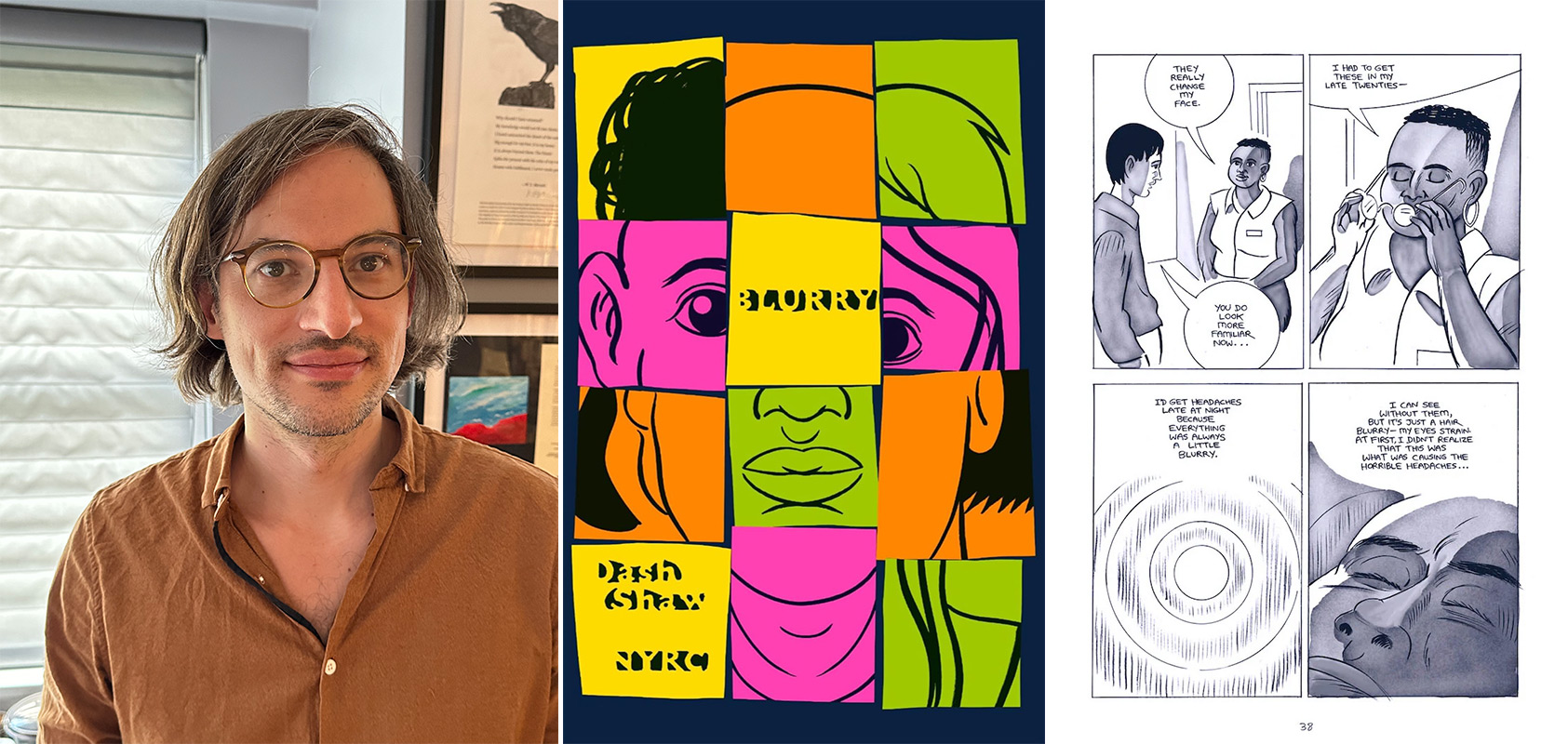

Cartoonist and animator Dash Shaw returns to the show to celebrate his phenomenal new graphic novel, BLURRY (New York Review Comics). We talk about the decompressed mode he brought to this book, the turning points we encounter in the most mundane situations, his focus on the microscopic moments of doubt we have between two very similar things, and how he settled on the idea of structuring the book around nested stories (& figured out to thread them together by the end). We get into the 2x2 panel regularity of every page of Blurry and how that allowed him to build the book, how the experience of making a Clue miniseries changed his comics-making process, and how Blurry felt like he'd been playing a video game for a long time and then discovered a bonus level. We also discuss his film-making process and how that contrasts with the isolation of making comics, the ways his work tends toward collage, why naturalistic dialogue is another form of stylization, what it was like to grow up in a comics-friendly house, and a lot more. Follow Dash on Instagram • More info at our site • Support The Virtual Memories Show via Patreon or Paypal and via our e-newsletter

The Virtual Memories Show

Episode 602 - Dash Shaw

(upbeat music) - Welcome to The Virtual Memories Show. I'm your host, Gil Roth, and we're here to preserve and promote culture one weekly conversation at a time. You can subscribe to The Virtual Memories Show through iTunes, Spotify, YouTube, Google Play, and a whole bunch of other venues. Just visit our sites, chimeraobscura.com/vm or vmspod.com to find more information, along with our RSS feed. And follow the show on Twitter and Instagram @VMSPod. Well, I am limping into the unofficial end of summer, but at least I made it. Last week got kind of heavy. It involved a drive up to Boston, to moderate a biotech panel, then out to Cape Cod on Thursday morning from there, well fleet specifically to record with next week's guest. And that meant I had a six hour drive home that afternoon into evening, which while at the living crap out of me, I just spent too much time by myself in a car, and it took me a while to recover from that mentally. Physically it was okay, but anyway, I turned around and recorded the following week show in New York City on Saturday. So, yeah, I'm functional enough now. I mean, I got up at 3 a.m. with anxiety about this morning's virtual presentation. I had to give to Pfizer, and then there was this federal agency I had to talk with in the afternoon. And there was the bear that Benny and I encountered on our morning walkies, but anyway, Labor Day weekend is coming up. So, let's say this is the last show of the summer, dive right into it. My guess this time is Dash Shaw, who has a mind-blowingly good new graphic novel out. It's called "Blurry BLU, R-R-Y." It's from New York Review Books comics. Blurry is a, it's a strangely disconcerting book. And it's one that I just enjoy tremendously. Dash uses these nested narratives, each story, you know, getting way to the next, with each, well, like one person's flashback leading to that story where another person, that another person told them and so on. And then begins to snap back into our subjective present. And the threads of a bunch of those stories begin to come together. (sighs) And each of the stories, well, they take you into what the national called, the un-magnificent lives of adults, if you're a middle-aged man like me and listen to Dad Rock like that. The events, the stories are, for the most part, kind of seemingly mundane, but they're also filled with these turning points that seem to guide our lives more than the major decisions that we make do, if you get me. I'm being vague and I don't wanna go into descriptions of the characters and the storylines that ensue. I want you to pick up Blurry, I want you to read it, I want it to unfold for you the way it did for me. There's a whole array of characters and the way Dash brings it all together, it is a remarkable book. I'll say one of the strange attractions of it all is that virtually every page is a two-by-two grid of identical-sized panels and that regularity is sort of hypnotic. You can't do anything with pacing that involves changing panel shapes. Everything has to fit into that geometry. But the drawings, the storytelling, it all works and again, it's sort of hypnotic. You find yourself being drawn in and complimenting that or Dash's clear line artwork and the washes that he uses for tones. And he brings us these epiphanies and frustrations in these characters' lives and some kind of amazing comic book graphic effects to go along with the sort of conversational style of the whole book. And I'm just awed in terms of how he made it all work. And as we discuss in the conversation that two-by-two structure, well, it enabled him to take a more plastic approach to storytelling, we'll get into that. Blurry is just an amazing graphic novel, almost impossible to put down, even as a near 500-page hardcover. Go get it, it's really good. Blurry by Dash Shaw, it's from New York Review Books Comics. Now as caveats go, we recorded at a friend's place in New York City, his computer didn't have the sound offs. There's a lot of pinging going on in the background, which is in coming messages. It sounds like we're in a hotel elevator at some point. I'm sorry, also there was construction noise and motorcycles and things like that nearby. Oh, and the two book comics that Dash talks about at the very end of the show are Firebugs by Nino Bulling and Vera Bushwack by Sig Berwash. And the biggest caveat is I was not at my best for this episode. We had a mid-afternoon weekday recording session, and I think I was just too caught between my work self and my pod self. They are different personae. There's still a big Gil show that goes on throughout, but I was in a wrong frame of mind, and you're gonna hear that. I apologize, I apologize to you guys. I apologize to Dash for just not having my A-game, especially to talk about a book that is just so amazing. So I apologize. Here's Dash's bio. Dash Shaw is the author of several graphic novels, including Bottomless Belly Button and Discipline, published by New York Review Comics in 2021, and named one of the best graphic novels of that year by the New York Times. He has written and directed two animated feature films, the most recent of which, Crypto Zoo, won the Sundance Film Festival's Next Innovator Prize, and was nominated for the John Cassavetti's Award at the Independent Spirit Awards. He lives in Richmond, Virginia. And now, the 2024 Virtual Memories Conversation with Dash Shaw. (upbeat music) So where did blurry begin? - Oh, we're gonna dive right into it. - And we may as well. Well, I had done a short story that was in an issue of phantographic anthology now, issue number two, where a character kind of tells a story inside of a story. I'd done that a couple of times. And I liked that because then we see how the first person reacts to the story. And now, it's someone who moves to New Mexico, and they don't want to buy a car. They want to just buy their bicycle everywhere. But in this town, you'd seem very strange if you didn't own a car. So, and he wants to meet a girl online. But if someone finds out that he doesn't have a car, they don't want to go out with him. So he kind of concocts the scheme to not reveal that he doesn't have a car by meeting him like a particular location. And then at some point in the story, she says, "Oh, I haven't been honest with you. "Like, I don't have a driver's license "because of this incident." And she can't drive. And so it goes into her story. So I had that kind of ruminating. And then I was also thinking about very microscopic moments of doubt between two very similar things. Like you go to the grocery store and you have to choose between two different kinds of beans or two different brands of the same kind of bean. And there's that moment and there's all these kind of different versions of doubt. So I kind of arrived at the first man who his brother's getting married and texts him what to wear to the wedding. And he goes to a store and he has to choose between two very similar dress shirts. And it's part of, I mean, I could laugh about it for a long time, you might bring more out, but the choosing between two very similar things and a story inside of a story, I think we're the first couple of seeds, but then it kind of, you work on these forever and they kind of combine different ideas into one thing. - You wanted to realize it was evolving. - You're not, with your first comic being like 800 pages, I'm used to you going along, but when was the realization that this was a significant book? - Well, that bottomless book wasn't my first book, it was just the first one I met people. - Yeah, people cared about. I like a decompressed storytelling style. I feel like that readers like it, manga is extremely popular. So I feel like this is the pace of the sense of control time that I enjoy. And bottomless, I didn't do any page numbers in it to kind of encourage people just to keep moving through it. And in this one, there's no chapter breaks. So ideally, blurry you read in one or two settings and that's part of the trip of it is that you go into all of these people and then you exit all of the people. And so the length, the number of pages is kind of part of the reading experience that I enjoy, like, I love drifting classroom and that's like hundreds of pages of kids running and screaming and there's a section and kind of the very middle of drifting classroom where it's like a puddle on a ground and it's just a few pages of this puddle spreading. And it's just people have different kinds of ways of controlling time and I kind of like this one. - Yeah, it was one of those in reading it. It was that exact vibe. I was like trying to find a point to put it down. I'm not really, okay, the person telling the story has changed. This is, you know, the point which I'll finally rest my hands for a little bit, come back and read the second half of it. But were there moments of, I don't want to say giving stories enough, enough length or where stories started to grow beyond the scope of what you thought they were going to be. You know, with that nested structure that you use throughout of story, within story, within story. - Well, because every panel is the same, this is sort of a technical answer. - Yeah, that's what it is also. - You have a two by two grid for the entire book. - So I just thought about the panel, I just thought about what was happening in the panels, not page, I didn't want to do any weird page layouts. I just wanted to be in the panels. And so that also meant that I could add things and move things around. And so when something felt too long or too short or I could add, I could very easily edit and construct it. So that was also, I couldn't serialize the book because I was kind of drawing things in the first half to match things that I discovered in the second half. I was going to ask that the art grows tighter. The art grows fuller and more detailed, it seems in the second half. And I wondered, now I, that feels more like something where you were looking back and forth through it. So-- - Well, a lot of the last things I drew were in the first half to, so-- - To say the riff, I don't know. You know, I'm certainly not the most consistent artist with my hand. - The characters look distinct. They all look like who they're supposed to look like. - That's the most important thing, yeah. - To me, that's number one. But tell me about working in that two by two that you set up for this, which again, I now get, is also working in terms of literally the mechanics of making the book. Compared to the last book we talked about, discipline, where things were floating. There were pages it felt, at least, as opposed to-- - Well, that one, you know, I'm sure other guests have talked about the Chester Brown method of drawing each panel separately. - Yeah. - And for discipline, I drew each element separately. So the text floats, everything floats, and that was inspired by civil war era illustration that doesn't have panel borders that I probably talked about when I was last year. But so there's kind of a quietness. And it just meant that I could, if I felt like drawing trees that day, I would just draw a bunch of trees and I could kind of collage the pages together. So it was even more malleable. Also because there aren't word balloons, I would find pieces of text from actual diary entries to stick in to the pages. So everything was very, very malleable. But it was, that book took a very long time and I did this book asked for something different, a different way of editing. So they look different, but they both came out of different ways of being able to make changes and adjustments to the whole story. - That's a problem with a lot of comics is that they're serialized and then when they're collected, they don't make any sense. The first half is bad and they didn't know what they were doing and they kind of, it got better as it went. - And you reversed it. - I'm trying to make something that is good from beginnings and that it involves a different approach for me. - Did you have this in your head while you're working on discipline or was it a, I just need some time and a different mode. I need to get away from how I was working before. - I started it in the middle. I quit discipline a bunch of times. I thought it was a bad idea for a bunch of different reasons. So somewhere in the middle of that I focused on this and so many things happened. There are projects that take a long time and I think that I'm sure the doubt of working on discipline somehow rolled into this because I was filled with self-doubt on that book and kind of questioning every little aspect of the book. And also making movies is like that too where there's lots of micro-decisions that you can fixate on that don't necessarily, they probably don't change the audience's experience that much but you can still go back and forth on whether you should use take three or take four of one scene. And I'll bolt up a wake at night four years later thinking why did I choose take three? - Which plays into blurry at one point. There was a, not a meat cute, but a meat rage, I guess, where characters are arguing over a conduct. - Oh yeah, a scene in a documentary. - Yeah. - And it's a, you know, I've been to those-- - Test screenings. - Test screenings for documentaries. They're especially interesting because you see just how much they're changing, what people will perceive as being true. And someone's whole life can be cut out of a documentary and they feel like they weren't part of an important story or something just to keep the pace of-- - I have a whole-- - A whole comics thing to share with you about that. - Okay. - But we're off Mike at some point. But hold on, I'll tell you that part later. - So the, yeah, the doubt of discipline and yeah, the films, different things going on while working on this. - You know, I did Clue in 2019, a comic mini series that IDW was my mainstream monthly comic mini series. And I think that that helped me with everything because I had to make something very quickly. I did it on a monthly deadline. - Yeah. - So it'd be like, I need Scarlet's story, you know, and I just pull it out of my ass, that bit, because I had to have it done. And that helped me to kind of realize, well, there's a lot, you know, you can get a lot done if you just force yourself to do it and not get stuck. - I had wondered if the two by two grid was part of that, giving yourself parameters. But it seems like there was more going on for you in terms of using that structure. - I did pick up some drawing things from doing Clue. Like for, you know, there were a lot of like game board kind of image game board designs and Clue. And so that kind of led me to use more circle and square templates for word balloons. And I kind of use some things from Clue in this. - How do you feel your arts, I will say progressing, changing, you know, other aspects of blurry you couldn't have done when you were starting out or even a few years into your career? - That's a really good question. Because thematically it feels like the book of somebody who is, well, say middle aged, not that I want to project exactly, but somebody who's looking at turning points and what middle age means. But again, I am projecting mobile, put it in those terms. But it does feel like a more mature book in certain ways. And I don't know if there's aspects of storytelling, art making, et cetera, that you don't feel, that you feel you grew into. - Wow. - Or is that something for the critics to talk about? - Yeah, I don't know, I have to, I wonder what the, I'm wondering what the first thing that would pop into my head would be. I was at, you know, I always liked comics. I never went out of a period of not wanting to do comics. So I've been doing comics since I could draw. I'm very, very young. So they, you know, the comics I drew when I was 10 or were different than the comics that I drew when I was 20 and different when I was 30. And so I try, I don't. - From the inside, it can be very tough to see. - I guess I would just try not to think about it. That's not really true. I just don't even know what kind of thoughts I would have about it. I would just be, and I also have a bad memory. And so now sometimes I'll remember the book I did about something as opposed to the thing. - Yeah. The making. - We didn't actually talk about your comics upbringing when we talked in 2021. You know, where did comics, you mentioned drawing at 10, but when did comics start for you? And how did it, you know, how did you grow into comics, I guess? - Yeah. The, I've said, I did, I talked about this so much that I, maybe I didn't bring up 'cause I grew up in a very comics friendly household. My dad read comics, they were around, you know, he liked the spirit. They were like the print in my childhood home, the prints on the wall where there was like a Will Eisner print. What's his name? Edward Gory, Edward Gory was huge. You know, he was like, he was very hip to, he had fantastic planet on a VHS that I saw very, very early as a kid. And he, he collected, he knew kind of exploitation movies. And so I didn't, a lot of cartoons had an older sibling, but I had a dad. And I think, you know, something that I've later kind of thought about is that cartooning peers of mine, I think comics was associated with something that their parents didn't like. And so it had a bit of a titillating rebellion quality or that the, you know, the imagery of this horror comic was, and, and, you know, I think Ben Mara does a great job of kind of providing that to a reader and making objects that feel like they should be hidden. But, you know, if your dad is into him, they aren't so transgressive, you know. So I didn't, and he was into pretty, you know, weird, violent stuff. And so the, the comics that I, that were, my dad never got into the Japanese comics. And I was the right age when all of the, the Japanese comics were exploding. But he would, you know, he would drive me to Otakan and drop me off, I think, and go to anime conventions. - Yeah, that's usually a question of what do your folks think of you going into comics. That's what I, I asked people, it sounds like they were, your dad would at least have been understanding. - Yeah, and my mom was a play therapist, which I feel like is some part of this too. - Yeah. - So as blurry was evolving, how do you, how do you keep track of what you're doing? You know, when it comes to, to organizing the whole, let's say Matsrosuka, Russian doll, you know, structure of it all. You know, was there a degree of, I've got to stick the landing on this. And I think I know where it all finishes, but, you know, trying to make each one of those stories substantial in and of itself, as opposed to just a contributor to something that comes later. - Well, how much of a challenge was storytelling throughout this book? I guess is a shorter way of booking. - You know, again, because I could move things around, it, it's, it was a process of discovery and getting things into alignment. And I wanted, I wanted it to feel a, have that feeling that it's rambling and you don't know where it's going to go. And you're like, what, we're following this other person now. Oh, the person's still choosing between the ice cream flavors and flipping them in. But ideally around the middle point when it starts bending back. So, so it feels like a run on, like automatic writing, basically. And then I hope it feels fun when it starts bending back in the latter half. And then you're like, oh, this is all about this. This was all about this. And so that the latter half would be enjoyable because you're, I'm delivering on something that started off rambling is kind of looping back into a feeling of synchronicity or a rhyme. There's usually, there's rhymes between the first and the second half of people's stories. And I think that comics, honestly, is if I do my job and I draw the characters differently enough, which was a big part of it and making sure that they are, they each do have their own thing going on, then it's not confusing. So some of the last things I did in the book were just putting patterns on people's shirts so that you could track them and trying to put a detail in a location so that you don't get confused, but not too much detail, you know, kind of, so that's still legible and yeah. In terms of just finding the visual mode, sticking with that sort of clear line, getting away from the hatching of the dominated discipline and going with washes and an easier line style. - I did, again, it kind of grew out of the story. And so I do think that for whatever my hand can do, not that I'm definitely not a fantastic chameleon, but I'm trying to draw in a way that's appropriate to the story. And so I thought that drawing in this pared down way with the characters would make it legible. And I had maybe somewhere around the beginning of this, I started to get more into the New Yorker gag cartoonist kind of guys. And especially, you know, Garrett Price, lots of people love white boy, but he did a bunch of gag comics. And they're not even particular, they're not that funny. He wasn't a very funny gag writer, but he was a great artist of humans in mundane places. And a bunch of them were collected into a book called Drawing Room Only that you can get on eBay for 20 cents. So the non white boy stuff by Garrett Price and also the washes by Abner Dean, I really loved. I think the washes also helped the clarification of all of tracking everything. And then something I figured out with bottomless belly button is if you spend years drawing a book, it's good to coat it all in one color. It kind of helps disguise the idiosyncrasies and the drawings. So, you know, I did a very, very dark blue ink for everything. And that was also a bit inspired by a great book that I should say Joe Kessler, who co-designed the cover of this book with me and helped a lot on the production on blurry. I always really loved his breakdown press designs and he did a book called Fukushima Devil Fish that is in a dark blue ink that I referenced a lot when we were working on blurry. - You don't have to answer, answer, but tell me about working with New York Review Comics. I'm so used to the Fanta and drawing quarterly guys. I love sitting down with New York Review books as they send me all the great comics that they're doing, both the reprints and some of the new stuff. But what's your experience been like with a different sort of publisher than we're in? - Well, I like it that they only put out a few books in a year. You know, I'm not, my mental health cannot take what is probably required of me hyping myself up constantly on the internet. I have a hard time. I do the best I can't. I do what my personality, I can do what my personality allows. I'm at the edge of my personality on that. So this book, it came out a year after it could have come out 'cause I have to fit onto their slate. But that also kind of helps me because I have to be patient and not think about participating in the world. I just have to work on the book and the books come out whenever. They gave me lots of notes, which I also like. When I was younger, I didn't have this attitude, but being through some film screenings, you find you, you can, I just wanna know the notes so that when it comes out, I have hammered it through. I've done lots of books that have spelling errors and factual errors, I've done it. I don't, I'm ready to not do it anymore. I wanna get the paper, I want the proofs back from, I wanna approve the proofs from the printer. There's always some tiny little thing that has to be changed, you know. If so, they do all of these slow-born things that I really appreciate. So, yeah, I wanna do all of the boring stuff. - Yeah. So when we talked in '21, your movie had come out a few months before the book that we were doing. Discipline. Now that the movies had a couple of years, and you're in New York because there was a screening last night, I think. How's the film experience comparing to the comics experience for you in terms of longevity, storytelling? What are you taking from, you know, seeing the afterlife of a movie like this? - The afterlife of it. Well. - How different is it, I guess, than, you know, putting a book out or, tell me your impressions, whatever's going on in your head about, you know. - They're very, very different. You know, at this point the movies have grown and so they're not as large as other people's movies in terms of their scale, but they're now social, my social projects, meaning they involve other people. And my books are my anti-social projects, you know. - In terms of collaboration with everybody else in the movie, you mean? - Yeah, you know, so like I can wake up and I can work on my comic and it's just me and my space and I can generate things. I don't need to explain to people what I'm doing. And then after lunch, I'll work on film stuff, which is usually explaining to other people what I'm doing. Or asking artists to contribute in just making adjustments and we have our little team in Richmond, Virginia, working on the next one. So, and about it having come out. I mean, their very books are internal and I like that and they're silent and I like that. And we did tons of drive, you know, drive-in screenings for crypto zoo because it came out during COVID and Sundance set all this stuff up and it played, I've got to travel the world and see all the animation festivals and all the funky things. And I've gotten to, the animated movies have allowed me to have all of these other kinds of experiences. Comics also has taken me places, but. - They're definitely ecosystems. - They're definitely in different ecosystems. - Yeah. - How much of an overlap is it? Do you find people who've seen crypto zoo who have no idea that you're making books too? - I don't know. I mean, I've found that less crossover than someone would think. - Yes, I wondered whether there's. - No, they're different. - It's own distinct audience. - That's what it seems like. - Yeah. - Yeah. And my movies are definitely like independent film audience, you know, and they play well at film festivals because that's where people want to see a weird animated movie. And then, you know, when they have the theatrical release, they, it just sort of confuses people. And the, no, I don't, I think some people, I, you know, I just don't, I don't know. It definitely seems like a different. - Yeah, it was a very few people crossover in my mind. - I wasn't sure if you'd meet people who, oh, I saw your movie. And then I realized you were this cartoonist and, - It's happened a little bit, but also the books are quite different from each other. So if I had a, if I had a game plan to acquire fans and build my empire, I would have done things a lot differently. You know, I think there's, there's, being consistent is great for that. And I would be happy to be consistent. It just hasn't turned out that way. So I spend more time thinking about just how to make money to be able to afford to keep going than other things. - You're happy with blurry. And, and, you know, the final, final version of time. - Totally. Yeah. Very, very happy with it. It really felt on, that it felt like I had played a video game for very, very long. And I had gotten, I found a bonus level or something. - Yeah. - You know, and that was very exciting. - I'll say one of the interesting things to me, given what I do with this whole sitting now with two microphones and somebody else vibe. A number of the stories that emanate in the book begin because somebody asks somebody a question. It's less of a, let me tell you about the time this happened and more, why did you end up doing this? Well, you know, then, then stories start to unfold. That conversational sense, I guess, that, that sense of dialogue, how much, how much of that was coming into your, your comics writing versus, you know, writing for a film or where to dialogue begin for you. And, you know, that sense of two people can actually, something can emerge from two people that isn't necessarily, you know, as good as an dialogue. - Yeah. - Well, the, man, that's hard to ask. - I know, it's a weird one to ask, but you know, how stories come out of two people interacting. - Well, I had done, I don't know if this really answers your question, but it's just sort of popped into my head. But somewhere around bottomless and body world and these different kind of comics I was doing, I realized that naturalist, I thought naturalistic dialogue is just another form of stylization. That's something that sounds real. There are, nothing is real on the comics page. And so there are kinds of things that you can do that sound like it is real. I don't know if that's helpful, but because I tried things with, you know, with the book New School, the dialogue is kind of based on or inspired by very, like almost like Jack Kirby kind of comics where people are speaking with exclamation endings. And then discipline, obviously, that's found language. - So when it came to blurry, I was like, I want it to feel like you're hearing something and you don't know what is important. Part of quote unquote realistic dialogue is that you don't know what is important in it. People will kind of meander to get to their point. So that has to be a very deliberate decision, obviously, of course, in a comic because you have to go read or work. You have to guide the reader pick all, find the spacing of the word balloons and really hammer it out. So you have to kind of go out of your way to be a bit more loquacious than you would be if you were doing a play or a podcast. At least that's how it seemed to me. I don't know. Is that kind of answer? - Yeah, it's in a sense. It's one of those. To me, it's just the charming aspect of it, in a sense, I hate charming as a term, but we'll run with it. - It is the sense that it's the thing that emerges between people, that it's not some person, just sitting there, staring at a wall and having a reverie and going into a big memory. So much of it is what comes from talking to someone else. - Yeah, someone who read this said that it felt like, especially after COVID, my book felt, he said my book felt like being in a crowd of people again. I thought that was great. - Yeah, that's very much a great way to describe it. - Yeah, 'cause it is broing in on this one moment, but it's moving through a lot of people in a, I hope, exciting way. - Now, you bring up doubt and that, you know, the decision between two almost imperceptible and perceptively different things, but turning points are a big aspect. Some people are making momentous decisions in the course of the book. This is the middle age guy, I think, again, that sense of turning points, that sense of those decisions that you know are irrevocable. You deepen that world at this point or you're still in the, "I'm saving a lot of possibilities for myself." Tell me about turning points in your life in the, you know, real key in or whatever sense, right? - The only, the only thing I feel like I'm gonna, well, I think part of the style of the book is that someone will make a choice, but it will have, it won't arrive at the, one-to-one conclusion as the stories ripple out. So I tried to have it be more fluid than, because, like, for example, and again, that's a form of stylization, I guess. Like, you know, the case on the character in the story, he's in these drawing classes and he says, but he was like, he says I was a sculpture major, but for some reason I took a bunch of drawing classes. And I feel like that is part of the style of the book. Humans know that you don't necessarily major in what you end up being interested in. You find some other class that you end up being involved in that's outside your major, especially in art school. So he made a choice, but he kind of arrived at something that was only adjacent to the choice. And a lot of the characters in the book will do that. They'll be like, well, they choose this one thing, but it ends up resulting in this thing because of whatever activity they had to do to arrive at that choice. So the... - The externalities can get to us too. That's not just the individual choices, but the life that, you know, comes out of nowhere at you. I mean, my joke is I'm a lobbyist for the pharmaceutical industry, but I have no science background or pharmaceutical experience or regulatory or government affairs or anything like that. I just kind of ended up in this job, which is part of why I do this by evening, so I can stay sane. But yeah, we end up in lives we didn't exactly plan or we make decisions that don't seem momentous, but the rest of life has other plans for us. - Oh, again, projecting the middle-aged guy thing. - I know I'm in the middle-aged. I don't, you're an artist, I admire the, you know, I'm the old man in the room, it's okay. But, you know, I thought of something when you mentioned Garrett Price earlier, have you ever had that New Yorker vibe or the gag panel bug? - You know what's funny is for a while, Jane, who is now my wife, she was an assistant to a New Yorker cartoonist and so she would be invited to some of the New Yorker gag cartoonist parties and I would go. And it was a very, a lot of them at that time, I don't, you know, they were kind of like stand-up comedian-type people that got into drawing comics. - I've been told, years ago I was told I needed to come to the Chinese restaurant where they all met. I was like, you know, I'm not sitting in a room with a bunch of gag cartoonists at that. - They're very funny people. And when I first moved to New York, the cartooning scene was so different because they were people that were doing things for the alt-weekly's. - Sure. - So they were funny people and they were kind of odd characters themselves. I mean, I know that the cartoonist, everyone's an odd person when you get to know them, but I lucked out 'cause kind of the, the, I wanted, even in college, I kind of wanted to do things like what I'm doing now. - Yeah. - It changed a bit, but the, yeah, I don't know, I've never, I've-- - Just never had that, that. I think of guys like Carl Stevens and Everett Glenn and people who panel to panel strip guys who also found, you know, that they could do gag comics, or gag panels for the magazine. - The gag comic is hard, I, yeah, I don't know. - And one of my first ones, I mean, we have a Ross Chas card in front of me, but Ross connected me with Sam Gross many, many years ago, the late Sam Gross, and just sitting now with somebody who was operating at that level for like 50 plus years, I'm like, that's a different mindset completely, that's, you know. - Well, tell me, you said you had a different idea what you wanted to do in comics when you were in college. - Oh, I'm, I just, I didn't have, I, I think, again, kind of like you're saying you played the, yeah, I was a little surprised that to arrive at this, because I don't really think that if you had asked me, well, what kind of comics you would do at my age now, we would be blurry, I don't know. I would have been happy, I still honestly, like the clue, doing clue helped me because still somehow in the back of my head, comics are monthly. - The pamphlets that were genre stories. And clue was good because I can draw in a way that I feel like is appropriate to clue. I don't think I could draw in a way that's very appropriate to, to a lot of the comics out there. I don't know, it's a bit of a, it'd be a bit of a stretch, but I don't know. - But like history with how it, how it turned out. - It was a college self-thinking Spider-Man or, you know, the whole superhero world where we were already kind of indie by the time. - Definitely indie, you know. My dream at, my dream at 16 was to be published by fanographics and, you know, that was it. - And I think of those, like what you're describing with clue reminds me of Roger Langridge, one of my all-time faves and a past guest who when Boom announced that he was going to be the cartoonist for the Muppet Show, I thought there is no more perfect combination out there of, you know, IP and a guy who perfectly, perfectly captured not just the visuals, but, you know, the whole vibe, the vaudeville thing. So those rare instances where, you know, that sort of stuff does make absolutely perfect sense and leads to really great comics. But yeah, the indie versus, you know, we'll say big two or big three or whatever it is, that whole publishing vibe where it's more of an assembly line has got to be a choice you made very young, I guess. - I would have been happy to do anything. - Sure, sure. - Yeah. - They had hired me, sure. - Are there other storytelling genres you're looking at or interested in or, you know, man, I would love to do a story about, or is that jinxing everything when it comes to-- - Yeah, I don't want to-- - No, don't do that. - But I got things cooking. - Yeah, you mentioned finishing the book over a year ago. - Um, no, I mean, it's going to come out like that, yeah, I think. - Yeah, just been working on something since. - Yeah. - Okay, you're not going to talk about it the slightest, right? - I don't think I should. - No, 'cause I am going to-- - I'll change it, it'll look bad and-- - Yeah, I found that early on in the show, people would talk about the project they were working on next and I'd revisit them four or five years later, nothing to do with whatever, just kind of, absolutely nothing to do with what they were talking about in, you know, 2015 or '16. But talk about the animation. Talk about working on, what have you learned from the previous projects that feeds into how you're working on a new one? Without, again, going into what you're working on exactly, are there aspects that you've, are you getting better, I guess, at working on these things that more management than story or? - Well, I can say that the main character in the new one is voiced by a kid, a 10-year-old kid. She's in pretty much every frame of the movie. And I was kind of inspired by the John and Faith Hubley animations and particularly the voice acting and that. When I had done high school syncing, I originally thought I didn't think I would get known actors in it, so I tried to write something where it'd be voiced by kids, so the thought would do. But I changed, you know, I changed, and that's not how that one turned out, but I still thought that there was something, especially in those Hubley cartoons with that particular voice acting, that's extremely powerful. It feels like a documentary voice being paired with a very artificial world. So we got a casting director to find the kid, and we found her, she lives outside Philadelphia, and it was a whole journey. We had to audition tons of kids, and it was so cool, and we recorded her, and we kind of are constructing the movie around her perspective, and she's... 'Cause I always, of course I love the Miyazaki movies, but part of my problem with them was that I always felt like the kid was too kind of milk toast in the center of it. I thought it should seem like a kid who might actually be crazy, you know? So we found one, how to deal with it. I tell people that she's my class kensky. (laughing) - That's, did you know that was what you were looking for, coming out of your last couple of projects? Or is it a, I don't know what the process is for-- - Each one has been different. I mean, this story asked for that, and yeah, you kind of put things together, and I think that's something that's similar with everything that I do is they're basically collages. - That's gonna ask. - Even movies. - Do you feel you're building towards something, or do you feel things develop organically, I guess? That's, what I'm wondering. (laughing) - Building the work, anything. - Or is that the collage split between those two? - Well, the kind of art that I like is collage, art, you know, like Renee Magritte. Max Ernst said Magritte is collages painted entirely by hand. And when he, and I, when I read that quote, it's like a light bulb went off in my head, it made sense to me. Because he by executing them in a similar way, meaning there's a surface sheen over something that is a collage, like an apple in front of a face, right? It's the famous one. But there, all that's to say that you're kind of pairing things together to equal third surprising things. A plus B equals, holy shit, Z, whatever you know. So whether that's pairing a particular score with an image or sometimes with the movies, they're elements painted drawn by different people that you're trying to bring in alignment and you're kind of hoping that, you know, there's, I like it when the difference, there's something poetic about the differences of things being as heightened as their similarities. So, and comics obviously are kind of, I've said it a bit a million times, but they're collages that have kind of rules that you begin at the upper left hand corner and you end at the lower right. And there's an accepted way of reading a collage. About it, I definitely don't have the whole, they are organically arrived at and I try to be open to intuition or mistakes. - Do you think of working in live action or? - No, it would seem that animation would be, not just because of your drawing, but the, again, the collage, the ability to put it together after the fact instead of having to have everything in place for the actors. - When I, you know, the first, even when I was in college, I liked, I always, in high school, I liked a zone of animation that was related to comics that's like limited animation, like the Charlie Brown Christmas special and Speed Racer and Akira was, you know, made by a cartoonist based on his comic and I liked that mode. It made a lot of sense to me and it related to independent cinema, kind of like less is more mode. So that was, it was never a dream to work at Pixar, Cartoon Network or the direct live action and it was always the other thing. And then I was so lucky that very early in my early to mid 20s, I did a series for IFC channel, Don Club Man, that ran between movies on the IFC channel. And so that was some outside force saying, "You, you, you're onto something." There is a connection between what you're doing in independent cinema. And from there, I went to the Sundance Labs and that was like 2010-ish and that was when I was kind of deep into trying to make these things. So I've only made a couple, but that's still, you know, not many people are making independent animated movies and more than a lot of people. And they've each taken a long time. So in the third one, when it comes out, it'll be approximately five years between cryptozoos, so they each will have taken about five years to make. And I wish I could, I kind of, I would like to get it down to four years. Yeah, that's good. - I was gonna ask whether there's any, not efficiencies, but just things you realize, like, - If I had really quite a dancing, if I had like, if they were making more money, then certainly everything would be, I would, everything would be different around them. But the, but also, you know, and I, people laugh when I say this, but I don't think people actually want one of my movies every other year. Like the, you know, that they're pretty their own. - Yeah, they're, I think if it's an event for a year, you know, it's okay, there's, there's. - Some people didn't want a Star Wars movie every year as it turned out, so, you know, they thought they were mining something and realized audiences, they like to wait. They like to, you know, admittedly with you. Yeah, four years would be better than five, but, but, you know, I understand. It was a weird question, but, you know, given that we talked in 21, I think we were in the vaccine era, but not traveling at that point. What was the COVID era and beyond for you in terms of? - My pandemic was that lots of people around me died and it was horrible. - Yeah. Yeah, it's been interesting to see how people talk about, cartoonists talk about it. 'Cause to me, it was about death. - Yeah, most of them didn't have losses like this. I'm so sorry for bringing it up like that. - No, it's okay. - But yeah, it's okay. - It seems, we remember like being in New York, I'm in New Jersey, but, you know, for us, it was the, because this was one of the epicenters early, it was that sense of like the cooler trucks and everything else sitting outside of my friends in New York would have all these horror stories of the ambulances at all hours, but, you know, what it meant, you know, I guess in the aftermath, you know, beyond what the coverage was, I guess. I'm cutting you off. I apologize. I don't know if it's something you wanna... - No, I think, and I had a, you know, I had a little girl to do it. So you had to tell like your little four-year-old girl not to go near other kids on the playground. And I thought it was terrible. - Yeah. You mentioned how blurry, how a reader felt blurry was not an antidote, but that sense of overcoming social distancing. Do you think that was playing into it as you were making the book? - Well... - Or do you not think of those as motivations? - I was also, I don't, you know, it's... - It's sort of difficult. - I've only thought about it. I'd only kind of thought about it after, but the, I started discipline. I thought, when I started discipline and crypto zoo, Obama was president, and I thought Hillary Clinton was gonna be the next president, you know? It was a different kind of vibe. And definitely living in Richmond during... Some people might think that it made me want to work on this Quakers of War thing when all the monuments were going down and all of that, all this stuff. But, and it did feel, of course, that the city was addressing something that had been unaddressed for many, many years. But the truth is, I didn't, I was not anxious to be at the drawing board on a downer of a, it was not fun to work on, you know? I did not find it inspiring. It was just a bummer. So, I think, "Blurry," part of the mission with "Blurry," is that, this sounds a little funny, but the idea is that there's nothing that's too funny, and there's nothing that's too dramatic, that I was aiming for a mode, almost like an ambient album, where it's like you are in, you're in the zone, and there's something kind of pleasing about it, but you, there's very few actual jokes, and there's very few actual dramatic things happening throughout the book. You're just plugged in and you're in it. And I think that it helped, that that was a healthy thing to work on. And it must have been, 'cause like, you know, I kind of was working on it when I didn't want, when I had decided that the other projects were not where that I should abandon them. - Yeah, I get you. I don't want to say it's a comics as therapy vibe, but there is a degree of storytelling, at least in different modes. - I've definitely figured out that, you know, my mind is best when it's on the drawing board, drawing board, and when, you know, it'll go. - Go, yeah. - It goes on the page, as opposed to staying stuck in your head. - That, and just the, I'll crash hard if I use, usually, if I'm feeling down, I'll realize, oh, this actually has to do with the fact that I haven't drawn for a while, and instead I've been doing this other thing, yeah. - So hit you with the question, I probably hit you with last time, but I don't know if you're prepared for it. What have you been reading? - What have I been reading? - Comics, prose, poems, whatever. - I have to, do you bring anything with you for the trip? - Or is there something you've read recently that just knocked your socks off that you had to force off on other people? - Oh, I have a good comic that I read. - Yeah. - I really liked fire bugs. - Don't know who's about it. - That drawn and quarterly put out. I don't remember the artist's name. - Oh, look at it. - Yeah, I think it's the first book that I've read, and it kind of, it kind of the drawings are spectacular. It kind of feels almost like a Sayichi Hayashi comic. And yeah, drawing and quarterly put it out. I think some other publisher originally did a visor graphic edition, but I just got, I also liked another D&Q book that I thought was much kind of, it was very different than what the cover suggested, which it was like Vera Bushwack, you know, that one. - No, no, no, no. I think I'm saying the title, right? - I'll correct it after if we have to. - Those two were great. Other comics. Yeah, well, there's two. - I'm willing to take that. That's, you know, I'm always looking for recommendations and the next thing to read. The problem is everything that pops into my head, I'm like, oh, I didn't actually didn't like that one. - Yeah, that's always a thing for me is the, let's just pretend that's, that's. - Don't wanna say that one thing. - It's okay, we'll leave off with these ones. But Dash, thanks so much for, I'm glad we're get to do this in person instead of just doing a remote like last time. And I'm glad you came up for a screening in New York, but thank you so much for sitting down and for just, for putting in everything that goes into blurry. - Oh, thanks. I know you say there's, you know, no drama, no laughs, or at least it's my, there's a lot in this book. I got a lot from reading this book. - Oh yeah, I didn't mean, I didn't mean - Not even knocking it, knocking it. - I meant that the, yeah, there's, it's more kind of like a zone, a zone of a mode. - And that's right on my alley. Maybe for just where I am right now, but this is a wonderful book for me. - Thanks. - Thanks so much. - Did you ever read any of the Natalia Ginsburg books? - No, no, I know they're, again, New York Review stuff. - Yeah, they did, but other publishers have put her out and they have a kind of story style where it's hopping around in different, it's kind of about other people and it's dipping into other people's lives in an interesting way. It's different than my book, but the, I recommend those. - Always looking for more. Dash, thanks so much for coming. - Thank you. (upbeat music) - And that was Dash Shaw. Go get blurry from New York Review Comics. It's an absolutely and deceptively fantastic graphic novel. I've told you enough about it and you got a, some of that vibe from the, the conversation itself. And go check out Dash's other books and his animated films. It's all at his website, dash Shaw.net. That's D-A-S-H-S-H-A-W.net. I gotta go check out that clue comic book that he did 'cause it sounds a lot different than what I'm used to from Dash and something I'd love to see. You should also check out our Watch Crypto Zoo, the animated film we talked about. I bought that on Apple TV so I could stream it whenever back in 2021. I'm not sure where or if it's streaming free, but you can go buy it. Either DVD or Blu-ray or buy a streaming version. Do yourself a favor, check that one out. Now Dash is on Instagram at Dash_Shaw. But as he mentioned, chasing the social media thing is not great for him. But he does post excerpts from these books and other projects there. So it is worth checking out. Now, you can support the virtual memories show by telling other people about it. Just let them know there's this podcast comes out every week with really interesting conversations with fascinating creative people. You can also help out the show by telling me what you like and don't like about it or who you'd like to hear me record with or what movie or TV show or book or piece of music or theater or art exhibition or whatever. You think I should check out and turn listeners onto. You can do that by sending me an email, postcard or letter. I put my mailing address at the bottom of the newsletter. I send out twice a week. Or by leaving a message on my Google Voice number. That's 973-869-9659. That goes directly to voicemail so you don't have to worry about getting stuck in an awkward conversation with me. And messages can be up to three minutes long. So go longer than that, you'll get cut off. Just call back and leave another message. And let me know if it'd be okay to include your message in an upcoming episode of the show because you might have something interesting to share with listeners, but I'd never run something like that without the speaker's permission. Now, if you got money to spare, don't give it to me. I mean, sure, I spend money on tolls and gas and parking and all that stuff to do these. But my day job treats me pretty well. And I am gonna ask you guys to help fund the book that I'm making at the end of this year. But in the meantime, help people, help institutions. There's a lot you can do for people in need if you go through like go fund me or crowd funder, indie go go, Patreon, Kickstarter, all those things. There are people who need help making medical bills or rent or car payments or veterinary bills or getting an artistic project going. A few dollars might make a difference in their lives. So try and give. With institutions, I give to my local food bank and world central kitchen every month, but there are other things I give occasionally. I make targeted election contributions, but I'm a lobbyist, so that's part of my job. But Planned Parenthood, women's choice, freedom funds, election funds, there are all sorts of things you can do to try to help make a better world. So I hope you will. Our music for this episode is "Fella" by Hal Mayforth, used with permission from the artist. You should visit my archives to check out my episode with Hal from the summer of 2018 and learn more about his art and painting. And you can listen to his music at soundcloud.com/mayforth. And that's M-A-Y, the number four, T-H. And that's it for this week's episode of "The Virtual Memories Show." Thanks so much for listening. We'll be back next week with another great conversation. You can subscribe to "The Virtual Memories Show" and download past episodes at the iTunes Store. You can also find all our episodes and get on our email list at either of our websites, vmspod.com or chimeraupsgira.com/vm. You can also follow "The Virtual Memories Show" on Twitter and Instagram at vmspod at virtualmemoriespodcast.tumbler.com and on YouTube, Spotify and TuneIn.com by searching for virtual memories show. And if you like this podcast, please tell your pals, talk it up on social media and go to iTunes, look up the virtual memories show and leave a rating and maybe a review for us. It all goes to helping us build a bigger audience. You've been listening to "The Virtual Memories Show." I'm your host, Gil Roth. Keep reading, keep making art and keep the conversation going. (upbeat music) (upbeat music) (upbeat music) (upbeat music) [BLANK_AUDIO]