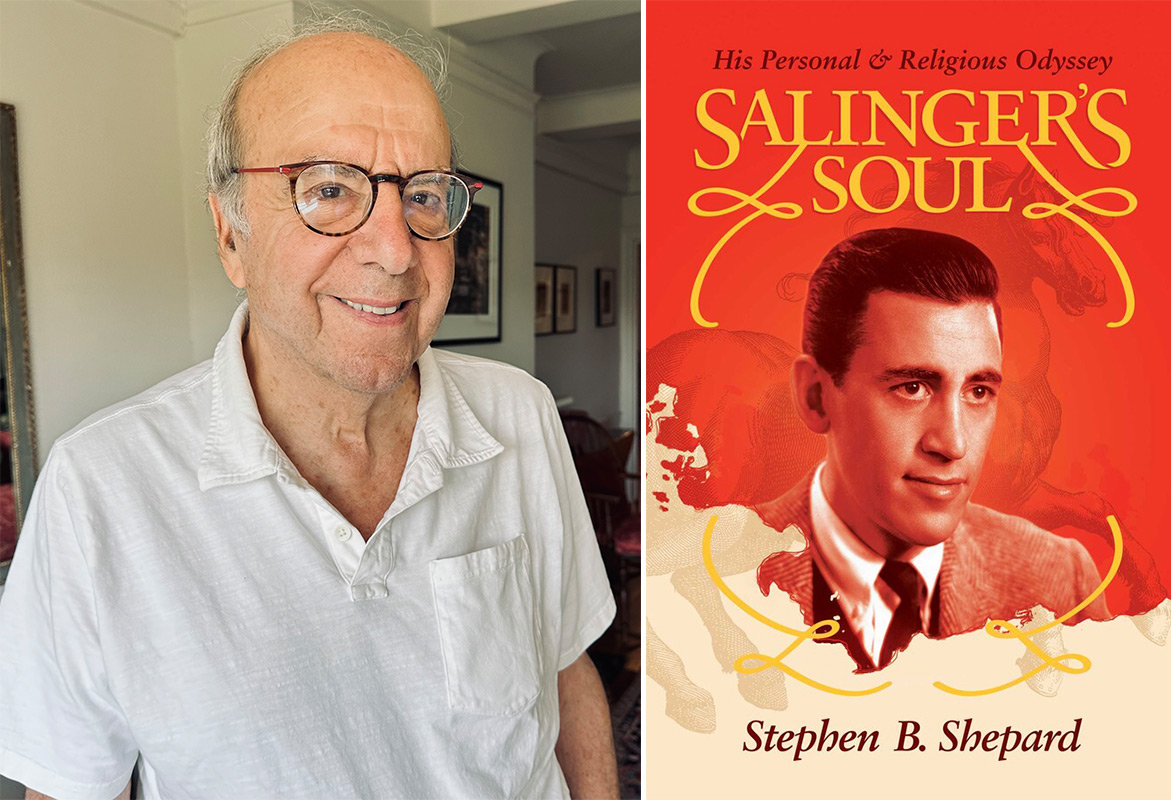

With Salinger's Soul: His Personal & Religious Odyssey (Post Hill Press), author and retired journalist/editor Stephen B. Shepard explores the life of JD Salinger and the hidden core of an author who became famous for avoiding fame. We get into why Stephen decided to chase this elusive ghost, why Salinger didn't make it into his previous book about Jewish American writers, whether he believes Salinger's unpublished writing will see the light of day, and why it was important that he approach the book as biography and not literary criticism (although he does bring a reader's voice to the book). We talk about the lack of sex in Salinger's fiction, the uncanniness of Holden Caulfield's voice, Salinger's WWII trauma, his rise to fame, search for privacy, abandonment of publishing, embrace of Vedanta & ego-death, and his pattern of pursuing young women, and how it all maybe ties together. We also discuss Stephen's career as a journalist and how it influences his writing, what he learned in building a graduate program in journalism at CUNY, the ways we both started out in business-to-business magazines (he went a lot farther than I did, editing Newsweek and Business Week), how journalism has changed over the course of his career, Philip Roth's biography and what it means to separate the book from the writer, and a lot more. More info at our site • Support The Virtual Memories Show via Patreon or Paypal and via our e-newsletter

The Virtual Memories Show

Episode 605 - Stephen B Shepard