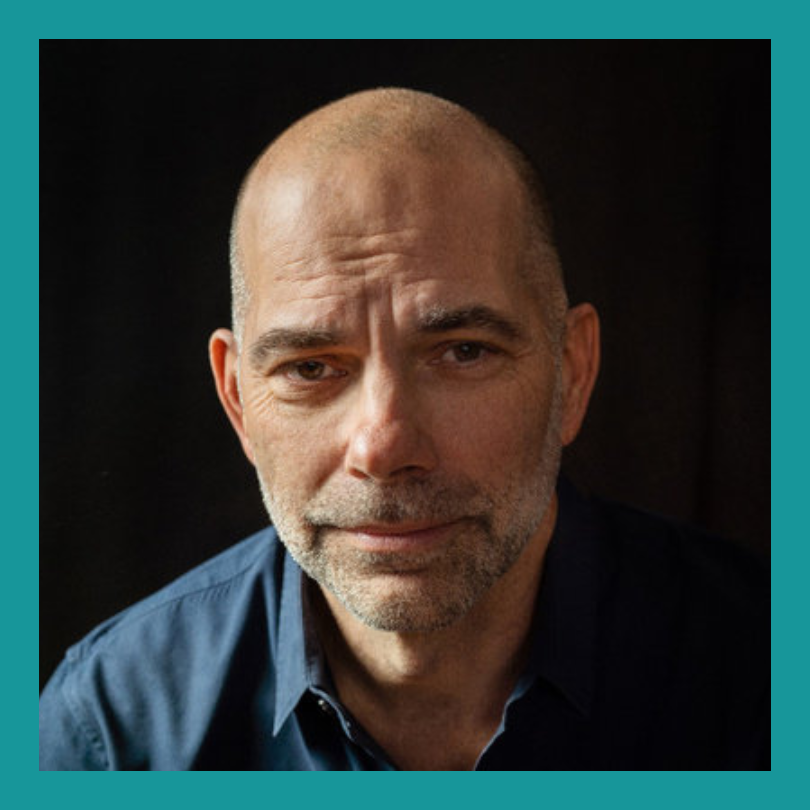

When we think about the good things in our life, our career, the relationships we have and our lifestyle, we often frame our success in terms of what we put into those relationships or how hard we've worked. We attribute the fact that we've earned the successful life that we have today through our personal commitment, the diligence we do, goal-setting, the important choices that we made, and of course, our incredible effort. Those are the things that really made us who we are today. At least that's what the voices in our heads are telling us, for the most part, right, Kurt? I mean, the problem is this, those voices inside your head that are telling you that everything that you've done to be successful is because of your hard work, those voices are lying to you. At least that they're not telling you the whole truth. I would say the way I would say it is that hard work makes success possible, but not always probable. And so, yeah, it's definitely an important factor to work hard at what you want to do and believe in, but there are just some things that get in the road of success that are beyond our control. In other words, life's ups and downs aren't as simple as just saying that my success came from hard work and my failure came from bad luck. Yeah, life is much more nuanced than that. There's tons of research to support that conclusion also. In today's episode, we're going to hear from researcher, author, and podcaster who has explored this interesting voice in our heads for most of his career, and he's going to help answer this question, where does our success come from? Welcome to Behavioral Groups, the podcast that explores our human condition. I'm Kurt Nelson. And I'm Tim Hulahan. That voice you heard a moment ago was that of our guest, Bob McKinnon. We were introduced to Bob and his amazing podcast, "Attribution", by a past behavioral groups guest, Jeff Wetzler. And by the way, if you're interested in hearing about Jeff and his wonderful book called "Ask", you can check out episode 412 from April of 2024. Bob's work as a researcher has focused on attribution, that part of the human condition that assigns cause or blame to things that we and other people do. Attribution happens all the time. For example, when we hear someone say something with an angry tone in their voice, we instantly infer that they were angry at whatever was being discussed, or the person that they were having the heated discussion with. That's attribution. And while we may not be wrong, we also may not be right. It happens all of the time. Attribution is a set of shorthand heuristics that help reduce cognitive load. And reducing cognitive load makes it easier for us to handle more difficult decisions throughout the day. So as with many things psychological, it's not that attribution is bad or good, it just is. But attribution can get in our way as well. Yeah, it can, Kurt. You know, the fundamental attribution error is one of the most egregious of all of our biases. And it's the thing that we're talking about earlier. The fundamental attribution error is running at full throttle when we blame other people for not succeeding because of their lack of effort or smarts. But we tend to believe our own failures are a result of some kind of terrible circumstances or bad luck. Another way to look at the fundamental attribution bear is that we tend to attribute other's behaviors to their personality or character or effort while overlooking the external factors that could be influencing their behavior. This can lead us to make snap decisions in inaccurate assumptions about those other people. And attribution goes beyond just how we think about ourselves and think about others. It could actually have an impact on how people actually behave. And so imagine you're a kid and you don't feel welcomed in a classroom. And so now you sit in the back of the class. And we know through studies that people in the back of the class get called on less. And people get called on less often don't do as well in school. And then you don't do well in school and what happens. And so I think that there are these ways in which we can embrace others instead of judge them. We can be vulnerable for else. We can try to learn other people's stories and tell our own stories in different ways. Yeah, attribution is a big deal. And our guest Bob McKinnon is an expert in it. Bob is also a children's book author and a podcaster. And we recommend checking out his podcast. It's called attribution that is spelled with an at symbol at the beginning of attribution. So at symbol T-R-B-U-T-I-O-N. It's cool. Yeah, it's cool. And he has a great number of fantastic guests. And they talk about all areas of life that get impacted by how we attribute different things. In our discussion with Bob, we talked about the concept of attribution and how it affects perceptions of success and failure. The role of luck and environmental factors in success. Especially when compared to the belief that hard work is the main driver of everyone's success. We also cover the importance of telling more nuanced stories to promote understanding and empathy and how using compassionate curiosity can be abridged to political and social divides. Which reminds me that we need to show some gratitude. Once again, to our previous guests, Kwame Christian in episode 251, who introduced us to this amazing concept of compassionate curiosity, of which I hope we don't have to pay a royalty to. Oh, I hope not either. Because we would be more broke than we already are to. There you go. With that, Grovers, we hope that you sit back with a clean, poor, accurate attribution and enjoy our conversation with Bob McKinnon. Bob McKinnon, welcome to Behavioral Grooves. Thank you so much for having me. It is our pleasure, and we'd like to find out first, would you prefer to have dinner with your favorite musician or your favorite actor? Oh, I was going to say musician, but then I was trying to see if I could gain the question and figure out someone who was both. Oh. Oh. Yeah. So I think, did I say musician? I think I might say actor. Yeah, sorry actor. Yeah. Would Johnny Depp count as both? No. In fairness, I hadn't listened to much of his music. Yeah. Who would the actor or actress be if you had your choice? Yeah, I think there's a couple. I mean, I've always respected the work of Ethan Hawke, who is also, you know, and so that would be a good choice to talk to, you know, he's no longer with us, but I would have loved the opportunity to talk to Robin Williams and have that conversation. But, yeah, so that's probably where I would start. You know, we didn't mean to start off with a stump the guest kind of question here, but that's okay. You know, maybe the second one, it will be a little bit easier. Yeah. Well, you know, it's funny. I listened to some of the previous podcasts, and I will admit you did give some easier questions to the, to the, to the other guests. You're a podcast. Here we go. Yeah. We, you know, we will, we'll maybe make it up here. Okay. Are you refer coffee or tea, which is your preference? Yeah. It's definitely coffee. Although I should say the coffee is simply a vessel for milk and extra sugar. Oh. Oh, nice. Yeah. That's good. I am the coffee is the vehicle for the flavored cream. So it's basically the same thing, you know, but I, I do like that vanilla or the, you know, every once in a while, some, some other kind of yeah, or you, or you, or you, or you just go, go right in on like hazelnut flavored coffee, which is really great. Yeah. There's things for her. Yeah. It's, it's funny though, because I buy the big, you know, cream container and I have it in the refrigerator and I, and I go, it, it disappears much faster than me just using it. And I've realized that my daughter now is like, she doesn't drink coffee, but she puts it in her chai tea. She puts it in like mixes it with milk. She, and so all of a sudden it's like, this should last at least two weeks and it's gone in a week. Yeah. Yeah. That's crazy. All right. Foraging. Okay. Bob, if you were able to live to the age of 90 and retain either the mind of a 30 year old or the body of a third year, 30 year old for the rest of your life, which would you prefer? Well, that's a trick question because my mind is a 30 year old was not particularly well formed yet. So, so I probably was wiser, older, but I think I would generally go with sort of like keeping my mind intact. Yeah. It's a tough question because you have, you know, and as Tim and I have discussed this before, it's like, well, is, is your body, you know, totally sickened and you're in pain the entire time? Are you, you know, so there's all sorts of nuances when you start to, to dissect that back down. Yeah. Yeah, I think it'd be nice to have like a dial where you'd sort of just dial where your body and your mind is, you know, yeah, there you go. Yeah. That, that. Perfect mix. Yeah. It'd be like nighttime guy and daytime guy. Yeah. All right. So last of our not so speedy speed round questions for you, Bob, does our success in this world come strictly from hard work that we put into it and that anyone who puts in that hard work can be successful, which means that anybody who is not successful just isn't working hard enough? Yeah. No. Yeah. I would, the way I would say is that hard work makes success possible, but not always probable. Yeah. And so, yeah, it's a, it's a definitely an important factor to work hard at what you want to do and believe in, but there are just some things that, you know, get in the road of a, of success that, you know, beyond our control. Yeah. And it's one of the things that we want, we'll talk more about this as we get in because I think it's a key, key component of some of the, the work that you're doing. So, so with that, Bob, you are the host of a great podcast called attribution. You're a best-selling author and you've been published widely across the United States and the world. And today we're here to discuss an article, plus maybe some other facets, but you wrote an article in the Greater Good magazine called why do people succeed or fail in life and your answers matter. So let's start with what got you into this topic, this kind of whole, like, what people makes people succeed and fail. Yeah. So it was a, it was a very, it started off as a very personal journey, right? And so, you know, I have by most definitions had a pretty successful life, right? And, but I know people who I grew up with members of my own family who have had different outcomes. And, you know, I went through a lot of my, you know, twenties and thirties feeling pretty guilty about that and thinking like the world wasn't quite fair and questioning sort of why I was achieving certain kinds of, you know, successes and having certain kinds of opportunities where people I loved and cared for did not. And I knew that while I was working hard, I wasn't working any harder than my mom who was a bartender, my brother who, you know, works at Harley-Davidson, my sister who was a, you know, then a nurse and then subsequently a truck driver. I mean, I just knew a lot of people who worked their asses off and, and that that was not the sole reason why we could attribute one person making it or not. And the same time I was doing a lot of work with foundations and nonprofits. And I was seeing that there was this, this barrier, this limiting belief that, you know, for example, if you took a school that wasn't performing quite as well, and you knew that systemically there were some things that you could probably improve within that school, people could always point to like a couple of kids who got out or who did well and say, well, why isn't everyone sort of working as hard as they are? And so I saw it as a limiting belief in our culture. And on one hand, you know, you want people to believe in themselves. You want people to work hard to achieve their dreams. And it is so important to do so and to have that belief that you are in some ways an agent of your own destiny. On the other hand, as a country, we need to sort of be more aware of the kinds of things to get in people's way. And so we can create more opportunities for all. And I think that we haven't necessarily had as nuanced a conversation about that as we should, and it's problematic when we don't. I'd like to go back to this realization. You say that you started noticing these differences between yourself and your mom and your brother and your sister. Was there like a catalyst moment? Was there like one thing that was like, wait a minute, this is something that's really wrong here? Or did it sort of evolve over time? It was an evolution. I mean, when I first graduated from college, it was the only person my family to do so. And I wanted a career that was fun and would potentially, you know, be financially rewarding. So I could, you know, make a good living for myself and do some nice things for my family. And so I was in marketing for a while, and it was fun. And I met some of the best friends I still have to this day. But I would see things and how things were being discussed as it related to like consumers and targets and things like that that were frankly off putting, you know, like for example, like I grew up and I was a heavy kid, you know, and, you know, the height of obesity. I got an opportunity where I was working to do a project for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on helping kids find their verb, right? You know, what can they do to get physically active? And that was really rewarding. But I had a guy who sat next to me who was a friend who was working for a food company and he comes down one day and he says, "Check out this new product we're launching." And I said, "What is it?" And he says, "It's a sausage wrapped in a pancake that you dip in syrup." And I said, "You know what I'm working on, right? Because I was working on this, you know, anti-obesity campaign." And he's like, "Yeah, but it's only meant to be consumed in moderation." Oh! And yet I knew that this was going to be a product that was going to be marketed to certain kinds of kids and that it was going to be cheap like fast food and cheap food often is. And I was like, this is, you know, we've got blind spots. And then similarly, you know, when I was growing up in Boston and we didn't have a whole lot at different stages of my life, we were on government insurance, Medicaid. And when we weren't, you know, the nonprofit provider at that time was Blue Cross, Blue Shield. And I remember there was a RFP, you know, to sort of like, you know, win their business. And if you read the RFP, what you were basically seeing was that there was a concerted effort to get more profitable customers. Yeah. So people who, you know, didn't have the helmet, and I was just like, you know, this doesn't seem right. So there was, so that actually led me to a transition out of the corporate world and doing more work specifically with foundations and nonprofits and using the best practices from the private sector to the greater public good. And it was over that where I was just sort of seeing other ways in which the American dream was being used as an excuse to not help people, you know, because you should just work hard and people should be able to do it on their own. And so to that end, there wasn't necessarily, you know, a huge epiphany in terms of this question, but it was one that was, you know, dogging me for a long time. And one, I just got more and more proximate to. Yeah. So one of the things that you said earlier in talking about the school system and, you know, the school may not be performing, but there's always that one or two kids that kind of, you know, excel and are working really hard and do kind of break that cycle and various different things. And we know a lot of your, like the paper that we were, we referenced up at the front is about attribution. Yeah. And so can you tell a little bit for our listeners about attribution and how attribution kind of describe what it is for those who may not know if most of our listeners probably do, but describe what it is and then talk a little bit about how misattribution can lead to some of the issues that we, you've seen and kind of are talking about. Sure. So I think on its simplest terms, attribution is exactly what it sounds like, how, what do we attribute a certain outcome to? And that could be an individual outcome, like, you know, why a team won a game or it could be something larger, like, you know, how did I end up where I am in my life? And that the way in which we think about attribution affects the way in which we walk around the world and how we see others and how we act towards others. And I'll give you an example. One of my first introductions into attribution was through the work of Paul Pith, who I think is at UC Irvine now, and he had done this study called the Monopoly study, kind of familiar with it. But it's fascinating, and it is essentially where you take two people who going into the study are not sort of like, they're similar in terms of who they are and where they come from. And it begins before they play this, you know, truncated game of Monopoly, they essentially flip a coin. And whoever wins the coin flip starts the game with twice as much money, they get twice as much when they go around go, when it's their turn, they get to roll both die, and they get the Rolls Royce is their sort of piece. And conversely the person, conversely the person who doesn't win, you know, he or she starts with half as much money, only gets half as much when they pass go. They only roll one die, and I think they're the shoe. And as you watch these, as you watch these two players over the course of the game, it's fascinating because all of this was recorded. And Pith had a couple of sort of markers that they were going to measure during the course of the experiment, including the sound on which someone was moving their pieces. And so the person who is the Rolls Royce is literally pounding the table with their pieces, like being more authoritative as they go around. They start talking more sort of condescendingly to their opponent, like, oh, you're in trouble now, or, oh, you know, looks like I'm kicking, you know, but, you know, things like that. And then they even had community pretzels in the middle of the table. And they measured who ate more pretzels. And I think that the Rolls Royce took like almost 20% more pretzels than the other person. And the most fascinating thing about the experiment was when the game was over, and the Rolls Royce invariably won. How could they not, right? How could they not? Why is this much money twice the dice, yeah? They were then asked why they won, and they would normally talk about things that were within their own control agency. It's like when I first bought Park Place, when I got my first monopoly, when I did this, and they did not mention the coin flip. And so that is fundamental attribution error in play, which is the tendency we have when it comes to our own lives to overestimate our own agency and actions and underestimate environmental factors or those things around. And to the second part of your question, in terms of how that sort of can play out or be damaging, it is this notion of, well, if you're always thinking that it's in your control and that you're sort of in charge of your own life and every outcome is because of what you're doing, one, when you fail, as we often do, it can be really difficult and debilitating and depressing. And even when maybe you succeed, but you see others who have not, you have a tendency to be less compassionate for them, and we can talk about it later, but the ways in which it manifests itself in society are pretty daunting and damaging. I think it's interesting, just in that last part that you just said, and even how it manifests itself inside of the game that you just described, the taking of more pretzels, the pounding of the sound of the Rolls-Royce versus the shoe and how forceful that is. And those are things that if you probably asked either of the participants, there's probably things that are beyond most conscious attention. And so there are things that are happening. And so you parlay that out, and again, you can't always expand things out to the larger piece of this, but you parlay that out, and you think about the impact that has on just our everyday behaviors, the way that we show up in the world or don't show up in the world, and the attribution of, well, they're just that way, and they're not being forceful enough. They're not doing this. If they were just do X, then they would achieve Y, and yet we don't understand that there's aspects of that that are embedded inside of the actual component itself. Yeah. Although I would also say that empathy is a door that swings both ways. And so what I also learned from digging into this was I used to think that people who were uncaring to the poor, people who were successful in uncaring to the poor, uncaring to others, they were just jerks. And increasingly I've said, well, actually, there's some interesting psychology here is to sort of why we're behaving the way that we are. And to your point, it isn't always conscious. It's not always a conscious choice to eat more pretzels than someone else or whatever, but it is something that we are not aware of our own tendencies. We're not aware that this is happening. And the beautiful thing about attribution is that when you get into a situation where you can ask people to reflect on their own lives, and you do it in a way that's not antagonistic, basically saying, calling people out for being privileged, but you do it in a way in which they can basically see for themselves, then they can't unsee what they've seen, right? And they see people in the world in a different way. And that's what I hope to do, like not be judgy about sort of people who are unkind or uncaring or maybe have a different worldview than I do about this, but to basically just through inquiry and through reflection, find opportunities for people who are like, "Ah, yeah, I didn't think about that." Bob, how common is this? How common is this attribution here? I guess I'm sort of wondering how big of a deal of it, because I mean, I am pretty sure that every bit of my success is because I worked really hard. Maybe wasn't the case for someone else, but I'm being sarcastic, please. But so I've had conversations with people where they're like, "Well, that might apply to someone else, but no, really, for me, I really did. This really was just my own hard work." How big of a deal is this? How common is this attribution era? Yeah, so years ago, I did a study with Public Agenda where we did a couple of things. When we went around the country and talked to people about their dreams, then what they thought attributed to them, and that was really just an incredible experience to sort of have people open up that way. But we also followed up with a national survey, and we asked this question, "Do you think that your success is largely through your own making or through the efforts of others?" And half the country basically said it was because of what you do. But even within that, then we did another question where we asked people to rank what factors were absolutely essential to moving it up or having success in life. And hard work was number one, regardless of your political affiliation, regardless of whatever. So everyone thinks that hard work is the most important thing. What happens after that is divided by gender, political views, things like that. But interestingly, most people think that luck is at the bottom and the randomness of life. And we know that's certainly not the case. We don't choose our parents, we don't choose where we grow up, all these kinds of things. I just read and reviewed a book called The Random Factor by Mark Rank, which was really fascinating and spoke to him about this. And we definitely under appreciate the role of luck in our lives. So one, if you start with the fact that everyone thinks that hard work is most important, and other factors are significantly less than that, and if you think that half the country believes that hard work is the real driver relative to other things, then you see that this is a very common belief, right? And so what does it mean in practice? Well, it affects the way in which we think about who the rules apply to, it affects the way in which we think for support for certain government programs, it affects the way in which we think about how our success is or isn't tied to others in terms of zero or some thinking. If I give you a hand up because you need it, that means that I'm somehow worse off, which is not the case, right? Even something is counterintuitive as, and this was shown in research that was done by Rachel Rotan, who I think is still at the University of Toronto, but she had found that people who had gone through a difficult life experience were less compassionate to people going through that same difficult life experience. So for example, if you quit smoking, you were less compassionate to someone trying to quit smoking but unable to do so than someone who had never smoked before. And if you think about why and going back to this question of attribution, if you quit smoking, what do most of your friends tell you, "Oh my gosh, that must have been so hard. How did you do it? You must have an incredible willpower to overcome that addiction." They're not talking about the laws that made it harder to smoke in public places, they're not talking about the person who invented an incorrect gum, they're not talking about the support that you had from your family. And that applied to people who had been unemployed but found a job, less compassionate people looking for a job. It was just really fascinating. When I talk to her about this and try to figure out what hypothesis for why that was, it's this idea that if you have achieved something, maybe you've moved up the economic ladder. And you almost have to think that you did it on your own. Otherwise your hold on that rung is tenuous because if you think it was a combination of luck or other factors that those things then could immediately reverse and now you could be falling down. And so it is this sort of narrative that we sort of tell and it's often reinforced in culture and in stories and in movies and in books. One of the things you talk about is headwinds and tailwinds and this idea that the facts of our lives are one thing but when we look back we tell ourselves stories about our lives. And can you go in a little bit and just talk about, because I think what you're also saying in that situation is when that person who stopped smoking or got that job is looking back, what do they remember versus what actually happened? Can you talk a little bit about headwinds and tailwinds? Yeah, so I'm going to separate those two things for a second. So I refer to, I think it was Daniel Kahneman had said this idea of there is their lived self and their remembered self and the lived self is about a stranger to me. And so there's the story that we tell about our lives, this narrative that forms over the course of who we are and that story is really powerful. And so the story is informed by life events and the things we remember and the things that we don't. And the work you're referring to about headwinds and tailwinds was from Shai Dawdadei and I think Tom's Jillovich and it was this idea of anyone who's ever gone for a run or bike ride, and you're out there, you're generally going to be more aware of wind blowing in your face, a headwind than when the wind is at your back. And that metaphor applies to way in which we think about our life. We are just more attuned to our struggles and less attuned to the help that we get. And I'll give you a good example of how this played out for me. So I've written a couple of children's books and it's all by accident. And so the accident began because Dawdadei, who I knew from teaching together at Parsons in the new school, had forged me an article about his research on headwinds and tailwinds. It was written by Maria Conakova and it was in the New Yorker and it was called "America Surprising Views and Equality." And the article ends by where she asks Dawdadei what in his own life he does to reflect his research. And he says, "I can tell you what I don't do is I don't read the little engine that could to my kids because some kids and some engines can't and it's not fair." And I saw that and I was like, you know, at first my, that seems sort of harsh. I mean, you know, the whole message behind the little engine that could is, "I think I can. I think I can. I think I can." And you want kids to believe in themselves and to work hard to get over amounts and stuff like that. But at the same time, I saw what he was, where he was going with it, which is that, you know, hey, we're all on different tracks. And some tracks are, you know, it's deeper, difficult, have more things that fall on and than others. And so I just asked myself what a different version of that story would be like, right? And so I, you know, one day just scribbled down the note, sorry, the story. I asked my kids what they thought of it. They said, "It seems pretty good." I, you know, talked to a couple of people who were kids authors. They were like, you know, maybe, you know, and they said that then I might ask intellectual property rights because of the original. And so I co-called Penguin and, you know, they said, send in his email, what are you thinking about? A couple months went by, didn't hear from them, followed up again. And, and then I said, it's the manuscript. I did that. They said, would you have a meeting with our author or, sorry, our editor and children's books? I'm like, yes, sure. And I thought they were going to tell me you can't do certain things. You can't have it so close to the original. And instead they said, well, as luck would have it, it's the 90th anniversary of the original. And we've been waiting for, we've been looking for ways to tell an alternative version of this. And they're like, would you let us publish your book? And I was like, no, no, no, no, I'm too busy. I was like, yeah, sure. And so, and so just to sort of tell, to keep the story going a little bit. And there were sort of like, you know, things that were bad and good, like, you know, it was scheduled to come out during the pandemic. But then at one point, you know, literally it was on a, on a ship on a containers and the containers fell into the ocean to be lost forever. What? Yeah. Never to be found. So there's fish reading my book somewhere, right? And so, so delayed the publication, which then put it closer to the end of, of that, which made me, allowed me to do more things through a connection I had, I made a contact with someone at CBS Sunday morning. They featured it became a New York Times bestseller. And now I'm able to write two more books. Now I tell you that story, because when I tell that story to people, there are some who will be like, man, you worked so hard to publish that book. It's amazing, you know, you should be so proud of it and I am and I did. But I'm like, did you not hear the other parts of the story? Like I don't, I don't read the book, I don't write a book unless someone sends me an article. It's not successful unless it's the, you know, it does get published, you know, except for the fact that it was the 90th anniversary of the original, so timing, right? Even something bad like, you know, it being lost in the ocean gives an opportunity for me to do more things when it comes out. And then it's through a social connection and social capital that allows me to, you know, get some of the coverage that got. And so it's, it's how do we tell these stories about our success in ways in which you can see the fullness of it and that it's rich. It doesn't diminish someone's effort. It actually makes it more whole. Also it shows gratitude to others and the collective effort it makes for success. And so, you know, that's what this is, you know, really trying to do is it's never trying to say like, hey, someone doesn't work hard or that's not important. It's like, hey, there's a lot of people working hard to make everyone's, you know, life a little bit better. And let's just sort of look around and acknowledge these things. And also acknowledge that like, there's also some bad stuff that happens. And that's not anyone's fault. And yeah, and it's, it's, whenever I have the conversations with people, it's generally like, you know, people leave feeling, you know, more appreciative, more grateful, more understanding than, you know, before we started talking. I hope they do. You've done a great job of telling that story in a way that just feels so accessible. That I'm hoping that more people are going to get the nuance in this, you brought that up earlier on that this is a problem. You also wrote about there were three important foundations in our world today that viewing them with through this lens of attribution might help us. You talked about education and climate change and racism. And could we spend a couple of minutes on at least one of those, Bob? Because because I love the fact that you actually blew it up to, wow, here's a world level crisis that after, you know, if we understood the attribution elements, we might actually do a better job at solving for this. Yeah. So, yeah. So, I mean, I'll tell you a story around. So this is sort of related to race and class, right? How we talk about these really difficult conversations in our country in the ways in which we can sort of be open to them. And I don't know if you've seen, you know, some of the exercises that happen in classrooms around sort of like a privilege walks and things along those lines where essentially you're asking, you know, students to if you've had this happen to you that was positive, take a step forward. No. And if you've had this, take a step back. And that ends up, in my opinion, being a very divisive exercise, you know, in terms of people who are like, you know, thinking about themselves in ways in which they feel bad or guilty about if they had success or they feel bad if they're the ones in the back, right? And what I try to do is to just have more sort of individual reflection and conversations about this so that we can understand our life and questions around class and privilege and race in ways in which we understand them. And I'll give you an example, this tie is to, you know, to both race and to education. Years ago, I had the opportunity to give the commencement address at my alma mater where I did my undergrad at Penn State. And as part of that, I got access to one of the, to the university librarian and researcher. And I just wanted to understand a couple of things. And part of what I was going to talk about was a grateful I was to the institution in recognizing teachers and all the things that allowed me to sort of be on that stage that day. And as part of that, I had always been particularly proud that I had gone to a land grant university, right? And land grants as I understood them was something that was the moral act was signed, you know, into law by Abraham Lincoln, you know, obviously a great sort of champion of equality. And it was designed to create more access to higher education for people beyond sort of the wealthy and, and that's then, and universities like Penn State and Michigan State and Cornell and so many others, you know, were basically funded on that premise. But I didn't really sort of question how the land was granted. And through my conversation with this librarian, I learned that while in some cases land within a state was just appropriated, in many cases, if not most cases, what had happened was the federal government had taken the land from the Native Americans in Arizona and New Mexico, and then they gave that land in proportions to different states to then sell off to create their endowment. And I was, that was sort of a story where it's like, man, this is something I felt good about that now I feel not so good about, right? Yeah. Wow. But I'm like, what is my responsibility? Like, I didn't take the land, but I benefited from it. And so I was having this conversation one day on an interview on my podcast with Natasha Tretheway, who was former U.S. poet laureate and who had written this wonderful book on Memorial Drive, which was also a reflection on, you know, race and things along those lines. And when I told her the story about the land grant, she just sort of paused and in a sort of wonderful way, she just said, like, you know, isn't that wonderful that you know that now? That I now can walk around the world with a fuller story to tell, you know? And, you know, it doesn't excuse what happened historically. But as someone living in the present, it allows that story to make more sense to me. And for me, now I want to tell that story so people can appreciate their connection to Native Americans, their connection to how they were wronged in different ways, and to also be able to have an appreciation for how nuanced so many stories that we have. And when we instead sort of try to make some of these conversations so political and so divisive, instead of allowing sort of the nuance that attribution brings to it, you know, it just it doesn't help our country. It doesn't help ourselves. And one of the things that also gets and fogs so much of this stuff up and makes it difficult is, you know, we all, I'm sure you're familiar with the idea of just world, right? So we all have this sort of just world sort of thing. So we want the world to be fair. And so the way in which we then figure out ways to tell the story of fairness affects actually whether we go on to create a more fair world. And in the question of attribution, if the reason why the world is fair is simply because of the way we work, then that actually and ironically creates a less fair world. When we talked about the question of how we end up where we are in a more nuanced way of attribution, then it creates a more just world because we're able to act according to what we're learning and feeling about how the world is and why it works the way it does for us. Yeah, I think a couple of the things that you just touched on are really interesting is we think about the psychology that we have as people and just this idea of learning more that makes you feel uncomfortable. And we too often avoid that because of that uncomfortable that I don't want to know about the land grant and how that came about because I had a positive view of this and now that is being diminished. And as part of that diminishing, it's part of it affects me as to who I am. But I love this kind of reframing. Isn't that wonderful that now you have this new knowledge that you can bring forth in whatever way you have? And I think just even that reframing of those pieces because too often, and I'm making a judgmental piece here, too often I believe that I see it myself is I don't click on that news article or I don't click on that social media thread or I don't talk to that person because I'm afraid at some deeper level that they're going to throw my worldview a skew and even if it's a little bit and that's going to cause me angst and that it keeps me from learning. It keeps me from exploring the world and I think having just that change in mindset is just so important to making us be open to some of this more learning about the world. So let me try a little thought experiment for you or for the listeners, right? So so many people love the movie Rocky, right? And the several that came after, right? Because he represents this sort of underdog story who we clearly worked really, really hard to get where he was. And so that's an awesome, that itself is a great story. Rocky works hard and he wins it, you know, whatever. But if you go back and watch, especially Rocky, the first one, and I've done this, I worked with a company where we recut the trailer to Rocky. And instead of just like all of the workout scenes, we showed other stuff, right? And so the film opens because some other boxer gets hurt and they need to replace him. And then when they're trying to find someone, they need someone who's local, so they're looking for a Philadelphia kid and they're looking for someone with a good name. And so the Italian stallion is sort of jumps out because this boxing match is going to occur on July 4th. And so they're like looking for someone who's a sort of ancestor of Christopher Columbus. And then he gets selected. He actually turns down the fight and the promoter has to convince him to take it. Then he takes the fight, his lone shark boss gives him some money so he doesn't have to work so he can train, right? Poly lets him come in every day to sort of pound the meat, right? So he's working hard, but he's also leaving with a stake that Poly presumably has lifted, you know, and given to him, right? He then sort of goes on and he's sort of training. Obviously, Mick, you know, trains him. So he's got a trainer. He's got people working in his corner. Adrian is so supportive, so, you know, helpful. So inspiration, even the night before where he's like afraid, you know, and so vulnerable, she's lifting him up. And then he's like running through the streets of Philadelphia where people are cheering him on, right? And so now I ask you, which of those stories is a better story? You know, to see all of these people, you know, and all of these things that made his success possible, which by the way, he doesn't even win that first fight, right? And so to me, like that's why the, so we can remember Rocky is this sort of like, man, he really worked hard and that was great, but that's not what the movie was. The movie was all this other stuff. And so I think most people, and I would hope that when they stop to think, they're like, wow, that's even a better movie than I thought. That is a great reflection on a great way of reframing a movie that I've always had in my mind as it's the hard work story with a little bit of luck. But you paint it in a beautiful way. You mentioned, you used a term earlier that I wanted to get back to this just world, this belief in a just world. And can you tell us a little bit more about that and how pervasive that is? Because I mean, we could get into a whole nother hour just on free will. We're not going to do that, but just if you could sort of tee up the belief in a just world concept and where we see it playing out in the world. Yeah, and it's funny, I think it was Kurt said earlier, like sometimes you avoid conversations because you don't want it to sort of change your view of the world. I've not opened Robert Sapolsky's new book, which essentially makes the point, which essentially sort of makes like there's no such thing as free will, right? So but anyways, I think just world is something that sort of allows us to go throughout our life and not feel so overwhelmed by the pain and suffering that exists, right? And so you have to in some ways tell a story that makes the bad stuff make sense. And it's the choice of the story we tell that's important. And so in the beginning of our discussion, I was talking about how I was going through feeling really guilty about, you know, where I was relative to others, right? And you know, I could have just told a story where like, well, they didn't choose to go to college. That's their fault, you know, or they didn't choose to do this. That's their fault. But I love my family and I love my friends. And I didn't, that's not a healthy way to sort of go through life with them. But I see families where that is the dynamic, right? And so I wanted to understand it. And so even thinking back, like my, my sisters had health issues that I haven't had, right? And that's gotten in our way. And a little tiny story, right? Like so when I was young, I used to like to read and I wore glasses and I wasn't reading like Tulsa. I was reading like box scores for the Red Sox, right? But I was just, I was reading, but, but my mom, she gave me this nickname of like my little professor, right? Wow. And she didn't know any professors, you know, she didn't know what it, what it, what that even meant. But there was an expectation for whatever reason very early that I was going to college. And I would even remember and I feel so bad and it wasn't intentional. But I know I would hear like, he's the smart one, right? And my brother and sister are smart, smart in ways that blow me away. Like the fact that he can take away, take it apart, a car engine and put it back together. We had thinking about it, right? And so even these kinds of labels can be, you know, challenging. But the fact that I had this expectation early on, right, was this sort of another contributing factor to, well, what if my brother, who also wore glasses for a period of time was called the little professor, what would that have done, you know? And so, so I think that the idea of just world is all around us. And I think that we avoid hard reflection because the world is complicated and there is bad stuff that's out there. And for you to sort of enjoy aspects of your life while you know others are not, is hard. And so we need to find a way to make sense of it. And I'm here to say that I think there's a way to make sense of it that is more nuanced and isn't putting our head in the sand about sort of the complicated bagories of life. Yeah, there's so much that we could probably unpack there and just even looking at many of the conflicts that are going on in the world today and when there are sides that are chosen and how do they justify their actions versus others and the reasoning behind different things. I mean, you can just look at any of the wars that are going on right now or a variety of other factors in US politics or a number of different things that we'll invite you back and hopefully come back and we might get into that. But one of the things that I want to come back, I want to come back. And so for our listeners to have some actionable things that they can take out of this, and you suggest a few things at the end of this attribution article, among them, which among them stand out as being necessary kind of for our world, and you talk about tell more stories, judge less, and work with other people's beliefs. Could you expand on what you, each of those a little bit, just to help our listeners to say, here are some things that I might be able to do just in the immediate future to be a little better at this. Yeah. So yeah, I think sort of judge less and tell better stories. I mean, I think you give an example looping into both of those. I think like you could walk by someone, say who clearly was down on their lock, you know, maybe they're homeless, maybe they're whatever, right? And you can choose to do nothing. Just walk by, you know, not give it a second thought. Or maybe you give a little bit of money. But I think one of the more powerful things you could do is to pause and take a second to sort of embrace their humanity and just ask your question, like, I wonder how they ended up here. You know, I wonder what must have happened because that person is a son or a daughter and was a student and was all of the things that you were at some point to. And that kind of, you know, questioning and trying to understand someone else's journey, I think is really important. I think the other thing about sort of judging less and telling stories is our ability to show up and be vulnerable for ourselves. You know, like I have no qualms sort of like talking about aspects of my life that did not go particularly well or places where people were able to help me. And I see now when I teach, for example, at City College, where we've just started a social mobility lab, right? And when I, and I enter the room and I begin by telling some of my story and it creates an opportunity for everyone to feel like they belong, like they're seen, and they can be in that room with the fullness of their lived experience. And then you tell little stories about why this is important. Like my new children's book is called America's Dreaming, and that's about sort of like how important it is to feel welcome and feel like you belong. And part of this idea of attribution is that there's also sort of the math you affect the play, things compound, right? And so imagine you're a kid and you don't feel welcomed in a classroom. And so now you sit in the back of the class. And we know through studies that people in the back of the class get called on less. And people get called on less often don't do as well in school. And then you don't do well in school and what happens. And so I think that there are these ways in which we can be, we can embrace others instead of judge them. We can be vulnerable for else. We can learn, try to learn other people's stories and tell our own stories in different ways. And, you know, part of what I appreciate about your podcast and part of what I do in my own work, what we're trying to do in the social mobility lab is there is a wealth of information about how we think, right? And so often it's locked in papers or if it maybe gets into the mainstream and through a book or a TED talk, but most of America does not read, you know, or watch TED talks. And so how do we translate this into other things, whether it's daily actions, whether it's a children's book, whether it's the way we tell stories like Rocky. I mean, I think that the part of for your listeners is how do we find ways to make the work more accessible and how do we translate it so it can have impact on people's lives, where you're like, oh my gosh, that is something we definitely should make sure that everyone knows and that success of the work in behavioral sciences isn't about publication. It's about giving someone the tools to change behaviors to make society a little bit better. I love that you're so optimistic about this. I really do. I see this in your work where you're at the same time, you're kind of down in the muck with real significant societal problems. You're also very optimistic. I really appreciate that about your Bob. Yeah, you mentioned the word muck in my first book, which is a collection of essays called Action Speak Loud is keeping our promise for a better world. The journalist Juan Williams wrote the forward to that. And it was a collection of 32 people who were addressing different issues, ranging from Jimmy Carter, who was writing about PDs to Richard Costaldo, who was one of the first students shot at Columbine, writing about violence. And he categorized people in the book who put their hands in the muck in my hair of life, looking to do and pull out something better. And yeah, you get proximate these issues and it should be inspiring to sort of want to try to make the world a better place. It is. But now we want to find out if the world would be a better place, if you happen to be stranded on a desert island for a year, and you got to choose two musicians, two musical artists, catalogs, not the individuals, but the music that they make, which two would you take with you? Yeah, that's so tough. I would probably say, okay, these are going to seem strange. I would say... Try us. Yeah. I would say Neil Diamond and Tracy Chapman. Those are great. What's strange about that? So generous. And I'm also emphasizing early Neil Diamond, but I'll actually, although let me take that back, because the album that he had done that was produced by Rick Rubin was brilliant. But I love music where you can hear the lyrics, and where the lyrics are important. And that's... I'd reference Joy, a lot of Kuno we were talking before we started the interview. I mean, you know, these things so often the musicians, I think when they're doing it well, they are just trying to make sense out of their own life. And then they put something out there that helps other people make sense out of their life. I mean, they're not different from behavioral scientists, right? No, just trying to understand the human condition and put it out there in a way that reflects the fullness of it that other people can identify with. And so the ability to go and sort of listen to people who are talking about their life experiences in ways that, yes, are serious, but also hopeful and at times full of joy, I think is a good way to spend some easy listening time on an island. Well, I'm going to agree with you on the Neil Diamond on like the Stones album or coming to America or Hot August Night. I'm not sure if Cherry Cherry or Sweet Caroline is diving deep into his personality or this thing that he was struggling with. I will say this, and it may be closing soon. There was recently... It's called The Beautiful Noise. There's Neil Diamond, sort of a musical on Broadway. It talked about him working through his life and his music through therapy sessions. And you saw where all of these things came from and why he wrote these songs. And yeah, so I really love, like, you know, I am, I said in Brooklyn Roads and those kinds of things where he's going through the exact stuff that we were talking about, like trying to figure out how he fits in and is he worth it or is he an imposter and all of these kinds of things. And again, doing so with great vulnerability, which, again, he sort of revisits in sort of his later music with Rick Rubin. But yeah, some of it's just fun. Well, and I'm not, I don't know much of Neil Diamond's deeper catalog. I know the hits, but the Tracy Chapman is, when you mentioned her, I'm going, "Oh, that's a storyteller." I mean, Tracy is what I would say from a musician is one of the best storytellers out there from all of that. And it's so great to see the resurgence that she's had because of, is it Luke Combs? I can't even know who we did that. She's getting that resurgence of people and hopefully a much younger generation who's able to appreciate some of that. And so yeah, it's fantastic. Well, I think another aspect to that was really great was that when he first covered the song, there was a mini backlash where people were saying that this white country singer should not be sort of appropriating her music, right? Yeah. You're talking about fast car. Yeah, fast car, yeah. And she immediately came out and said, "No, I think it's great. I love it." And it's because that story that she was telling was universal, that like, "Hey, I'm struggling. How do I get out?" And that's something, whether you're white or black or any other sort of ethnic or race or gender, I mean, it's a universal sort of feeling that we have. And so many of our struggles are universal. And yet we don't sort of recognize their universality or we think that only certain people can tell those stories. And the more that we tell stories with vulnerability and nuance and proper attribution, it just creates a stronger society, I think. Yeah. And I think all of that is true. And I did hear Luke talk about at one point, like, that was for a period of his childhood. That was his go-to song because he resonated with him. That's right. I can ever say that. Yeah. And that's the beauty of music, right? You know, it's like, if someone writes it and they write it to figure out what they're going through and someone's like, "Yeah, me too." And it was really beautiful in the Grammy performance that they did, where you saw his reverence, right? And it was just the magical moment, you know? Yeah. So. George Shirley, along those lines, George Shirley, the great black opera tenor, was once asked, "Well, what right do you have to be singing these Italian and European operas with how you grew up?" And he's like, "I just totally connected the music." And there's no, there's no appropriation going on. This is just, I just completely connect to it and I love it. And so I'm just doing what I love. And then the reverse was spun on him, like, "Well, what do you think about white people singing the African American spirituals?" And he's like, "If they connect to it, that's great." Yeah. Well, I'll tell you a funny story or an interesting story, I should say, is that with my latest book, it's called, you know, "America's Dreaming" and in the main characters in America, right? It's based off of a difficult move that I had moving from Boston to Pennsylvania, right? Where I was going from a place where the letter R doesn't seem to exist to a place where, like, every word seems to have three or four. So I sounded and looked different than the other kids, right? Wow. And so, but, you know, through a very kind teacher by the name of Mr. Downs and, you know, whatever I was able to acclimate a little bit, but I've always felt like I don't quite sort of belong where I am for various reasons. When I was writing the story, I was like, "I want to call the character America." And I want to do that because I think this is something universal. And then I was thinking about in the earlier drafts that I was like, "All right, the character, America sounds like that's probably a girl's name." And then I was like, "Oh, instead of moving from Boston to PA, maybe I'll just sort of tell a story where they're moving from another country or whatever." And then there were some questions to whether, even though it was based off my experience, I would be writing where the lead character is a girl or an immigrant. And I understood that and I was like, "Okay, let me think about it." And then I made the choice and the work around that the character would be named America and we would never see them. And it really changed the book in a great way because now you're seeing the first line of the book is, "Have you ever felt all alone on the crowd?" And all you see is America's tiny shadow in a sea of people walking into a school. And it led to incredible illustrations by Lister de Flong, who was just tremendous. And it allowed this sort of change in perspective. And to get away from the who can tell whose story and instead focus on this is an important story that we all probably can relate to. And we need to sort of think about how we choose to welcome people in our society, regardless of where they look like or where they come from. Because if they're not made to feel welcome, it will affect not just them, but our country as a whole. And with that, we are so grateful. Bob, thank you so much for being a guest on "Behavior Groups" today. It's a real pleasure. Thank you for having me on and good luck to all the good stuff you're putting out in the world as well. Welcome to our Grooving Session where Tim and I share ideas on what we learned from our discussion with Bob, have a free-flowing conversation and groove on whatever else comes into our misattributing brains. Oh, nice. Yeah. Yeah, it's the misattribution that gets us hung up, doesn't it? Yeah, I mean, we attribute things all the time. It's our natural set way that we look at the world. It's like, oh, that happened, that was had a cause and the cause was set because of these things. And that's just the way that we as humans see that world. It is when we have this natural tendency and often just, you know, we're wrong about those attributions that leads us into this world where that's not a good thing. Okay, so let me get this straight. Are you saying that my successes are not completely because of my own hard work? I mean, I drove everything that I did in my life. I made all those decisions. I did all that work. I'm the one that got me here. Isn't that right? And I'm also saying with that same thing, yes, and the fact that you aren't, you know, a multimillionaire and that you don't have aren't selling out stadiums across the globe are not just because you didn't work hard and do that. They have other external factors that are leading to those as well. So it's not just this idea that, hey, our successes can all be attributed to the hard work and smarts and diligence and all of those things that I do. It's also that, you know, we may not have achieved everything that we wanted to achieve. And that's not because we didn't do the things that we needed to do. It's just sometimes outside circumstances, luck play a part in all of that. Yeah, I'd like to think about the environment and our context conspiring to sort of make our lives more real because all of our plans don't always work out. But it's basically, it's not that I didn't work hard or that I didn't get good grades, but it's that that wasn't actually the main driver of my success. Well, it was a driver. I mean, I don't think we should miss a tribute thing is like, you know, if you just sit on your ass all day and, you know, eat bonbons and watch television and you want to be the CEO of a company or run a marathon or, you know, be do whatever else that you want to achieve. Well, you know what, you need to put some work into each of those things. Yeah. What I think the important level of this is that, and I think this comes both, it comes in all walks of life, right? So the person who is very successful ends up attributing that more to their hard work in different things than to some of the external circumstances. The person who isn't as successful attributes their own lack of success to all of those external factors that are going on. And I think in between they both look at the other and point fingers and say they got there because they were lucky or they are stuck there because they're not working hard enough. And this is where I think that Annie Duke's thinking and bets can actually come in hand occurred. This is where we get away from this duo thinking, this idea that it's either 100% or zero percent. Life is much more complicated than that. We don't need to think about everything that we do in our life as I was 100% in or 100% out. Sometimes I'm like, well, it's, this is probably a 70% good idea and I'm like 10% neutral, 20% maybe not a great idea. But I'm going to do it anyway because I think the odds are in my favor. But that doesn't mean that it's going to always be perfect. Well, and Annie also talks about this process, this idea that we make a decision, we take an action and then there's a result. And what we forget is that in between that action or somewhere in the in between that decision and the outcome, there's this element of luck or circumstances that come into play. And as a poker player, she knew that she knew like there was this, all right, the my best choice is to go all in here. But you know, there's a little bit of luck about what that next card is going to be turning up and that I think informed the way that she thinks. And I think it's a really good way of looking at the world because, you know, everything we do has that component that, you know, two people doing exactly the same things can get very different outcomes, exactly. And that leads me to the second thing that I wanted to talk about. I loved our discussion with Bob when he went into Rocky, right? And this I'd never looked at the movie Rocky from the perspective of how much support did he get? How much luck came into into play? How many circumstances were leaning in his favor at the moment that they needed to? Well, in the fact that he had, you know, he had a village helping him. There was this whole element of community that went beyond him. So yeah, you want to talk through that? I think that there's a couple of things that are worth pointing out and things that really stood out to me. And of course, let's just say that he starts because the boxer who was going to do the fight drops out and they need to replace him. And so there's this instant element of luck, right? But there's a couple of things. The replacement needs to be someone who's local and the Italian stallion as a name jumps out. So sure, he's got good branding, but he's got this incredible luck and circumstance going on that I think we often overlook, oh my gosh, I was the person that got picked to do something because I was at the right place at the right time. Yeah, the boxing match was going to happen on July 4th. They wanted to have that kind of local hometown person there to promote it. So he just, he had the branding, but it got lucky to that part, right? Yeah. And then yeah, go ahead. Well, the other big thing is the support, right? There's these lucky circumstantial kinds of things, but then there's this support. He's got Mick as the trainer, right, who is incredibly supportive. You don't even know if he's getting paid, right? There's the impression that Mick joins on as a supporter because, you know, he just really loves Rocky's vibe and Adrian, like his girlfriend is incredibly supportive. She never once winces or says, you shouldn't be doing this. And you just think, wow, this is, these are really important circumstantial supporting situations. Well, even beyond that, he had the loan shark who gave him money. So he didn't have to work, right there in and granted there's a quick quote on that. But there is this element that he knew somebody that could do that. There are those aspects in him, right? Yeah. Yeah. So I think that it was really great to walk through that. And it was a beautiful way of thinking about the great American hero, Sylvester Stallone's Rocky as being somebody who actually got a lot of support, got a lot of good luck. Yeah. Now, the interesting thing, he worked really hard, right? He practiced. He trained. He ran. He did those, you know, he ran up those stairs. He did the jump rope. He did all of that kind of stuff. He did. And the best thing about this is, look, Rocky won. He didn't win. He lost, you know? That's right. That's right. But it wasn't until Rocky too when he wins. So again, he had all of those factors. He worked really hard. He got the luck of everything and yet the outcome, you know, he lost. So if on the outside, you could have said, look, he lost. He obviously didn't work hard enough, you know? Or he got this huge fight of his career, you know, he didn't put any work in. And yeah. He was a failure. Yeah. Yeah. Okay. What can we do about this? I think that that is sort of the next thing that I want to talk about. What can we do when it comes to attribution in our individual lives? You already mentioned like thinking in bets, that idea of, you know, bringing up this perspective of, hey, it's not always black and white, different things. I think it's part of that. We need to be reflective and curious about our own life. So particularly about those things that we take for granted, like that's the way it is. Well, is it? Is that really the way it is? Yeah. Yeah. I would also like to think that when you're not just thinking about yourself, but you're thinking about other people, maybe pause and ask like, how did they get here? How did they get to the place that they're at? Either this place of tremendous success or not success, right? Give people some grace. Yeah. It gives people grace. It reminds me, Brad Chuck talked about that in our conversation with Brad, which is way, way many, many, many episodes ago in our first 50, I believe. Yeah, but we don't really know everybody's entire story. So let's open it up and we could use this thinking in bets idea to think about there's other possible explanations for what has happened in their life to get them to hear than then what is coming to mind right away. You know, one of my favorite all time things is Hanlon's razor, which is being never attribute to malice that which is adequately explained by stupidity. Say that again. You got to say that one more time. Hanlon's razor never attribute to malice that which is adequately explained by stupidity. So much of, you know, what we think other people are doing maliciously for us might just because hey, they're stupid or, you know, yeah. That guy that cut me off on driving down the freeway, he was an idiot. Well, we don't know the whole story. Maybe he was. Maybe he was, you know, not paying attention. Maybe he was on his cell phone, being completely stupid in the way that he was driving. But it wasn't malicious against you. He wasn't trying to piss you off and that the the attribution of he's just he's just trying to mess with me. No. He's just distracted. You know, it's not going to have to be about stupidity. It can just be like a number of other factors. So never attribute to malice that which can be adequately explained by something else. And I think that's probably a better way. And that is and that's a great way of thinking about attribution that we don't necessarily have to agree with the conclusion that we just jumped to. Okay. Any other thoughts, Kurt? I think we can wrap that up our our work probably good with our grooving session on Bob McKinnon. What do you think? I'd agree. I'm always so grateful to have conversations with people who are doing good work and Bob is absolutely one of those guys. We'd like to invite Grovers to use a moment between now and your next podcast to leave us a short review or give us a quick rating. We are always grateful for comments and reviews and ratings because Apple and Spotify algorithms rely on those numbers of reviews and the number of ratings that we get to help determine which podcast gets shown to people in their search results. So if you're not subscribed to our newsletter, by the way, please do so. If you've not actually given us a reviewer rating, please do so and you can find our newsletter on the website. Right. So another way of thinking about this is that all the hard work that Tim and I do for this podcast are going to be the success of this is all down to the you giving a review because that'll change the algorithm which will be lucky for us that now we'll get seen by millions of other people, right? So anyway, no, not putting all this effort, you know, we're not successful as we want to be because people don't write damn reviews. That's not what I'm saying, but you know, be very grateful and ratings do make a big difference and we would very much appreciate anything that you do. For now, we would like to just encourage you to think about how you're attributing success or other not success out in the world and how the fundamental attribution error might be getting in your way or someone else's and use that information this week to go out and find your group. (upbeat music)