, and change, so I was practicing law by that time, and was the first lawyer in Atlanta who would have, who did much with HIV/AIDS related legal work, which covered the waterfront, not just wills in the states, anti-discrimination, and insurance, and healthcare issues, and property issues, and so on, and yeah, so it was quite, hmm, quite something, quite stressful, you know, Elizabeth Kubler Ross outlined these five issues that happen when we die, or when we think we're going to die, and, or when a loved one dies, or when we have any kind of loss, like a handicap where we're losing a job, and that became really clear, on a huge societal level, that is, people in the gay community were just, it became so clear to me, but not others, of course they're denial, and which would manifest as someone having a perfect anti-discrimination case, complete with a smoking gun, everything in writing, but they would say, no, I wasn't discriminated against, like they say, I was fired because of this, this, this, this, and these people really aren't treating you this way, when they were, in anger, people were quite angry, and some, I had a client who were like, every few weeks he would come in and change his will, because he was angry with some relative or another, and was leaving his salt and pepper shaker collection to this person, that person, I kind of, I finally had to start charging for it a lot, and then, there's bargaining, some people say, these come, these are phases that people go through, but I don't really think it's that way, others say it's not, and I agree with them, they're, they're these five issues that people sort of live in, and I think we bring to it whatever it is that we have, and my thing that I was bringing to it was bargaining, and that work, that's what lobbying is about, what doing politics is about, it's, yeah, so I love it, our general is similar, our state legislation or HIV/AIDS related legislation, in the mid to late 80s, mostly, and it was, a lot of it was trying to kill a really bad legislation that was ill thought out, since AIDS paranoia was at its high thin, and Georgia is not the most progressive of states, so some really bad things were scuttled, like mandatory testing for everybody, who, not everybody, but people say, who were arrested for anything sex related, people who were getting married, pregnant women, and so on, the right to life ladies became my friends with that one because of course, I went to the message, you know, if these women are pregnant, they're just going to kill those babies, and they agree with me, and these are kind of helping to do a few things with it, but politics is like that, that is, they say it makes strange bedfellows, and it's certainly true, and one tends to stay focused on whatever it is that you're doing, because in a legislature, there's this, there's a seamless web of alliances and adversaries, there's always shifting, and depending on the issue, you kind of have to know what's going on all the time, and focus, and make, if you're going to get your legislation killed or some bad ones killed or get some money appropriated, and that was, that's all that you do, so it was during that time that my fervor, the useful fervor, kind of went by the, by the boards, that is, I was quite a passionate activist, but as I got more involved in what I call real politics, rail politic, you, you just wind up working, having to work with people who are very different from you, and setting aside your, your differences to work on common goals, and you kind of set aside all sorts of things, I wouldn't say I became a hard gun, but I became much more cerebral and very, well, one of my friends said that someone who was a lobbied with another, an organization, she said I was one of the most relentless people there, and what she meant was ruthless, and she mentored as a compliment, I excuse myself because you see, in politics there are two things that really matter, one is votes and one is money, and it's good to have both of them, but having one is kind of necessary, we hadn't either, I had nothing but my brain, and I did whatever I could, and that's probably the part of my pre, Buddhist pre-month life that I am proudest of because I feel like I might have a greater contribution doing that than anything else, Iran for office, I was the first openly gay person to run for any political office in Georgia, and Iran for the State House, and a county-wide seat that was encompassed of a vast number of people, mostly Iran because I'd always wanted to, and I wanted to do it before I got sick, as I thought would be inevitable, and also I wanted to see, be able to demonstrate where there was a gay vote, and to be able to show folk the printouts, and say we're here, we're here, and so on, so those two things were Iran, Iran, I didn't win, and it's probably just as well since I'm ill-suited for, I don't have the temperament to be a Buddhist mentor, I was more of an activist always, and so, Bitter Dormer came along about that time in a couple of ways, one is being focused with one point in concentration on your piece of legislation that you're getting through, and kind of, not just, well, you have to know if possible about everything anybody else is doing, because that could impact you, or say for example, you have to know what's important to the various legislators like, such as agriculture, forestry, education, healthcare, you have to know these things, and you have to know what bills are up, and import it to them at the time, and so, but you can easily get distracted, and get off of somebody else's agenda. So learning how to focus was it, and at the end of the day, what you have, you either, you get money appropriated, or you kill bad bills, or you get good bills passed, and that's it, that's all you do, and it's quite rewarding, but it's kind of at a core of taste, it's the kind of thing that you kind of lie in bed at night and chuckle to yourself and think how clever you are, or it's, those folks who do that, the progressive advocates are some of the greatest unsung heroes, along with progressive lawyers, especially in the South, who kind of implemented all of the civil rights legislation that was passed in the early 60s, the great society, the Voting Rights Act, and so on, I practiced with a law firm with those folks, there were kind of a generation older than me, and I had learned a lot from them, they were my idols, my mentors, my heroes, they went on, some of them, it was a wild and crazy group of folk, it was a legal collective in the early 80s, so I got into a bit of Dharma then, I read it, a lot of it when I was a teenager, especially what was available, that is to say, D.T., Suzuki, and Evans Wentz, who kind of, well there have been better translations and better explanations of the Dharma since then, more accurate, but that's what was available, and I ate it up, along with Carawak and Burroughs, and John Chine and other things that she knew it was a reading back then, so when AIDS came, nothing else really made sense, that is, there were, I didn't find any consolation in Christianity of course, because most, the ministers there were saying that AIDS was God's punishment, homosexuality, ignoring the fact that lesbians almost never get it sexually, and I'd be happy to be a lesbian, but I just don't have the fixtures for it, so God punished me according to these folk, and the other religions weren't really, didn't really speak to me, but with the Buddha Dharma, there were two things that worked, one was the way that the philosophical aspect, one was the practical aspect, that is, meditation, my life was a mess, it was like being in the middle of a hurricane, a storm that was raging, everybody was dying, I was gonna die, I thought, I've never been sick from HIV only once, and that was a cancer that I got over, unlike most of my friends, so meditating shamata was the first one that we do in the Buddha Dharma, was like creating a little eye in the middle of the hurricane, and it spread and spread and spread, and for me, after a few weeks of doing it, I noticed how it was affecting my off-the-cushion life, or my post-meditative life, my work, that is, as I said, being a returning is quite stressful, doing advocacy for HIV, AIDS-related and gay issues too, and a deeply homophobic and AIDS-phobic culture, was rather stressful also, but nonetheless, it helped me a lot just to chill out and to take a look at things, and not to identify so much with what I was doing, which was a good thing, because one of the mistakes that a lot of people make, like me, when one's an advocate, or one is an enthusiastic, true believer, when you get involved in something like that, it can work against you, that is, it clouds your vision, clouds your thinking, and so you have to step back and take, as I said, take into consideration everything is going on, play it as it is. So that's, yeah, Buddha Dharma work, there was only one thing going on in Atlanta at the time, or two things, one was a Soto's In Center, and the other was Shambhala, a trigger in Trump as an organization. So I went to those for a while, and then a Gallupa group came to town and started an organization that's flourishing from, draped from the listening monastery, and I really liked that because it was a real deal, they were monks who were, they were gashais, there were others who were very well educated, very experienced monks, and also a thing about Tibetan Buddhism that I liked a lot was that it, in Buddhism, in the West when some new movement comes along, a lot of it is about refuting what came before, and the emphasis is on separating yourself from whatever came before, such as Christianity and Judaism, and the conflicts are obvious, or Protestantism and Catholicism, and so on, but in Buddhism, when we take a more holistic approach, there were three major branches of Buddhism, the first was, it's called Hana Yana, and we still practice it in the Tibetan tradition, so each one builds on the other, and the notion is that yes, that's true and good, but there's more to it, and so more to it comes along. Of course, in my Hana, it focuses, said to me more on compassion, and then in Vajrayana, the third one, or Tibetan Buddhism, it's on transformation, a lot of it is about transforming, suffering, transforming our afflictive emotions into something that's working for us, so each one of them is necessary too, and I like that a lot, so the Tibetan Buddhist appeal to me quite a bit. On a different level, what resonated with me was the story of the Buddha, and how he was a prince, and it was predicted that, well, for all of you watching this, I'm sure you've heard this before, but think of it as a review, he lived in what's now in Nepal, or was born in what's now in Nepal, grew up in what's now in India, and when he was born, a prophecy was made that he would either be a chakra gardener, ruler of the world, or he would be a great sage, and his father, of course, wanted him to follow him and to be a chakra gardener, ruler of the world, a greater king than he was, so he made his life pleasant. He had three palaces for each of the three seasons in India. He had music, he'd never knew suffering. He, when it came time for him to marry all the most beautiful women in the country, would call forth and he chose one, and then the story goes, one day he heard one of the women in the palace singing a sad song about her homeland, her country, and this surprised him, since he didn't know about sadness, and he asked him, and intrigued him, he wanted to know more, and he asked the various people, and he wound up going out with his chariots here, sneaking out of the palace, and were the chariots here, and he was a little more worldly than the Buddha, or Shakyama, sit hard as he was then before he became the Buddha, but they came to a person who was sick, and covered with sores, and shivering, and had never seen this before, because whenever anybody, or anybody in the palace in the entourage of the court got sick, they were either taken away or they were cured, so he never saw it. So he asked the chariot to hear what was happening, and the chariot to explain to him that people and animals can, everybody can, or can get sick, so he pondered this, he had never known it before, then went back to the palace, they went out again a few weeks later after the Buddha was, became more curious again, and they came across the corpse lying by the side of the road, and he was totally baffled, he had never seen a corpse, he knew nothing of death, so he asked the chariot to hear what was going on, and the chariot to hear had to explain to him that this was something that was no longer alive, that had been, and even though it looked like a human, it had been a human, a living, breathing, conscious human who lost no more, and the Buddha was shocked and surprised and didn't understand, and he asked the chariot to hear if that would happen to his father, and to hear if he was inevitably, and to his wife, and to his son, and to him, and the fact that he would die was quite a surprise, and I think a lot of us in the West, in America, are in that situation that is, when people get sick, I mean here in Nepal, if you look around, you'll see people with all kinds of injuries missing limbs, blind folk, or deaf youth, things that could, in the West, be very easily fixed before they became a problem, of course mortality rates much higher here, much more sickness here, we don't see that, we don't have that, when we do, we'll whisk away and put it in a nice, comfortable hospital if it's bad, so on, and we don't see death either, not like here, where it's a part of life, that is, here sometimes see people carrying the body of a relative to the cremation grounds, over at Pashapati or other places, chanting "ROMROM ROM ROM," and the eldest son, plays her in a porta park and the cremation that hits the top of the skull so that the hot run of the soul can be released, so it's kind of a visceral part of life here, unlike America, where we don't really seek corpses or dead folk until, unless they're, you know, they're looking beautiful, lying in their coffin. Evelyn Watt, in one of his books, the loved one that was made into a movie, he has a point, a poet in the right a poem about his deceased uncle, and he says, "And here you are, made up like a whore." So, yeah, so that's kind of what it's like, lots and lots and lots of things that we don't see or disguise, and they're whisk away and buried or cremated, and that's that, not like here, where we know we're intimately familiar with mortality, with sickness, with misfortune, like that, the poverty, and that sort of suffering. As it was in the Buddhist time, only, of course, the Buddha, or the Shakimini, Gautama didn't know that, it said hard to go, Tama didn't know about this, and he had been sheltered. So, this was quite a shock to him, went back to the palace, pondered it, forgot about it for a while, the, with them became dissatisfied again, went out with the chariot here one more time, and by the side of the road, there was a, a satu, a holy man, a renunciate, who was sitting and meditating, and the Buddha, I said, hard to go, Tama, I said, here, here, what's going on, what's that man doing? And he says, well, he's living a life that he hopes will transcend death and transcend suffering, and the Buddha was shocked that there was actually a way out of all of that, so he went back to the palace, and decided, he became quite dissatisfied with everything, all of his material goods, all the, the sensory delights that he grew up with, that he was surrounded with, the great food, the music, the women became kind of meaningless to him, because he knew that they were all evaporate, they were just not going to be there someday, he wasn't going to be there someday. That's what the AIDS epidemic was like. So, yeah, so I identified with that so much. So, of course, the rest of the story is, he sneaked out of the palace one night, and without anyone seeing him, he saw it. The women and the palace who were so beautiful, he saw them lying in awkward positions and snoring and looking not so good, and the thing that he was hardest around to leave behind was his wife and son, but he knew that he was doing it for them, and so that he could help them escape suffering, and of death, and birth, and old age, and sickness. And for these, the women who no longer look pretty to him, and for everybody else, we call it the altruistic wish to attain enlightenment in order to free all sentient beings from the suffering slips of sorrow, the Bodhisattva motivation. So, he went on, he studied with a couple of teachers for several years, and became a renunciate, and for quite a few, I think 12 years or so, the surrogacy lived on nothing but bird droppings and rainwater in a cave that you can see down by Bodgaya. The story goes, and eventually, he attained enlightenment, and gave his teachings to the world. And the first teaching was, I think, is a core of what Buddha Dharma is about. He gave it at a place called Sarnhat, which is near Varanasi on the Ganges in India, at the request of some of his, the gods, and some of his fellow monks, and so on, fellow renunciates. And it's what we call the Four Noble Truths, or the Aria Truths. And the first one is that existence is Dukkha, which is usually translated as suffering. Although people who know more about Sanskrit than me say, that vexation is a better term, a more accurate term, but most people say suffering when they talk about this. And there are several different kinds of it. There is a suffering of not having what we want and wanting it so badly. There is a suffering of not wanting what is visited on us and that we can't get rid of. There are a few other divisions of suffering, but the point is, in this is that unlike, say, the Abrahamic religions, Christianity, Judaism, and Islam, we don't suffer because we are being punished, because God is mad at us, but because of our own actions, because it is the nature of some sorrow to live in suffering, that's just the way things are. It's a given, like a law of nature. And the second Noble Truth is that suffering is caused by attachment and aversion. That is basically, as I said, having things that we don't want, that we hate, that threaten us, or make us afraid, or attachment, things that we want and don't have, things that we have and don't want to lose, that we identify with. We want them so badly. And these two things, in turn, arise out of what we call ignorance, which is kind of a term of art. It's a mistaken view of the way things are, which is that we're the most important thing in the world, and whatever affects us in a good way is a good thing. And if it enhances us, we love it. If it doesn't, we hate it. So that's how we judge good and bad. That's how our morality is for most people. And some people characterize it, call it self-clinging, and various other things. We call it my rig fight into a button. I think it sounds good. So that's it. That's our greatest obstacle. Looking at everything through our lens and how it affects us. And the third Noble Truth is that there is a way out of this, and that is we can overcome suffering by overcoming attachment and aversion. And we can overcome attachment and aversion by developing wisdom, this kind of wisdom. We call it wisdom realizing emptiness, which is the Buddhist view that has a couple of aspects that I'm sure all of you watching this already know this, but I'm going to tell you anyhow, that is interdependence is one, our co-depends, interdependent resonation is one, that is, we all phenomena are dependent on others too, and as it arises abides and dissolves, and nothing exists inherently and independently, or eternally, or out of its own volition. Since some things are easy to see, like the water came from the ground, somebody had to make the plastic, somebody had to carry it to me, and because I'm thirsty, I love the water, and I want to take more of it, and to satisfy my thirst. And it tastes so good, my mouth is dry from talking. So I want the water to stay here. There's only this much left, and I'm kind of concerned. So I want to cling to it, I want to keep it with me. But I'm drinking it, so it won't abide forever, and it will dissolve into my mouth, and body, and so on, and go away. So we love it when it's arising and abiding. We hate it when it's fading away. So I'm judging this by how it quenches my thirst, because I'm not a very good Buddhist at all. So the fourth Noble Truth is the path that we do it, and there's several ways of looking at it, originally it was the eightfold path. The right ways of doing various things, and if I was to around it a bit, we divided it down into three different things. A couple of three different things, but as morality is one, not causing harm to others, and developing some kind of understanding, some kind of cognitive understanding of the Dharma, and then putting that, getting that deeper into our hearts and souls are meditating. Another way is hearing contemplating and meditating, another way of looking at it, that is first we come to some kind of cognitive understanding. We call it hearing because in the old days before there was a lot of literacy, that's how words and words and teachings were transmitted, and then contemplating it, that is applying it to what we have heard to our own lives and our own mind, and how we live our lives, and then taking it to another level, meditating and making it a deep thing. So there's another kind of tripartite division to this, I'm sure you all know this, but I'm telling you that anyhow, and that is that we, in Vajrayana, correlate to Hinayana, Mahayana, and Vajrayana, which some people get out track and think that these are the chronological way things happen, but that's not really accurate. It's sort of the way that Tibetans developed this tripartite system over the years. And the first word called Hinayana, or self-liberation, is when we work on ourselves and our motivation is to, in suffering for ourselves, the lowest of the low motivations, they say, is not to suffer right now, and it goes on up to not to suffer in the future, and not to suffer in future lifetimes, and the midling motivations are not to be reborn, but to pass into some kind of liberation. And the highest motivation is, as I mentioned, the altruistic wish to attain enlightenment in order to free all sentient beings from the sufferings of some sorrow. And that's something that we strive for. It takes a long time to develop it as a motivation, especially when there are adverse circumstances that can make you lose it. But nonetheless, it becomes easier to do when we have our foundation of, well, renunciation that is living a little bit separate from the world, if you're a monk, or living in the world, but not quite so identifying with it, not being overwhelmed with these afflictive emotions that we all have. So that's Mr. Dharman, or nutshell. You became a monk yourself, didn't you? Yes, there was, 23, 25, about 25 years in America and here in Nepal and in India. Could you say something about the deepening of your relationship with Buddhism, to Dharman, and you're a lawyer in Atlanta? What are the next steps in terms of your own path? Well, you're starting to practice with a Shambhala, such as such. Something with the Galupus. Actually, being a lawyer in some ways was quite helpful since the law, well, the law is about compassion and so on and so forth and about public policy. But the root of it is logic that a lot of people don't seem to know or appreciate and you just have to apply that quite thoroughly to whatever it is you're doing. And that's a very important part of the Buddhist Pedagogical System debate, although it's a very different debate from what we do in the West. It's not the free-wheeling open debate that we do there. But logic is important as a way to ground your thoughts, your beliefs, and give more substance to them. How did it go? Step by step, my teacher at the time, the Galupus Lama, who was in Atlanta, I've been practicing for a while. He suggested that I take Getzul vows, that is, they're two kinds of months now. Getzul, which is sometimes called novice, which isn't really quite accurate. And Galon vows, and he suggested I take those and they're ten different vows that are divided up into 37 sections. I thought he was joking, of course, but he was serious. He repeated it a few times, so I did. And I went on to visit, I got involved with another lineage. I just happened to be a stumble across them and the teacher resonated with me. And so I became an ordain of that lineage and wound up, I visited India several times from up or so each time, and finally wound up, was in a place where I was able to live there. And I did. Well, first here, for a couple of years, you can't men do, and then in India for six years, in a monastery. And it was a very interesting experience. I'd never been in the military, I'd never been in an all-male environment. And of course, well, a monastery is rather different from that, but it's hierarchical, like the military is. And one of the main differences, of course, is that for a monastery, it's like a kindness factory. That's their job. And to develop that and to spread it, the Tibetans in the old days, and some, I get, many still do, believe that the monasteries are there, they bless the entire region. And so it's important to support them. And since, I guess you could say the vibes, they send out, affect everybody. I think it sort of likes the space program. That is, if you ask most people, most Americans, why do we want to send people into space? What good does it do for us? And they'll say something like, "Oh, well, you know, science and so on." But nonetheless, it's a basic belief that we have, and that we all hold deeply and collectively. And so we have these people who are specialized in doing that, astronauts, and the support systems that they have, and so on. And that's what monasticism is like a lot traditionally, and in traditional cultures. So the monks are, well, in Buddhism, we have three jewels that we take refuge in. The Buddha, the Dharma, the teachings, and the Sangha. The Buddha is all the Buddhas, all the Buddhas, all the fully-enlight beings. And the Dharma is the Dharma, of course, the teachings. And the Sangha is what we call the assembly of in-light beings, our hearts and bodhisattvas. And the Buddha is represented by statues and paintings, and the Dharma by Dharma books, and the Sangha by the monks and nuns, the assembly. And so these three things, or these three representations, are venerated and revered, not for their own sake, but because they generate the person who's venerating them, generates good karma for himself. And so like a statue, like a book, we, the monks and nuns, are just objects of veneration. Mostly, these are the lay folk, that's the biggest job here in Asia. Most of us don't teach, we do other things in the monastery, keeping it together. But it can be an extraordinarily humbling opinion, a humbling experience, very good. So when people are depending on you for that, looking at you for that, you become that, or you strive for that, you try not to disappoint, you try to be worthy of it. That was such a great motivator of the path, of the monastic path. Did you face any challenges in adjusting from your life as a lawyer and, you know, to be very gradual, there were challenges, like wearing robes in America, was more fun than a challenge, I think. I thought about writing a book, lay people say the darnedest things. It was, you know, cute little things like standing on the street corner once, in Washington, D.C. waiting for the light to change, I looked at my watch, and the woman next to me, a complete stranger, said, most hearts are supposed to be concerned about time, and disappointed again. Or, I was walking down the street in Atlanta one afternoon, and a transvest, a drag queen, or a transgender was walking towards me, and wearing, I was wearing my robes as a shagie. As she just stopped, and her tracks looked me up and down and said, "You go, girl." I found out later the appropriate response would have been, "You go too." So things like that were happening constantly. Most of them were quite positive. I can remember, I could probably count the negative experiences I had as a month, presenting as a month, and on one hand. Yeah, people were nice, very nice. And further, unlike some people in America think, people in the rural south and small towns were much nicer and much more polite and much kinder, generally, as a rule, with people in the big cities in the north and elsewhere. I mean, some people were surprised because they think, you know, urban dwellers are much more cosmopolitan, urban, and so on. And that southern is in the country or bridges rednecks, but it's not that way at all, in my experience. So, coming here, well, as I said, I'd been here several times, I think five or six times, before I started living in the monastery. So, I had an idea of what I was getting into. Nonetheless, there were still quite a few things, mostly customs and things that everybody knew, but I didn't. And there were nuances that I was missing constantly. And unlike a lot of places, there's no training. There's no training film. There's no orientation. You're thrown in, you pick it up. You have to ask people what to do, how to do it, what's going on, a lot. That's, I think, as far as one of the shortcomings in monasticism, and here in Asia, that is where, well, most people who grow up here, they kind of know what's going, they know what to expect, because they grow up in this culture where monasticism is so prominent. In America, we don't. And that's one of the things that could be improved upon there, that is, when people go into it, the monastic life, it would be nice if they know what's happening. Since there are so many false assumptions that people have about it, like, you know, very few others have come through, for example. And even fewer can levitate. That's just how things are. Curious, you were talking about, when AIDS came, and the terrible loss of your inner circle and many others. Also, the Cassandra dimension of the entire thing. I'm actually curious, I have two questions, really. The first question is, how is it you think that you were able to cotton on to what was going on, Cassandra-like, how are you able, how do you think it was that you were able to cotton on to realize, to realize what that it was going to be, as you said, not just horrible but awful when others didn't. I'm curious, that's one question. And the second question is, and then, of course, you yourself were diagnosed, going into the monastic situation. Did you have to deal with that stuff, that psychological and emotional material? Can you hear me? Yeah, I hear, but I don't quite understand. Well, some people might call that trauma. Well, let's deal with the first one, which was, how did I know what was going on? Yeah, when so many others didn't. Well, I was, like I said, I was editor of a gay newspaper weekly, give away, and as HIV AIDS emerged as an issue, I was getting more of that information than most people, than probably anybody in town. Those of us who worked in the paper, and it was bad news. We subscribed to the CDC's weekly morbidity and mortality report. And it was so apparent that the funds, it wasn't being funded as much as it should be. By the time that toxic chucks syndrome and lesion, heiress disease and another disease, there was prevalent back then or emerging back then, it killed that many people. Total AIDS had killed more than all three of those combined. And it was apparent that something had to be done and that nothing was going to be done. A lot of it, of course, was homophobia. There were what we call the 4-H club, homosexuals, hemophiliacs, heroin or IV drug users and Haitians were the ones that were most well known, most associated with it at the time. And aside from hemophiliacs, we weren't the most popular folk, the marginalized people in society. And fortunately gay folk came in, we were used to being marginalized and further, we were a community in those days. We were a self-defined community. We have since due to assimilation and progress, become a niche market. And a little more than that, I think. But in those days, we had to look to each other and depend on each other for everything. We, for the regay doctors, gay dentists, gay merchants, many openly gay people rarely worked for corporations since there was only so far they could go, even if they were hard. So there were a lot of small businesses owned by gay folk. And we, of course, they depended on everybody, everyone's good will. And there was that sense of community that was happening. And also, we had just come out of several years of activism and political action. And so we kind of had a clue of what needed to happen, and how to make that happen. So, but later on time of that, as I mentioned, was this constant death and dying. All of one's friends, like, it's an arm-a-way to die. And in those days, as you all may know, there were no meds until, I think, '88 or '89. And they weren't widely available from '90. And there was a very, a med with a lot of side effects called ACT. So there's nothing that could be done, nothing, nothing. It made you feel incredibly helpless that not only were you probably going to die, and there was nothing that could be done, because you couldn't do anything for anybody. But I had to find something, maybe it was because I'd been an attorney that just listening to people and letting them talk, and letting without telling them what they should think, what they should feel. Being non-judgmented, and it felt like attorneys usually are, other than, you know, advising the client as to what the law is. That was very helpful. It was probably the greatest thing that I could do for my friends, is just to listen and let them process what they had to go through. I found out later it was called active listening. But yeah, that's something I learned back then. What I learned about death and dying was that a rather about grief, that there was a rhythm to it that I could see because so many people were dying. So I could, as I mentioned earlier, I could see emotionally what they were going through. I could see in myself what I was going through. And when people died, the grief sometimes was overwhelming. Sometimes it wasn't. Sometimes it was just, it was interesting. I could go to funerals, and I could tell who had an HIV or an agent who did, because usually they'd be, often they'd be relatives and friends who were just yelling and screaming and being very upset and crying a lot. And of course, you know, their loved one had died. But then there would be others who just had a thousand yards stare because we'd seen it before. We'd see it again. It became, but now. So they say in the West that it's very important to getting touch with our feelings and express them and to process them in order to transcend them. Advertism to the contrary. When someone dies, we're advised not to hold on and cling to them the person, because it prevents their consciousness from moving on to where they have to go. It holds them back. And we're advised not to show, not to cry, not to wail and moan and grieve around them, around the corpse at first and so on. So these two conflicting things, what do you do? And what I found out the thing to do, the way I came to think about it was that I had to put it. I had to do it, but at the same time I had to not do it. And I would, I would grieve, but not so deeply or not so overwhelmingly, as I had prayed previously. And it's, it's kind of grew a bit. And I kind of recognized it sometimes grief of a loved one. Sometimes it's overwhelming like a huge flood. And sometimes it just kind of, it's like a slow drip that is on you. Sometimes it's sort of like a mist, a fog, the colors it's everything you see and proceed. But it's so very subtle that you have to really look to be aware of it. And when you do, you see it. So I learned how to experience, not experience. Later on, I heard a story about the Dolly, the Richard Giro's tell about meeting the Dolly Lama. And the Dolly Lama was very interested in actors and acting, especially film actors because when you act, especially in film, you have to actually call up these emotions, emotions, and express them. And you actually have to feel them and manifest them in your, your face and your eyes, as well as your voice, body and so on. And he was very interested in that and how you go about doing that. That is you. It became similar to that. That is to say, I knew I had to go through it, but I also was watching it. Another metaphor that was quite apt was that of a magician who in old, olden times here would entertain a crossroad. So I used to do it down here in, in, can't do it, the big park, that's now before they close it. That is, there would be traveling magicians who would go to crossroads or a small village. And one of his tricks would be to throw out its powder that caused people to hallucinate and to see beautiful celestial mansions and gods and so on. And people would be over-odd. And the magician himself would see this too. But the difference was he knew that he was, what was going on. He had an understanding of it. And due to this near constant death and dying and sickness for these, those 15 years or so, like I say, it became but now I got to know it well. Death became my friend. Dying became my friend. I got to know them intimately. And they're not friendships. I would advise contemplating. But there's something about that kind of familiarity that gives you a handle on it. And you were quite convinced that you would die relatively soon. Yeah, sure. Of course. Like everybody else it was. But I did what are major's old tricks. What do you make of that? What do I make of that? Call me Ishmael. This stuff won't survive her in roby day. It only seems left to tell the tale at one of the few. What else about that time? Should people know about it? Or is there the same? Good question. I know. Really. One just has to somehow get through it. Or not. As the case would be. So you're a reconciliation with that. Or you're dealing with that, processing that. Was it sounds like through this Buddhist view of grief, emotion, reality, et cetera. There's a practice in which well, there's a one of the Buddhist yiddhoms. Monjushri is the Buddhist side of wisdom. That is what we call it. We call it wisdom realizing emptiness. But it's having a great understanding of the exact nature of things. And how everything is impermanent. Nothing is eternal. Nothing is solid. And so in accepting that learning to live with it. He has like most of the yiddhoms of the Bodhisattvas, there's several manifest stations. And his rasmal manifestation is called Yamantaka in Sanskrit. And he's said to be the most rasmal of all the rasmal deities. And he has implements in all of his arms. And when the other rasmal deities see him, they all drop their implements. They're so afraid of him. And Yamantaka is a Sanskrit for conqueror of the Lord of death, conqueror of Yama. And that got me through a lot. Can you say more about that? Well, I don't know that we actually conquer death, but we can conquer our fear of death. We can conquer our anger, we can conquer our depression and everything else. We have to go through when we're in a situation like that. If we have a deep and strong enough understanding of how things are. And what was the second one that you asked? Well, we're edging into it now, actually. I was asking how it was that you dealt with all of that as some people would describe it these days, trauma, trauma, which has several layers to it. The death of all those people close to you and others, your own Cassandra dynamic in the whole post on the whole thing, just terrible. And also your own diagnosis. Yeah. Well, it turned out to be not so. Well, when I were very well being diagnosed or getting the test results, I went back to my office and cut my finger on a staple and a little piece of dropping blood came out and I thought, this could kill people. They didn't. I hope I didn't kill anyone. But I've been sick from HIV phrase only one time. And it was a lymphoma in '99. And I saw oncologists in Atlanta. This is doctors. This is how you do not do bedside manner. The very first consult I had with him, he concluded with, you're in good health. You should live three or four years. I was able to get into a program at National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute in Bethesda, Maryland, an experimental program that for people was my kind of lymphoma, HIV related lymphoma, AIDS related lymphoma. And I lived more than four years, which was quite surprising. I thought I was going to die. Had a recurrence of it. It was very, this was '99 after the meds came out and I'd been on them for a while. And it was interesting in that when I was diagnosed and thought I was going to die, it's all like home. I've been so used to it for so many years. And that's kind of what happens, well, they say, according to the Elizabeth Kubler-Orschima, that when you go through all of this anger and depression and bargaining in denial, you come to eventually acceptance. I don't know how much I did. Sometimes it comes and goes. But compared to, at the time, my parents were quite old and compared to how they were handling their imminent demise and my friends were handling it, I think we were doing a better job of it. That is, we saw it all around us, as I said, it was but now it was commonplace. They're awful things, but fear is not one of them. They're worse things in fear. It's horrible. So that's that. And as I said, I have, and this is one AIDS-defining illness. And when you have one of them, you are said to have AIDS for life. That is, you don't go back to just nearly HIV or so, whatever. It's semantic, but there's a long story about how that evolved, it had to do with epidemiology. So in the '80s, how they were reckoning what AIDS was and what it wasn't. But nonetheless, I have it, I'll always have it, even though I'm healthy and my meds are great and so on. But it's like, after you have lymphoma or after you, after you, the actual tumors are more or less, they're not to cancer themselves, they're some kind of tissue that the body produces. And even though I was, had no more cancer that I knew of, at the main site, I would still feel this phantom pain for months, years afterwards. And it was like Mr. Death was saying, "You got to wait this time, but I'm going to get you sooner or later." And he will, but not today, not tonight. Should we take a break? Sure. I was in transition with the monastery. I was going to go from one to another. I'd been living in a shed and teaching English and other things. I was going to go to another facility. But before I did, I went to America. And the COVID epidemic came. So I was trapped in America for quite some time. And living outside the monastery, I've become so accustomed to it that it didn't seem to make sense to be a monk without a monastery. Along with quite a few other things. That is the transition I was going through. And I was around a lot of old friends who were living their late lives. And some of them had been political friends, allies and whatnot. So that was that. There were so many things available online, teachings and practices from all over the world any time of the day or night. So I kind of turned into a retreat, solitary retreat, since we couldn't -- it was not advisable to leave the house at the time. So it was more like just being a renunciate, a hermit. I could have been in a cave in the remote Himalayas rather than a staying in a room in the wrong side of the land. So that kind of -- it was more challenging, too, in some ways, that it's not going to have the support of all of those the other monks around. But on the other hand, I really did enjoy the freedom of less regimentation. As I said, I'd never been in the military at all. So I'd never experienced that much regimentation, that much authorities. And, you know, I'm a child of 60s. Anti-authoritarianism is us. So it came out. It was a learning experience. I'm glad I did it, just to have a move forward. Do you have aspirations for the next phase of your life? You've been out of the monastery a few years, and you're settled here in Kathmandu. Well, I'd like to, you know, remain a knock to do my practices. And in addition, as far as the lace work stuff goes, I'd like to work with people with HIV, especially nearly diagnosed people. And especially gay men have been nearly diagnosed since there's a great need for it here in South Asia. Gay men with HIV are -- they're kind of in a double closet. That is, very few people are gay men are out here. And homophobia is here, but it's a different kind of homophobia than in the West. It's qualitatively different. So I wouldn't get into that, but nonetheless, nobody wants to come out. And then when they are diagnosed with HIV/AIDS, some not only are not comfortable telling their gay friends, if they haven't, but even their families sometimes, they keep it from them, which is horrible. They're incredibly isolated often. And further since many people here -- or more people here are unfamiliar with HIV/AIDS -- than in the West, many people think it's like it was 40 years ago. And their death is imminent. And they seem to be impressed. People are impressed that I've had it from 39 years now. I've never diagnosed 39 years. That gives them hope just by being there. So I think I have something to offer. I have a couple of HIV/AIDS related online groups that people come across, mostly Indians. Of course, Pakistani, South Asians, people from around the world. That's the focus of it. And I'd like to help them get through it, because when we're diagnosed with AIDS, especially when you're relatively young, like most sexually active, people are who are diagnosed, we do die. We have this notion, we all do, when we're young, that we're going to live forever. And that's just the way we are. We're full of life. We can't. And especially in America, where we're not around old folks who die a lot. We just think, oh, yeah, we're like that. 30 is so old. I'll be dead before I'm 30. A lot of people say, well, you won't, probably. But nonetheless, there is something that dies when you're diagnosed with HIV or any disease that you think will kill you. And what dies is the way you think of yourself. You think of yourself as young, as healthy, as the world is, you're oyster, as you can do anything. And then suddenly you realize, someday, and someday soon, you're going to be nothing. And that takes some getting used to. You have to let that person die and you have to give birth to another, or transform into another. And I like helping people in that transition. It's very, very meaningful, because, of course, I feel like I'm helping myself, and healing the own wounds. What have you learned about helping people with that transition? Mostly soliciting, just soliciting. And, you know, I give information about practical things, like what drugs might be better, what drugs might be worse, health care and management. And there's a lot to know. It's a systemic disease. And there are all kinds of things that you really need to know to take care of yourself. And you have to. That's one of the things that happens over the years. If you don't take care of yourself, you don't do so well. So there's that. But mostly it's just soliciting, as I said, active listening. I think that whistle means it's time to go. I've time here as imperatives. It's no more. Most HIV meds are made by a company called Gilead. And one of the ones that they were making some time ago was called Tenoff of your DF. Now there's a different formulation that's safer. But in those days, we didn't know that it caused osteopenia, osteoporosis. And I slipped on some water. Very simple slip and fall. And broke my femur, my right femur, very badly. So much so that this leg is now four centimeter shorter than the other one. And will be forever. So I call this my Gilead limp. And it's probably, I mean, it's the worst result of having HIV aids. And it's kind of an indirect effect. But I'd rather be limping than dead. Sun and the 10 shows you're funny, tell me they paid it. I'm going to take it. I got not you don't complain. See, basically, the way to watch it. What I say in 30 years will be his desert. Do you think so? It can't be a new valley. Do you reckon so? I don't know. I'm not so good at predicting the future. Would you like to know another interesting story? These, oh no, where are they? These. Have you seen these before? Yes, I have. You don't know where they come from, where they originated? And they end these. And so it was part of the hippie trail that as people would go down there to take, what is the word? It's become popular in a way. I waska. Yes, that's it. And other things. And so people would, you know, buy these to take home and wear them. It'd be cool. So everybody would know how cool they were. So in addition to being cool there, they would come here and be cool. And so the people who live here to go to Benton's guru and tomorrow they started wearing it as well. Where psychedelics are a big part of your 60s experience in '68 when you went to San Francisco. Well, I tried everything at least once because as a friend of mine said, you might not get it right the first two or three times. But yeah, I was never really, it didn't attract very much. Acid was sort of, what was it? It just kind of made me, what is the word? Nervous, paranoid, generally. Yeah. The only one I really liked was opium because it was so subtle and relaxing and you could let your mind flow. But fortunately it's very rarely found in the West. So that's what saved me from a life of drug addiction, I suppose. Yeah. No, no, I wasn't much of a drugging. I was kind of a failure as a hippie. Well, you became a lawyer, I suppose. Yeah, might as well. So I defended people who were drugies a lot. The law firm that I worked with, the Legal Collective, was my first law job. It was, like I said, there were people who were really unsung heroes. A lot of them did the litigation that implemented the Great Society and Voting Rights Act and the Civil Rights Act of '63, I think it was. And they did so much and they gave so much and many of them are at least the ones I worked with. I also made a career out of representing drug dealers who, big-time drug dealers, who had a lot of money and could afford it. And so basically, that paid for the Civil Rights litigation that we did that was not remunerative at all. So you were telling me before that you often come to the stupel, miss every day. Yeah. What's your regime then when you come here? Just walk around and say mantras. What kind of mantras do you say? I mean, you, in particular. The, oh, I say, I keep forgetting I don't have to look at you. Yeah. Well, I say the mantras of my main practice. And also, al-mani-pehmi-hun, the mantra, chin-raisig, or avela-kita-svara, who is the most practiced Yidam, or in Vajrayana, in Tibet, in Tibet Buddhism. He's said to be the Bodhisattva of compassion, who is a manifestation of all the compassion of all the Buddhas and Bodhisattvas. But he's also, the thing about that is, well, compassion we define is the wish that all beings be free from suffering and the causes of suffering. And conjoined with that is what we call wisdom realizing emptiness. So, the idea, the goal of practice could be summed up as the union of those two things and realizing them deeply. That is, knowing that, hmm, they're subject and object, like, I feel compassion for you, but try to. And, which is important. However, at the same time, that compassion is dependent, dependently arisen. Since, if I weren't here, I wouldn't be feeling compassion for you. If you weren't here, either in the flesh or in our brain, it wouldn't be existing. It would be empty. It would not happen. And the act of it is the third leg of this tripartite system that makes it happen. So, we have to, ideally, realize those at the same time. And it takes a while, a few lifetimes, to get it down. So, we have to, we have to, we have to, we have to, we have to, we have to, we have to, we have to, we have to, we have to, we have to, we have to, we have to, we have to, we have to, we have to, we have to, we have to, we have to, we have to, we have to I was at a retreat once in the mountains in North Georgia. And we were meditating on, we're developing, learning what we call the four majorables. And one of them is to generate compassion. Well, for those who have helped you, those who are neutral and those who have harmed you, and it helps to actually bring to mind someone in your life who has done this, who fits these categories and develop compassion, love and kindness, equanimity for them. So the one I fixed on was this fellow who I've been doing politics with. He was a gay man. And we didn't get along at all to say the least. He was rather conservative and he really didn't understand the way advocacy works. He kind of had this idea that if you were respectable enough, everything would fall into place. And it doesn't. There's a lot of work and a lot of thinking that goes on. And I was more of a free spirit still am. So I would, and he would do things that were really quite horrible. I guess it's a word that would frustrate me. And some of them were rather personal. So I took him as the object of someone who has harmed me. And so I would try to generate compassion for him. And we have all of these ways to do that, thinking, such as thinking of someone who, thinking of everybody, is having been our mother at some time in our countless millions of lives, and the billions of universes that we've been through, and who took care of us, and nurtured us, and carried us in our stomach, and did all kinds of horrible things to protect us because she loved us so much. And when people who were harming us, we'd think of them as having, because of their past trauma, they now have these afflictive emotions. It's clouding their vision. And that is what's causing them to act out in these ways and express these harmful afflictive emotions that they've heard us. And so we try to develop some kind of feeling. Posh, I'm being interviewed. We try to develop some kind of feeling, even for barking dogs, who are getting in the way of my exposition. So he was the one I chose, and sometimes I could go for as long as 15 minutes without getting pissed off all over again about what he did. And so the retreat was for a weekend. I went home. Monday morning I was eating breakfast, reading the newspaper. We had newspapers back then. And there was his obituary. He was not even in existence in this life as we know it. He was right here. It was something I was carrying around in my head. So the way I was feeling about him was like, you know, if he was alive, I'd be upset with him. But he wasn't. Nonetheless, he was, this is my new friend, I suppose. So that's about all I have to say. Good luck folks. Thank you very much. Thank you for listening to another Guru Viking podcast. For more interviews like these, as well as articles, videos and guided meditations, visit www.guruviking.com.

In this episode, filmed on location in Boudhanath, Kathmandu, I am joined by Dorje, an American Vajrayana practitioner born in 1947.

Dorje recounts his childhood in the American South, his move to San Francisco in 1968, and his involvement in the early days of the gay liberation movement. He recalls the arrival of AIDS in 1981, the traumatic deaths of his close friends, and the impact of his own HIV diagnosis.

Dorje explains his conversion to Buddhism in the midst of a chaotic and stressful life, his 25 years as an ordained monk, the power of Yamantaka practice, and his understanding of the spiritual path.

Dorje also explores the deep relevance of the core teachings of Buddhism to his experience of the AIDS crisis, describes the rhythms of grief and death, and shares what he has learned about helping the dying.

…

Video version: https://www.guruviking.com/podcast/ep262-life-of-liberation-dorje

Also available on Youtube, iTunes, & Spotify – search ‘Guru Viking Podcast’.

…

Topics include:

00:00 - Intro

01:03 - Dorje’s upbringing

02:07 - Dorje as a boy

02:59 - Career aspirations and becoming a lawyer

04:16 - Arriving in San Francisco in 1968

04:38 - Involvement in the civil rights movement

06:28 Early days of the gay liberation movement

09:13 - The Cockettes

11:48 - Gay political organising in Atlanta

14:02 - Arrival of AIDS in 1981

15:21 - Deaths of Dorje’s close friends

16:10 - Dorje’s HIV diagnosis

16:45 - Stages of grief

18:50 - Dorje’s HIV related legal and political work

20:39 - Activism vs realpolitik

23:06 - Encountering Buddhism

25:08 - Reading DT Suzuki and Evans-Wentz

25:46 - Shamata in a highly stressful of life

28:29 - Drawn to Tibetan Buddhism

30:39 - The life of the Buddha

33:57 - Modern insulation from sickness and death

36:14 - The Buddha’s quest for enlightenment

39:18 - 4 noble truths and the core of Buddhism

42:26 - How to develop wisdom

44:10 - The spiritual path

47:38 - Ordaining as a Buddhist monk

52:12 - The 3 jewels of refuge

54:05 - Challenges of living as a monk

56:14 - Moving to Nepal

57:48 - Why were some people slow to recognise the danger of HIV

01:02:25 - Helping the dying

01:03:27 - The rhythm of grief

01:06:43 - Actors and magicians

01:08:42 - Facing his own death

01:10:01 - The power of Yamantaka practice

01:12:10 - Living with an HIV diagnosis

01:17:06 - Leaving monasticism and solo retreat during Covid

01:19:28 - Aspiration to help those newly diagnosed with HIV

01:23:19 - How to help those with a new diagnosis

01:24:10 - Side effects of medication

01:25:31 - Climate change in Kathmandu

01:25:42 - Hippy trail and changing fashions

01:26:35 - Experimentation with psychedelics

01:27:51 - Unsung heroes of civil rights

01:28:53 - Dorje’s Great Stupa kora practice

01:30:07 - Compassion and the goal of practice

01:31:33 - Kora around the Great Stupa

01:32:34 - Developing compassion for others

…

Boudhanath Interviews playlist:

- https://youtube.com/playlist?list=PLlkzlKFgdknwvU82dU487LhF_mF4AkGek&si=gFGJpi-fnLtxeyZ5

…

For more interviews, videos, and more visit:

- www.guruviking.com

Music ‘Deva Dasi’ by Steve James