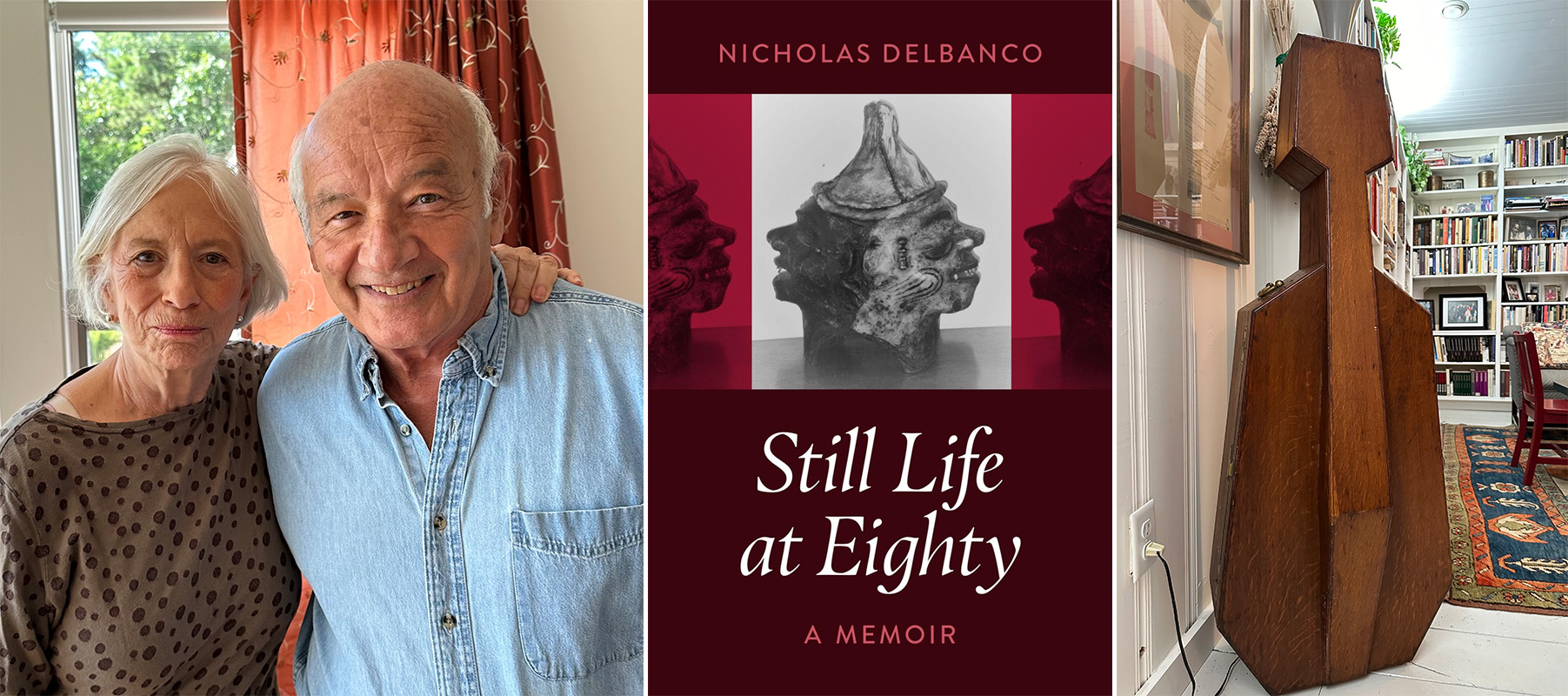

Nicholas Delbanco returns to the show to celebrate his 32nd book and his first true foray into memoir (or ME-moir), STILL LIFE AT EIGHTY (Mandel Vilar Press)! We talk about how the rediscovery of the 40-page history of art he wrote at eleven years old (!) sparked this project, how he built the book as a mosaic, why he centers it around the homes, totem-objects, and writers in his life, and why he wanted his first memoir to be an act of gratitude rather than a list of complaints. We get into decision to part with some of his library and the books he regrets selling, his long-term interest in literary and artistic reputation and how its study helped him navigate the transition from "promising" to "distinguished" writer, his writing practice and process, and what he learned when recently revising a series of his early novels. We also discuss his embrace of compression and restraint in his later writing, why he'll write a fictional character's poetry but doesn't write poetry on his own, what his family's history and business taught him about the balance between the dutifulness and risks of art, his surprise at how quickly John Updike's reputation waned, what he's learned in his 80s, and a a lot more. More info at our site • Catch up on my 2017 and 2022 conversations with Nicholas • Support The Virtual Memories Show via Patreon or Paypal and via our e-newsletter

The Virtual Memories Show

Episode 603 - Nicholas Delbanco

(upbeat music) - Welcome to The Virtual Memories Show. I'm your host, Gil Roth, and we're here to preserve and promote culture one weekly conversation at a time. You can subscribe to The Virtual Memories Show through iTunes, Spotify, YouTube, Google Play, and a whole bunch of other venues. Just visit our sites, chimeraobscura.com/vm or vmspod.com to find more information, along with our RSS feed. And follow the show on Twitter and Instagram @vmspod. Well, I hope you had a decent Labor Day weekend. I did okay for my part, pretended to relax a little, went to a neighbor's kids' baby shower, which, you know, went fine. Made some real progress on the next issue of haiku for business travelers, which I've been dicking around on all summer. The previous one came out like Memorial Day last year, and I thought, "I'm gonna do one a year." And well, I got some stuff done. There's still a couple of major things that need finishing to get that out, but I'm hoping for this fall. Oh, I also read the books for my two guests this Thursday and I didn't have too much anxiety about my upcoming conference and the overall craziness that's looming for my next five or six weeks. I mean, I'll be out of my mind with stress until just about mid-October, right before Yom Kippur. So like October 11th or 12th, things finally stop or so I like to believe. But that's what I signed up for. On the plus side, or I guess the minus side, I retook control of my body in the last few weeks or maybe my mind. I mean, I short-circuited some of my compulsive behavior that had really been racking me. I stopped snacking as a way of channeling that aforementioned anxiety. Then I, in the process, managed to drop 10 pounds in like two weeks. And that actually has my body and I guess my mind feeling a lot better. I was just concerned that I couldn't shed some of the weight I put on this year 'cause I had this neck injury in January and things went on and off since then and kind of derailed a lot of my exercise routines and all this stuff and then the anxiety, blah, blah, blah. And I felt like I was declining. I felt like I was stuck somewhere and every night I'd be pissed off at how I felt and every morning I would tell myself, I will change today and then something did change. I don't know exactly how or why, but I kind of forced it and there we are. I mean, I just figure it's gonna be tougher every year to make corrections. So I'm kind of glad to see that I can still rearrange my brain and my body. I mean, I worry about age in that respect, that inevitable decline, although I am in better shape now than I was like 25 years ago, but ostensibly I'm also wiser than I was back then through experience and contemplation and I really think that the dozen plus years I've spent making this show, just reading and learning from my guests and both what they have to say and what it means to listen to them. It's changed my life and like I say, I think it's imparted some sort of wisdom. I'm not entirely sure, but that does get us to this week's show. See, my guest this time is Nicholas Delbanco, who has a new book out today, Still Life at 80, a memoir from Mando Villar Press. Nicholas has been on the show twice before and with his first foray into memoir, we figured it was time for a new conversation. So still life at 80 is, it's a marvel. Nicholas uses these key places and objects and relationships in his life and each of the stories he tells about them kind of, well, they weave together and bring us closer to his experience through time and some of them are adapted from past essays, but they're honed and developed for this new purpose of showing us his process of becoming and what that looks like from the viewpoint of 80 years old. He just turned 82 a week ago, happy birthday. But I was just fascinated by the stories that continue to resonate for him, the moments that keep telling and how he chose to tell them in this context. And there are stories of the writers in his life and he's had this whole lifelong relationship with literature and there's anecdotes with Updike and Baldwin and John Gardner and more and those are filled with love and there's no way to read those parts of the book without lamenting the writing culture of the past. We'll say it's recent-ish but not recent enough. I mean, I do my best to try to invoke that world through this show and the conversations but I know it's not the same. Not like when the words and the books really mattered. Anyway, it should go without saying. If you've read any of Nicholas's previous work, his books or his essays, still life at 80 is a beautifully written book. It just demonstrates utter control of the writing craft and tone throughout. For me, it's just a joy-reading prose like this. The thing I'll say would occur to me when I was editing the episode. The book begins with a chapter that sort of recounts seven homes Nicholas has lived in and while it's engaging on its own and filled with humor and fondness and all these little details of these places we call home, which is so different for me, somebody who's lived in the same place, almost my entire life. I think what he's really doing is welcoming us into the home he's made of language and that the writing itself is the house that he's built and resides in. Still life at 80, it just beautifully captures a writer's life and the life of writers. So go get it revel in the writing and the time gone by and all the literary stories and just the perspective that a man can bring to his life. For my part, I was really happy to get to sit down with Nicholas again and go out to lunch with him and his wife Elena. It was my first trip to Cape Cod. I had a biotech conference in Boston that I set this up around. So I left first thing in the morning, took two hours to get to his place. We had a wonderful time together, a great lunch, great conversation for the three of us and then I had a six hour drive home, which was all worth it. It was grinding, but it's a small price to pay for getting to be part of this world, you know? Now as caveats go, there is this dehumidifier. We've recorded down in his basement. There's this dehumidifier that kicks in around 15 minutes into the conversation and runs for about 15 minutes. I had to sample that out, but you're gonna hear like audio artifacts and the tone of the voices change a bit when we do that. And when he talks about his father and business succession, he actually means his grandfather. You'll figure that out in the context. And I mispronounced Ella Jayak and I called it a Lee Jack and Nicholas was kind enough to pronounce it correctly, twice without directly correcting me. It is not as bad as when I mispronounced PG Woodhouse's name with Robert McCrum, which still burns me, but still I figure I should own up to it. Now here's Nick's bio. Nicholas Del Bonco is the author of more than 30 works of fiction and nonfiction at the University of Michigan, from which he retired as the Robert Frost distinguished university professor in English. He was director of the Helen Zell Writers Program and for 25 years, the Hopwood Awards. As the founding director of the Bennington Summer Writing Workshops, he created the Low Residency MFA program. He is a recipient of the JS Guggenheim Memorial Fellowship and was twice awarded the National Endowment for the Arts Grant and Prose Fiction. He has served as chair of the fiction panel for the National Book Awards and as a judge for the Pulitzer Prize. With his wife, Elena, he divides his time between Manhattan and Cape Cod. And now the 2024 virtual memories conversation with Nicholas Del Bonco. (upbeat music) (upbeat music) So tell me what you wanna know. - How'd this book take shape? - You know, forgive me, I'm actually thinking. - I do that today. - The shape itself was an issue with which I consciously grappled. It is, as you know, a three-part inquiry. And it is more carefully wrought than I hope appears on the first reading. But the shape is more of a mosaic than it is a chronological continuity. I should backtrack a little by saying that I had promised myself long, long ago that I would never write a memoir as a friend and describes it. And by and large, I have relatively little use for the kind of autobiography that begins. I was born in such and such a day. My parents were, and our address was. And so there's nothing specifically chronological about it, or even on the face of things, logical. It has more to do with matters that concerned or concern me. And therefore, the larger answer to your question is that taking shape was an after-the-fact consideration. I didn't really know what I was doing. It began, and in fact, we're in front of it, I think, with my rediscovering a long text that I had produced at the Auguste age of 11 about the history of art. And I read it with incremental astonishment at the nature of this studious little boy who removed the difference between Jakob Von Rolestel and his teacher Mindale Tobima, how that came about caused me to think. So that was the first thing I had. And indeed, the first thing I published as what turned out to be an extract from the final text, but it was a 40-page disposition on my life in art. And once I'd begun that, I began to consider the idea of going on in that vein. And some of it is cobbled together, previous memories, previous essays even, so that after I was in it for a few months, I realized I probably had a book to hand, all of which is a long way around to answering your question. And by the way, as an aside, I should say, I'm very grateful for this occasion, principally because it's a chance to see and talk with you again, but also because it's the first time I've talked about the book. And therefore, I realize this question might be asked of me. - I'm glad this is a rehearsed book. - But it's going to be less tolerant. So indeed, the book is going to technically be published on September 3rd, and that evening, I'm going to give a reading from it in the local library here, the Well Sleep Library. And by that time, maybe I'll have a can here answer or a quick one. (laughs) The short, and now perhaps distillate the response is, it took shape inadvertently. I didn't know that I was going to write such a thing when I began. The pieces began to fall into place, and a lot of what I ended up doing had to do with placement. As you know, the first beat of the book is about the houses I and we have lived in. And the last beat of it has to do with certain objects, themes of this world, which was the original title for the whole. You've seen and photographed all three of them that I focus on at length. And I am still surrounded by these things, and hope to be a while longer. And so, as a memoir, to begin with a discussion of houses and end with some art objects, is peculiar or at least particular. And that's the sort of book I found myself writing on the way, and by the way, I began to ruminate on the business of autobiography and memoir composition as such. And so, there's a good deal of that and this text also. - And the people. There's a lot of the mentors and other figures. - The people, my life has been, by and large, engaged in literature as a reader, as a teacher, as a writer. And it seemed only appropriate to limit the folk I talk about to writers. There are other people in my life or where whose emphasis was elsewhere, but not so for this book. So it's a gallery, if not a galaxy of fellow travelers. - And you mentioned the three art objects. The finale of the book. We're sitting in a room surrounded by books, including a whole bunch of your own. There is a point late in the book where you mentioned selling the house in Michigan and deaccessioning and the notion of getting rid of books. And because the moment you started with the getting rid of things, I thought, well, eventually, he's gonna get around with the books. What goes into actually deciding I can part with this? - There were two such seizures. The first, which I don't write about, had to do with our departure in 1985 from the house in Vermont to the house in Ann Arbor, which we called home for 30 years. And early on, I had been, as many young writers, are busily accumulating books that mattered to me. We sold or gave away or mostly traded because there was a good used bookstore near us. I think something like 4,000 books, because when I priced what it would cost to move the whole damn thing to Michigan, there wasn't a truck large enough to be cheap enough to make any sense of it. So I had a spasm of shelf clearing in my early 40s. And I realized, in fact, after the fact, that of those 4,000 books, there was only one that I really missed, because I really wanted to consult it again. Excuse me, what's the book about the children's crusade? I can't remember either the title or the author, therefore we don't know the name of the title. But that was an instruction, 4,000 books, which I could either replace at need or consult at need. And suddenly, there are still many books around me, as you can see, the volume of them seemed less consequential. The second move, which is the one that I refer to in still life at 80, was more painful, partly because I had made a not so small habit of acquiring signatures in books from friends, or acquaintances, or encounters. And I had well over 1,000 signed books that were probably displayed on my study shelf. That's a room that you hadn't been in, 'cause it was in Ann Arbor. That I did sell, or the majority of it, there were a few works by a few friends that I couldn't bring myself to part with, but the fact that I'd once had Tony Morrison or Saul Bello sign books, to me, seemed less consequential than the Nobel laureates would to others. And in order, in part, to find out it's retirement, I simply disembarassed myself of them. I regret that. Had I to do it all over again, I probably wouldn't have put those books up on the block. But there are also two or 3,000 other books that fortunately, because I had a little local reputation, and Ann Arbor Library was happy to take them from me. But I missed them. My mother, who was a very literate person, and who had been surrounded by books in her time, did say to me and my brothers, they can take everything from you, as had been taken from her and her family in Germany. But they can't take what you carry on your head. And indeed, what you carry, or is the title of a short story of mine, and what remains is the title of a novel of mine. And I think that's true, or at least it's a truth by which I've lived, that if it's in your head, it doesn't have to be on your shelf. - I'm going with Primo Levy as the quintessence of that, being able to recite Dante while he's in the concentration camp. I kind of figure that's the things we have to have on. - Absolutely, and thus far, though I may be deluded, I think I still have it in my head. Not all of Dante, but I can give you the first lines. - Yes. - And so the actual physical objects mean a little less to me than having been in their presence and carrying them as an abstract entity with me. That said, I regret it. And have we space enough to have those 8,000 words? Have those 8,000 books back for Vermont and for from Michigan? I would probably be pleased, though I think my wife would be less so. - You have a storage building out to the-- - Right. - It reminds me of Otto Penzler, the great mystery and crime fiction collector. When I recorded with him, he had no heirs or has no heirs and decided he would rather sell the books while he was alive than know that something is going to happen when he's gone that it's all gonna be broken up. And so he had, he'd actually built a house in Connecticut, solely to accommodate his collection and it's now largely empty. And I asked tentatively, do you regret? He said, "Oh, no, I regretted it the moment "I made the decision." I'm like, "Okay." So yeah, he'd tell them to a small amount, which is still probably more than our libraries combined. But yeah, there's a sense of, again, what we accumulate over the years and how easily that's demonstrated by books on a shelf or art on the walls. But I guess it's an overarching question about the book and how it took shape is, what did you learn? In the process of writing and the process of, I don't wanna say, well, we'll say editing, putting the book together. - It's a truism and possibly correct that we are our own risk critics and don't accurately assess what we produced. But what I think I learned and what struck me after the fact, rather than during the act of composition, was that the book is, and you can tell me whether you concur with this, essentially an act of gratitude or of pleased reminiscence. It's not a list of complaints or what might have been or what I didn't achieve. It seems to me to be the record of a man who is grateful for having made it to 80 and with relatively few personal or private complaints, there are public ones scattered through the book, of course, it's impossible to be a sentient human being in our time and not anxious or angry about what goes on elsewhere. Nonetheless, I think the book is a record of content rather than complaint. - You mentioned at one point, the realization will say that your mode is elegy and I don't know how much of that threads through the entire body of your work or whether you see that as something that progressed further along and whether this is a sort of culmination of that legy act mode. - You are a close reader. This is my 32nd book. - I have to catch up, okay. - And though I'm working at other and new stuff, it is a kind of recapitulation and reconsideration so that elegy is almost inescapable. I don't think that was true of my early work. Among other things, the first person pronoun didn't enter in or when and if it did, it was a wholly invented eye. Probably took so my first work of nonfiction, a book called Group Portrait, which came out I think in 1982 before I used the first person pronoun and allowed myself to be part of the party. So the elegy act mode or the retrospective one for I think predictable reasons has entered in increasingly and now both my fiction and nonfiction partake of either personal or public history and what went on in the past. I can reconstruct the 1960s a lot more accurately and I can report on the 2020s in terms of language. I mean, I was just with grand orders as I told you earlier and for the piece of fiction I'm trying to compile. I wanted music to be an important component and I don't really have any difficulty describing the work of Schubert or Mendelssohn. I mean, I may not do it well but I know something about what I'm doing. I had no idea what singers and what songs are of the present moment and my 14 and 16-year-olds gave me names that I'm surefully. - A plebeism but now you've got a-- - Right and I'm checking on the spelling with them but they don't signify, why am I saying this? The contemporary moment needs less to me than the ones I've lived through and by now or the ones that anti-dated my life. - Last weekend after Jenna Rolens died, I went back and watched the movie that introduced me to her and Rilka and Sati, another woman by Woody Allen and turning 50 is the great cataclysm back in 1987. So and what it means and then how you look up at your life or look around and realize where you are and what you've done and it put me in mind, I had just finished reading your book and thought 50 used to be that moment. For me 50 was life-changing but by accident, not in any sort of, this is a milestone. Looking back at those other moments, those things you thought mattered once upon a time and then seeing how that-- - Well, Jenna Rolens, I think of her mostly as a figure in the work of cats of it. - Yeah, these things were cats of it. He's not gonna introduce Woody Allen 'cause I'm an addict to you from the Northeast. - And for me, of course, who's slightly younger than she was, she represented beauty in full bloom and sex barely disguised as a demon. Barely disguised, a smolderingly present. - Smoldering was exactly the word I was about to talk to. - So she's a remarkable memory. I would have some trouble in terms of tanelapse photography with her present image and hadn't seen her in actuality, certainly, or on screen for a very long time. So for me, she's permanently young or not young, but mature in that way she incandescently was. - That gap between promising and distinguished as you can put it in her book. - Yes, I did publish my first book at the age of 23 and I'm now almost six years beyond that. And that's a longer span than most authors have. As I also say, about the gap between being promising and being quote distinguished end quote. The trick is only to navigate the 50 or so years in between, which is called one's productive life. - And for your work, especially in the nonfiction books, which is when we first recorded back in 2017, I focused on lasting this and. - Maybe the young of you. - Yeah, the young authors who died prematurely. What did that sense of time and stature and reputation first take hold on you? That attempted understanding it and what it meant. - How composite were you of it when you were starting out as a writer, I suppose? - I've shown you the photograph of Max Eastman here and I write about him in the present book. That's mostly a reprint of or a record phrasing of a much much earlier reminiscence I wrote, basically just after his death. Max Eastman, who was in his 80s when I was in my 20s, represented a kind of model for me of what lasting this might consist of in his 20s and 30s he was in effect a household name because his friends were, I mean, he was one of the co-editors, founders of a magazine called The Masses, which in the late teens and early 20s were crucial. So the political scene, his friend John Reed was part of the 10 days that shook the world. He used his title about the Russian Revolution. And so Max had a huge visibility of him in his childhood or youth. And by the time I knew him, he was kind of in exile or at least a retreat that I don't think I understood it at the time, but if you are fortunate enough to live to your 80s, yourself by date has passed. And so I've been living through and with that for what now feels like a very long time. America is kind to its youth, pays attention to children year by not even by decade, year by year, probably the most salient example for me was that of Bret Easton Ellis, who was my student at Bennington in the year that he was producing less than zero, which made him thoroughly famous. That's 40 years ago now anyway. And his reputation, I think of J. McInerney also, his reputation though it has been sustained in a certain sense as altogether altered. I don't think there's any example of a long lasting career which doesn't entail change. If you think of just shift the artistic expression, if you think of the visual arts, probably the preeminent example of that is Picasso who announced himself early on and did up as the most famous octogenarian in the world of art. But that too entailed change and a history of fresh starts and shifts. So I was fortunate. I think it's fair to say fortunate in my early 20s my work was noticed. And my picture was in magazines and they made a movie of my first novel, et cetera, et cetera. And in a certain public way, it's all been downhill since, which isn't to say that I think that my work has diminished just the attention to it has. And there's no point in grousing about it or even trying to deal with it because it happens to everyone with a very, very few exceptions. And look at Alice Munro for instance, when she died, she was at the absence of acne of respectful attention. And her career has all together altered post-missily. Some of that is related with some people that's related to personal life aspects. I think all of it is related to this. But that sense of reputation waxing and waning. The last time I was in Massachusetts, I recorded with Marana Comstock, whose grandfather was Conrad Burklevicci, who I'd never heard of. And I read the introduction to this posthumous book of his and all the press that's written about him in the 30s and 40s makes him out as well, it reminded me of Stephen Zweid being the biggest writer in the world and disappearing for decades after his death. - And now coming back. - Yeah, about chess stories, one of my all-time faves now, but Burklevicci is another one. Reading the pros is absolutely luminous. And yet, this guy who was a huge bestseller in his time disappeared. In that case, there's also weird political ethnic reasons that things happen to him, but. - The political and ethnic reasons are the ones that just are with considering it. I write in this book, as I have written before, about an old friendship with the now, our last long-dead James Baldwin, when Elena and I really knew him because we were nourished neighbors in the south of France in the early 1970s. - He was in a, I think in a state of decline. - Can you describe it that way? - Yeah. - Partly it was political because his heirs and societies thought of him as insufficiently radical. Partly it was because he was away from the well springs of his work. But Bullburn was, he was never wholly irrelevant or dismissed, but he was a minor figure by comparison, certainly with what has happened to him since. And this year, his centennial, I mean, it's impossible not to pay attention to the work of James Baldwin. And I think even though he had a healthy ad-11 of ego, he would have been surprised by his posthumous reputation. So it can happen. I mean, we deal with the obvious instances every day. The only line that Keith wrote that's entirely wrong is the one that he used for his epitaph. Here lies one whose name is written in water. I mean, everyone pays attention to Keith's in a way that no one did during his life. Think of Van Gogh who killed himself at least in part because he was unable to sell any paintings. I mean, that's a reductive assertion of course, but his reputation today is enormously other than that which obtained during his life. So it can happen that reputations increase rather than decrease. But by and large, the instance that you provided is the common one. Somebody who is of consequence. - Did it give you any comfort knowing that? - You could talk about again, that diminishment of attention paid to your work. Knowing that that's something that great writers have gone through any comfort whatsoever. You can still burn your asses in terms of, you know, they really should have jumped on this novel of mine. (laughing) - I think the feeling of being passed by having been the person who got prizes and becoming the person who gives them, but doesn't restue any longer. That, as I say, is almost inescapable. And in the natural order of things, the reaction to it is what interests me more. It used to bother me in ways that it doesn't any longer. When I was in my 40s, 50s/prime, I was always sort of arm wrestling with the person who was ahead of me in the line. By now, if not amused by it, be amused by it. It doesn't bother me in order that it did before. So, yeah, there's a kind of comfort in that. - And did the example of Baldwin uptight, some of the other writers you mentioned who were way up in the pantheon, there's a degree to which not a lot of people read uptight today. - It's not a degree, it's an absolute-- - Okay, I can say it's straight up, yeah. - But it's kind of fate in his death or since then. - John was very conscious of his standing in the willy use as it were. I mean, I remember sitting with him on a beach on what has been your way back when and in the height of his ascendancy. And he kind of drew in the sand, the size of Henry James, the size of Philip Roth, the size of John uptight vying for them. He was probably excessively conscious of his standing. But I don't think he ever would have predicted, I certainly wouldn't, that he would be so superannuated so soon. People were saying that the rabbit quartet was going to be the record of America in the fifties and sixties and now nobody reads them. It may come to pass if he gets the kind of biography that he deserves that people will resume paying attention. But boy, that foot race with Philip Roth is when he lost and by a long job. - There's a question I've had with other guests as to whether Roth survives another 20 years. - I doubt he will. The one I was close to and a colleague of adventure was Bernard Malamud who's also sort of gone into the, if not the absolute oblivion into a steeped climb nobody's paying attention to him or reading him any longer. I think some of his work may return and be revered again as it was in his lifetime. But he's basically all of them. Norman Mailer doesn't sell anything. - That's watching the bellow documentary on PBS and you get his aficionados among older white male authors and then you get a black professor and a woman coming in with. Yeah, let me tell you some things about sell bellow and the writing and you realize. - Exactly. - Yeah, not just in a PC way but in degrees of a lack of empathy towards people outside or in certain ethnic groups or in it. - I think part of the rush of modernity which is to say the speed at which reputations are made and lost has a course to do with our technology but the pattern you've just been describing and we've been discussing I think has accelerated sense. I mean, the names we've named, bellow, mailer, uptight, Roth, et cetera, all had a longer shelf life than this year's superstar will. There are reputations that ascend and descend more rapidly than they used to. - And more around book contracts and figures and Instagram followers. - Exactly. Survival, I guess, has always been my vibe in terms of trying to figure out what actually lasts and what makes something last and we know so much of that is accidental in its way. But as you put it in the book, the body of language enlarges, you keep at it despite years, despite, you know. - I do, I did this morning before we met and I will again tomorrow but it is more private than a public act now. I mean, there was a time when I was convinced that, you know, with the publication of each of my books, the world would stop turning nuclear disarmament would be declared. - Finally, don't make no resolve it for us. - Exactly. I no longer delude myself. It makes any kind of public difference. I comfort myself at the desk by the pure pleasure of being there. - Does this book make you reevaluate your parents? - Not really because I didn't really write about them at length or my brothers or, you know, my other loves. I kind of left that off. You don't include your father's momentary regret or at least a question of whether he, what he would have done had he become an artist. - You really have read it closely. I think that is true. - Do I look for regrets everywhere? So that's about it. - My father is more a part of my consciousness than other family members in some important ways because among other things I try not to look at myself in the mirror much anymore, but when I do, I see his face. And he died at 98 with the motto that a painting a day keeps the doctor away. And so I was quite conscious of him in his older age and I can measure myself against it in a way that I can't in terms of my mother who died, what now seems young at 61. But in some ways he enabled my profession because his own disappointment of not having been a professional artist kind of allowed him to encourage and even admire the fact that I was trying to become one. I didn't have to go into the family business or become a lawyer or a doctor or an Indian chief, whatever. He valued the arts from a respectful distance. And so when I entered the ranks of professional artistry, it pleased him rather than-- - You're an air-to-well son. - Yeah, right. - And seeing that face but also seeing him, knowing he again made it to 98 in your own race as the years go by, would he have gotten who you are, who you are now? - Do you feel that's paralleling right along? The physiognomy? - He was raised in a, I mean, I was raised in a traditional family structure, certainly, but he was born at the beginning of the 20th century and I think he had fewer options. His father ran a business and it had been his father's business before him. And in the way of such things, it would have been the case that my father's elder son taken over. My father's elder son, my uncle, either had or feigned a nervous breakdown. And said, "I can't do this." And he was a very, very intelligent person and basically shunted that responsibility after his kid brother and life, dad. So I don't think there was really ever a time when my father seriously contemplated a life father from the one he lived, at least until his retirement and in retrospect, meaning he willingly sheltered the duties of middle class responsibility. And as I write his, my mother used to say, "We're not rich enough "to afford anything other than the very best." And she meant, I mean, hers, her standards were high. Both of them came from that category of German Jews who didn't really quite believe that Hitler met them and who were surrounded by, if not luxury, at least, substantial kind of thingness. There were objects everywhere. - Can you say the trappings, the trappers? - Yeah, exactly. So a long way around saying that I don't think my father really, until his six years ever seriously contemplated the idea of becoming a free spirit and an artist and what have you. He was given the Vanda Yara to travel in America before he took over the range of the family business, but it was clear that he was going to. I can only speculate as to his regret. But he lived a happy life. He was a contented sunshine man, as they used to say of him. And I don't think he seriously second yes, his way of being in the world. - How has your writing changed? - Some years ago, I republished a series of novels that I had written in the late '70s and early '80s that became the Sherbrooks trilogy. There were three books, Possession, Sherbrooks, and Stillness, and they were individual sequential texts. Dolki Orka Press flatteringly asked me to, or said they would like to reissue them. And I said yes, under the condition that I could rewrite them. This is meant to be an answer to your question. So that's probably the only instance in which I was thoroughly conscious of that sort of analysis. I read those three books and because, among other things, they agitated the computer. There were no files that allowed me to reproduce them, I had to retype them, in fact. And so I paid close attention to my youthful self. The good news, I think, is that I'm a better writer now than I was then, and the bad news is the same. So I spent a lot of time reconsidering or revising, reviewing what I had written when young. I think my work is a lot less show-offy now. And I know that it was show-offy then. Full of, to use a word I would've used, wrote a montage. And so I've come increasingly, I think, to embrace the notion of power in restraint. And that less is more, my books have gotten shorter, and less flowery, and less obviously experimental. That probably is a characteristic of older age and artists, that they tend to be, I want to say reductive, though that word applies. But when you think of, I'm not comparing myself to them except in terms of age. When you think of the old Monet, the old Rembrandt, the old, a lot of stegner to come back to literature, almost without exception, they get simpler as they get older. And I think that's a model I'm attempting to follow. - I think we talked about it previously, how Roth's books also, by the end, he's under 200 pages of page, just compressing and compressing. - Also, Remus, I should have mentioned, when you brought up the books you had to give up, the Philip Roth Personal Library in Newark, I got to visit and record when they were launching it, and seeing those dedicated books that he had, and the notes from D'Lillow and all these various other figures are writing to him, was kind of a thrill seeing that. But he also had to give to Newark because he had the keys. - He had the keys to city. - You know, that city, everything, and I don't him a bunch. But when you mentioned, well, getting rid of so many books, I do have to ask the, I think David Lodge brought this one up in a novel, a weird incident where a character is accumulated for this. Great book that you haven't read that you're still thinking, oh, yeah, I should get to that before. - X. - There are any number of them. I mean, I was a college professor and putatively learned but the limits of my learning are achingly manifest to me. This is complicated in older age by the certainty that I've forgotten, no matter how good my memory, the essential thrust of many books that I did, in fact, read. There were some years in which I was a judge of things, meaning the National Book Award, or the Pulitzer, or the Penn Faulkner, or whatever. And I would read in those years something like three to 500 works of fiction that came out each year. And each year, I would know with total certainty that I wasn't going to encounter something the size of, say, War and Peace. But I have more and more told myself it makes sense to reread War and Peace, which in fact I did because it was translated. - See back there on the other shelf, the Avira Voliconski one, yeah. - Yeah, exactly. You do notice. So between the books that I haven't read and the books that I haven't reread, there's a lifetimes worth of learning. Still that awaits me. I have about five books to read in the next couple of weeks which I won't enumerate because it's embarrassing. I haven't read them yet. And I know beforehand that none of them are going to be, - Less changing. - Whereas if I were to pick up Bleak House, it probably would be worth the weeks that it would take me to finish it. Actually, the book that I'm reading at the present moment, which is called "Use of Fire" by the non-engineerian Michael Corda is about poets in the First World War. He spends a little more time than he needs to, I think, on the personal charm and beauty of Rupert Brooke. But there are a couple that I have paid attention to, Robert Graves and Secret Sassoon, who really do repay attention. Wilfred Owen, who was essentially unimportant and unknown during his lifetime and is now, crucial to our reconsideration of the First World War. And a couple that I really hadn't known worth mentioning, Alan Seger, et cetera, Isaac Rosenfield. And that's an interesting thing to me and it attaches to what we were discussing earlier, the rise and fall or the lastiness of reputation. Rupert Brooke was hugely important in England during his brief lifetime and now has been reduced to a tagline. And everyone resides to the degree that anyone resides, Wilfred Owen, who died more or less in total obscurity. So, going back to what was produced when there's a question, a book by Robert Graves to which I keep returning it as the Marvel title, "Goodbye to All That." And he did turn his back on it, but he produced an enormous body of work. - You're written poetry? - Have I written poetry? - Or poems, we'll put it that way. I think Clive James told me he prefers poems over poetry. - I have. Only by accident. - No, by intention. Early on, like any self-respecting undergraduate, I wanted to be either a poet. - Yeah, a poet focusing your movie star, I think you mentioned in the book. (laughing) - I did, in fact, write a novel called "Consider Safar Burning" in one of those early effusions to which I, glancingly, referred just now in which my protagonist was a poet, and I allowed myself to produce her language with a certainty that it would be printed, which one wouldn't feel about one's poetry. - You know, I'll tell you, I've recorded with Jonathan Galassi many years, not a bunch of years ago, and he had a book where there was this great poet, and he wrote the poetry for this person. I'm like, how confident were you about that, Jonathan? 'Cause, you know, you're kind of, this piece has to be something that is meaningful enough that it stands in for something world-changing, and you're kind of taking that on yourself, but anyway, cool. - I think Maggie Dreibel's sister just died. - By it? - Yes, AS by it, in the novel possession. She allowed herself to compose the poetry of the dead figure there. So I wrote some poems there, and I wrote or tried to write a novel recently, discarded it relatively early on in which, and it became a short story where there was poetry in it, a long way around saying, "Yes, I think anyone who's serious "about language must revere the work of poetry, "but it is brutally difficult to produce "in any meaningful manner. "As a child, I wrote lots of dog oral, "then I tried to write in a romantic verse. "I don't think I had the ability to just sever "the private effusions from the public result, "and so poetry, we didn't present itself. "To me as a real way of being a writer, "but I do revere in work of poets and some actual ones." - You mentioned a book failing and becoming a short story. What's that moment when you realize something doesn't work? - Is it a curious moment which I think any writer has, and it really doesn't have much to do with how hard you work at it. Sometimes you just know you're on and you're hitting on all age and everything is lying down affably on the page and saying, "Don't change a word." And there are other times when you recognize that what you're doing is merely or has its best dutiful and that it's dead in the water. It usually takes me less long to recognize that it's dead in the water than it did with the text to which I just referred and it was a novel that I completed and realized that there wasn't much point to it and then it was a function of my dutiful act of composition. There's a wonderful story about that told by, I think it was Sir Edward Garnett who was the dutiful kind of writer I'd just been describing and who's most famous still for the lady in the Fox. He was writing it 500 words a day and it wasn't anything actually there except the duty I've just been discussing. And one day for reasons that he was never able to identify afterwards, he woke up, maybe it had been the pleasures of the night before or the after effects of the meal or the slant of sun and he sat down at his usual place on a table under an oak tree in the garden and he just wrote and wrote and wrote, working his way through pencil and pen and sheets of full scap and for I think 18 hours uninterruptedly and he had broken the back of the book. He'd written maybe 40,000 words which is an unthinkable amount and went to sleep for a very long time, woke up and put 500 words at a time towards that. - Dutifulness. - The completion and what's interesting about it is that when he shared the manuscript of friends they couldn't tell what was the actual thing. - The ecstasy versus the well. - The duty as opposed to the delirium. And I think that most of us can recognize that most of us can recognize when we've been in that condition of amazingly fortunate eloquence or just inside the work and happy with it and not needing to do much to it, except minor tweaking and cosmetics. And when "Pare Culture" we are just sort of putting in our time so I put in my time on a book which was a mistake from the beginning to the end. - You recognized it as opposed to trying to inflict it on the publisher so that's-- - Of course it helped that no publishers wanted it. - Yes, that'll be one of those. I never know how much I hate salability but how much the market matters when you're in the moment of actually writing something. - It doesn't, or at least it doesn't for me. I think probably there are successful authors who are successful precisely because it does matter and who know. But I've said this now several times and I need to repeat it of late and perhaps of necessity. I've come to find myself more compelled by what I'm doing in a private sense than in a public. - So let me answer, two questions left, at least on the sheet, which I'm sure will take us a while to me and her through, but there was a phrase you used in the book, the fleeting feeling of insufficient accomplishment that meant one thing to me and I think something else to you as you expand on it. Can you talk a little about what that-- - Well, what are you right about? - My sense of object failure? - Yeah, all the time. - You too. And I just, I can't imagine that there's any author who isn't visited by that feeling. I think I by now can take a pretty accurate reading of what I have done and what I've failed to do. And by and large, at least in terms of the more recent books, I'm content with what I've done. But, and I don't mean this to be falsely modest. It is fair to say that it's minor achievement. I mean, Tolstoy and Bolzak and Dickens I8. And, and there's no point pretending otherwise. More and more, I measure success in terms of the distance between intention and execution. If you come as close as you can humanly to that which you attempted, you can rest content with it. And if you've fallen far short, you shouldn't rest content with it and you should perhaps scrap it. The fleeting feeling of insufficient accomplishment. When I am recognized in the grocery store, or if I'm paying a bill, it's usually because somebody knows the work of my far more publicly famous younger brother. And I've gotten over trying to correct the record there and say, no, I didn't write that book on Melville. It was his. Only very rarely does somebody compliment him on a short story that he didn't write. How do I answer this except I've answered it briefly and perhaps sufficiently. The long one, the long reach and increasing certainty that one doesn't have it anymore is worth pondering. I mean, if you're a ballerina or a baseball player, you kind of know the results are visible. Yeah, the results are visible and the terminus is manifest relatively early on. I mean, there aren't any great baseball players at 60. And there is nobody who begins to dance at 50 who will establish a reputation. We can dilute ourselves as artists that we continue to grow as we continue to age. But I'm not so self-deluded as to think that my work will displace the work of the names we've named. - So look, those same lines. There's a moment in the book where you're looking at funeral plots and they offer to bury you next to Edmund Wilson who's on the shelf over here and I want to make sure at least there was one piece of his, so it was an assign a disrespect. You choose not to. Oh, sorry, go on. - I must correct that. We're looking at funeral plots for Elena's parents. - That's right. - And her father, as you know, was in fact a famous cellist and indeed quite famous in our little local town because he brought young talent chalice from all over the world to study with him. And so there was much music in Wintry well-sleeved. And when Elena and I went to the town hall to bury him and his wife, the town clerk, once she'd identified, I said, "Oh, you know, burning was famous. "Let's bury him next to the other famous fellow." Edmund Wilson. I wouldn't have qualified. I don't think she wouldn't have invested too long there. But anyway, we said they may have known each other a little in life, but not so much that much of that line from Marvel. The graves are fine in private place, but none, I think, do their embrace. - Greenhouse and Wilson weren't pre-disposed to embracing underground, so since they hadn't above ground. So we found someplace else. - If you were to be buried, if you were to be buried near an author from the past or artist, not necessarily well-sleeved, but anybody you'd wanna be neighbors with for eternity? - We have actually more or less agreed that we will join that now-purchased family plot, so I know that the closest I'm gonna come to another artist that is in my wife underground will be, in fact, to my father-in-law. But who do I think of as eternally worth paying attention to in terms of epitaphs? - E-H is very good at having composed his own epitaph. You know, which was the last couple of it from Mark Quattrain from under Ben Bulbin, which may have been his last poem, "Cast a Cold Eye on Life on Death, Horse from the Past By." Not bad to one line near to the other epitaph that I will quote to you in this increasingly elegiac conversation. Here are the last one whose name is Ritten Water. I wouldn't mind Johnny Keats for a- - Neighbor. - Very neighbor. But interesting, isn't it, that I've come up with a couple of poets. John Dunroat, John Dunne and Dunne. (laughing) - I'm not sure which prose writers I would say move over a buster I wanted to ensure your soil. There are too many of them today. - I'll give you a real last question and try not to be as elegiac as I have been. What are you working on? What's looking forward for you? - I'm working on a novel. Well, first of all, I've got a couple of projects that I hope will come to public fruition that are more or less finished. I do in theory have a book coming out next year that will be the collective stories of Nicholas Dovlanka. I published a couple of volumes of them way back when and have been dutifully accumulating in some sense, one of which has a lot of poetry in it. And I think it's fair to say that I believe that when it happens that Dokky archive press is going. - I seem to remember seeing a listing for that. I can't remember. - Yeah, I mean, their intentions are good and there is a contract, but I will believe it when it comes to pass. For the three volumes in one of each short stories, I also have a novel that I love and have been unsuccessfully able or trying unsuccessfully to flog. That's a short historical book written in the voice of Kora Crane, the wife of Stephen Crane, who seems to me was a fascinating figure or at least she fascinated me. She was the first female war correspondent where he met her when she was the matter of the whorehouse in Jacksonville. She was married six or seven times at once or twice concurrently. But I think it's fair to say that he was the love of her life and his was very short. So I've written a book called The Work of Love, which I hope we'll see the light of day. What I'm working on, I think I'm gonna fall back on the time-worn trick of the novelist saying I'm not quite ready to just go through this. But at least you're looking forward. But I'm working on a novel that pleases me at the moment and I see you next. We will discuss it, we'll be looking forward to it. Right, Nicholas, thanks so much for coming back on. What a pleasure to be with and to see you again. And that was Nicholas Del Panko. Go get still life at 80, a memoir out now from Mandel Vilar Press. It really is a wonder. I hope I got that across to you in the introduction and through our conversation. And you should go check out Nick's novels, non-fiction books, essay collections. He's an absolute treasure of a writer and it was awfully fun to see him tackle the memoir or meme wire in this context. And his website is nicolasdelbanko.com but that doesn't look to have been updated for a while. He does not post on social media, which as we all know is for the best but I'll have a link to his website and his books in the show and episode notes for this one. You can support the virtual memories show by telling other people about it. Let them know there is this podcast comes out every few every week with neat conversations with writers and artists and cartoonists and translators and publishers and musicians and all sorts of other culture making people. You can also help out the show by telling me what you like and don't like about it or who you'd like to hear me record with or what movie or TV show or book or piece of music or theater or art exhibition, whatever. You think I should turn listeners on too. You can do that by sending me an email, sending me a postcard or a letter. I put my mailing address in the bottom of the newsletter that I send out twice a week, which you should sign up for. Or you can leave a message on my Google voice number. That's nine, seven, three, eight, six, nine, nine, six, five, nine. That goes directly to voicemails. You don't have to worry about getting stuck in an awkward conversation with me. And messages can be up to three minutes long. So you go longer than that, it'll cut you off. Just call back and leave another message. And let me know if it'd be okay to include your message in an upcoming episode of the show. You might have something interesting to share with listeners, but I'd never run something like that without the speaker's permission. So, you know, let me know. And if you got money to spare, don't give it to me. I mean, I'm gonna ask you for money when I do a Kickstarter for the book that I'm making at the end of 2024, about my 2024 podcast experiences and Instax photos, but that's coming later. For now, give to other people and institutions in need. With people, you can go through Kickstarter, GoFundMe, Indiegogo, Patreon, CrowdFunder, things like that where you can find people who need help paying medical bills, making rent, veterinary bills, car payments, getting an artistic project going. They might be caught in some tough circumstances and just a few dollars from you might make a real difference in their lives. So, you know, help out where you can. With institutions, I give to my local food bank and World Central Kitchen every month. Make targeted election contributions, but I'm a lobbyist. So that's part of my gig. But you can give to Planned Parenthood and women's choice and freedom funds and there are all sorts of other funds that are out there trying to help us make a better world. So, you know, I hope you will. Now, music for this episode is "Fella" by Hal Mayforth, used with permission from the artist. So visit my archives to check out my episode with Hal from the summer of 2018 and learn more about his art and painting. And you can listen to his music at soundcloud.com/mayforth. And that's M-A-Y, the number four, T-H. And that's it for this week's episode of "The Virtual Memories Show." Thanks so much for listening. We'll be back next week with another great conversation. You can subscribe to "The Virtual Memories Show" and download past episodes at the iTunes store. You can also find all our episodes and get on our email list at either of our websites, vmspod.com or chimeraupscura.com/vm. You can also follow "The Virtual Memories Show" on Twitter and Instagram at vmspod at virtualmemoriespodcast.tumbler.com and on YouTube, Spotify and TuneIn.com by searching for virtual memories show. And if you like this podcast, please tell your pals, talk it up on social media and go to iTunes, look up the virtual memories show and leave a rating and maybe a review for us. It all goes to helping us build a bigger audience. You've been listening to "The Virtual Memories Show." I'm your host, Gil Roth. Keep reading, keep making art and keep the conversation going. (upbeat music) (upbeat music) (upbeat music) (upbeat music) (upbeat music)