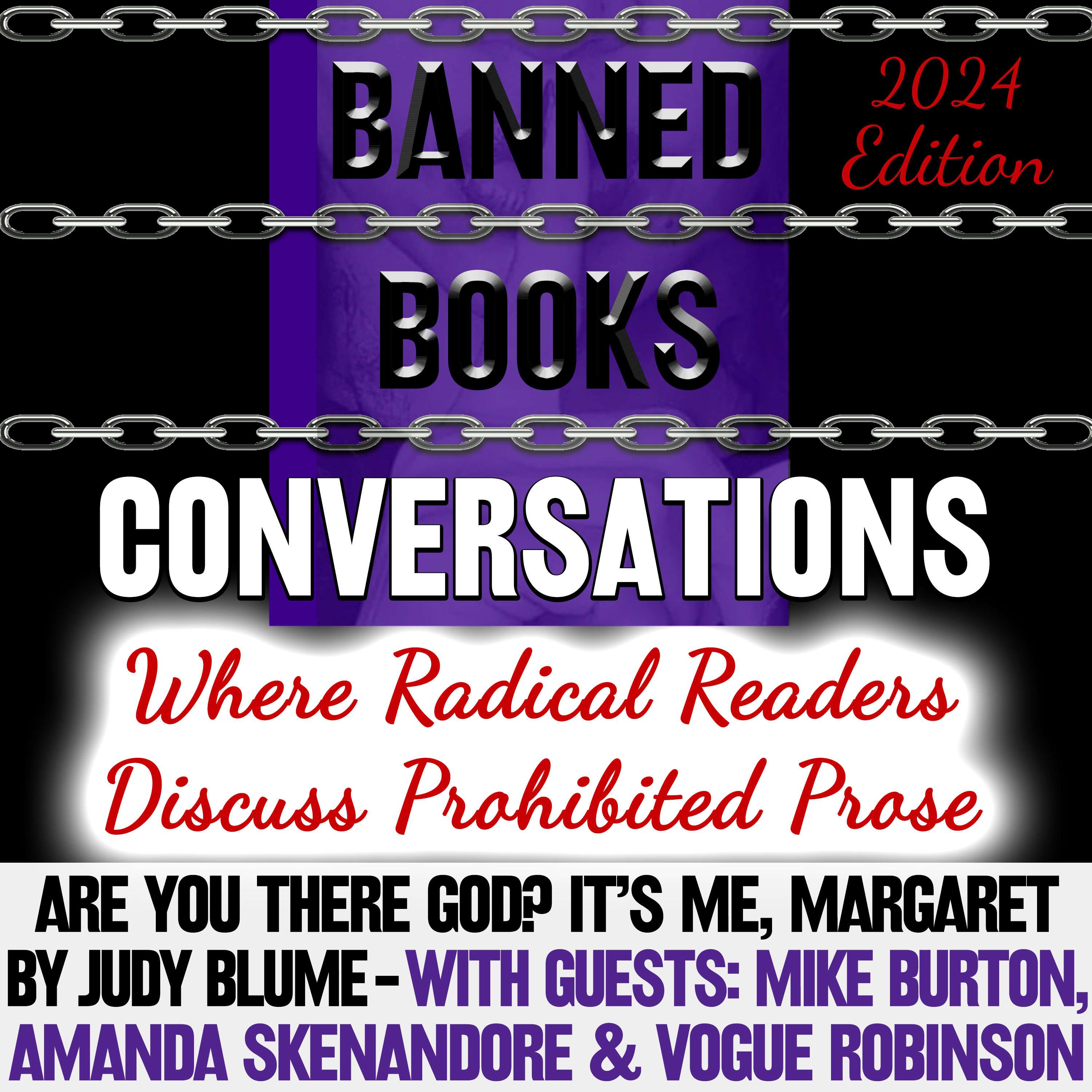

(upbeat music) - Meow, and welcome to the first episode of this year's Band Books Conversation. I'm your host, Tanya Todd. Before we get started, I want to give thanks to everyone who helped me make this series, What It Is, starting with JP Butler for his production assistance. Spider Dan of Spider Dan and the Secret Wars podcast for creating audio reels, Dave and Tony of Comics in Motion and the Ladies of Them On, who let me hijack the schedule all week and to one of today's guests, Mike Burton of Genuine Chitchat for his graphics and platform sharing. Now, we're all here to talk about Band Books, library works that have been removed from a school curriculum or the library shelf. Over the course of Band Books Week, this series will cover seven different books, the reasons they were banned and the value in reading them. The first book from this year's series is Are You There God? It's Me Margaret by Judy Bloom. And it may surprise you that this classic children's book is on the Band Books list, but before we get to that, let's meet today's radical readers. And I already mentioned Mike, so we'll start with you. Please tell us a bit about who you are and what you do. Preferably with the mic on. - Yeah, I'd almost never mute myself, so I'm very not used to it. That was a terrible move for the one of the first ones, meeting these individuals. So I have the podcast Genuine Chitchat, which Tanya has been on six or seven times. I was introduced to her in episode 97, so if people want to go back and listen to that, that was a fun one. But we also spoke about the Band Books conversations back in September 2022. And we spoke then about why Tanya started this, 'cause some of these conversations, we get to hear a lot from Tanya, but it's kind of the brainchild of that. That would be one that I'm especially gonna go back to and listen to to help with this, 'cause we're on the third edition, I think, of the year of Band Books. But yeah, thank you so much for having me on. It's been delightful watching from behind the scenes and just doing a bit of artwork-y stuff to help along. But yeah, I'm really excited to chat about this book. I've been so much, I've really enjoyed being a listener. So now getting to be a participant after so long, especially after knowing you for so long, it's gonna be a lot of fun. So thank you. - Boak. I was like, "She's gonna call on me next." (laughing) Nice to meet you, Mike. Yeah, my name is Boak Robinson. I am a poet, I'm an educator. As of late, my husband has been calling me a creativity enabler. And I'm okay with that, that works for me. - That's accurate. - Yeah, I was like, whatever, whatever works, but yes, I will help you do all of your creative things and clarify it. I served this Clark County Nevada's Poet Laureate from 2017 to 2019. And I am the first black woman to win the Silver Pin Award from the Nevada Writers Hall of Fame. I'm happy to be here. - That's amazing. - And Amanda. - Hi, thanks for having me. I'm Amanda Skinendorr. I'm a historical fiction author and a registered nurse. And I think most relevant to today, I'm a reader. I love reading, I love books. I love talking about books. And yeah, like I said, thank you for having me. And I'm so thrilled to be here with Mike and Bo. Thank you. - Well, Amanda, you've been a panelist on this series for three years in a row. What is it about the band books conversation that interests you and keeps you coming back? - Hmm, I, first and foremost, I think it's incredibly important that we're talking about this issue of band books. As I was thinking about this, I was reminded of another children's book that I read when I was a kid, there's a boy in the girl's bathroom by Louis Sacker. I don't know if anyone read that, but it was a great book. I still remember to it this day for many reasons, but one of the things was there was a counselor at the school and she's sort of helping them in character. And then one of the teachers launches a complaint, or not one of the teachers, I'm sorry, one of the parents launches a complaint against her. And the school has this, I guess like a meeting to kind of let the other parents voice their opinions. And what happens is this, our main character, he's had an amazing experience with this counselor and she's really changed his life. But, you know, so often when we have a positive experience with something, we're not saying anything. And it's the people who are upset about something, who are angry, who have a, you know, a bone to pick, who show up at these things, right? And as a result, spoiler, I guess. The teacher, the counselor is, she's fired from the school. So that has always stuck with me, you know, for 30 plus years. And I think that's why I love these conversations and why I think they're important. Because if the people who do not support banning books don't speak out and don't, you know, just raise awareness that this is happening. And, you know, not just happening, I think in the places we tend to think about them happening like Florida. But, you know, it's happening here in Nevada, right? Where I'm from. And Tanya and Vogue too. - Yes. - I wanna say that, you know, so again, I just think that it's important to be having these conversations and to raise that awareness. So I'm always thrilled when you put that out, I always jump on the opportunity to do it. - And I thank you for it. - Vogue, you're another returning guess. What is it about? Band books and the conversation around them that interests you? - I mean, I'm still thinking about the book we read last time in our conversation. I can't remember the name of it, 'cause you had to block it out. It was a whole trauma. What did we read, Tanya? - Out of darkness. - Jesus Christ. Yes, I had to crawl out of darkness from that book. But really thinking about the fact that I really wasn't censored as a kid. Like I just picked up the books that I wanted to and my grandma was like, cool, she's reading. My mom was like, cool, she's reading. So nobody ever took a book away from me. And when there was a book that my grandma didn't quite like approve of, she talked, you know, there's some, like there were some sex scenes in some of the books that I read. I've been a reader for a really long time. It's like kind of an advanced reader. So even when we found things that had sex in them, she would either have a discussion with me about it or just say like, I don't like that book. And that would be it because like I was also reading the Bible, which also has some scenes. So I think I just, you know, I'm on the side of people having freedom of choice and also to facilitate conversations because if we're consistently shutting people down because they think differently than we do or feel differently than what we do, then we're never gonna get to a place of understanding and then we're never gonna get to a place of peace. And I feel like that's a major component of the problems of today is that we just won't even have a conversation because a person thinks a thing. - And Mike, it's your first time. What is it that brings you to this conversation? - Well, for me, you know, I've been having conversations on my podcast for, it's been about seven years now. And so it's been something where I've always had the freedom to be able to speak about what I kind of want to a degree. And as I've met people like yourself when you speak about certain literature, I'm always like, I haven't read that. I've not even heard of that. And I wanted to make myself more well read. And so listening to a lot of your band books really piqued my interest and to support you as a friend and as a supporter of what you create. And it's just got me more and more interested by some of them. And, you know, in this one, I kind of cheated because with this book, there's a movie of it which I'd already seen. So I took the short, I read the book to clarify. I didn't fully cheat and I've got some comparisons. But I, it was one of those. And for a lot of my childhood as well, I would read books and be very excited by them. My parents had let me read anything, but I was never into things that had sex in it really. It was always like demons ripping each other apart or vampire stuff as like, yeah, a lot of violence. You know, my old, I've got older brothers and my parents were like, he can watch anything as long as there's no sex in it or like, you know, over the top drug use. So it was like aliens and Terminator and all these things when I was like 10. And it was like, I could take that and it was fine. So for me growing up, you know, I didn't really learn about book censorship and I've never grown up in a religious household or anything. So I never had any of those restrictions. And when I've gotten older and things and learning so much more, thanks to yourself, Tonya and other members of the Femon Collective, especially speaking about certain things that are going on in the world, not just in the book world, but censorship as a whole, my biggest issue with it is not saying no way should ever have any censorship. But when it comes to especially literature and art, it's one of those things where I think warning signs on certain extreme cases can be put on there. Like parent or advisory things potentially. But when it comes to actually banning, I'm against that. I'm just like, my thoughts are, if it's provocative, it can cause someone offence. And provocative things are the kind of things that you really need to be reading to find out other people's ideas either to challenge your own or to help you reinforce your own in certain respects or learn other perspectives of your own kind of thoughts. And I think provocative books do that. And you can't live your life without being offended, to be honest. So it's one of those where if you do pick up a book and it offends you in certain respects, if it's an extreme example, if it's triggering, you can put things in place to warn people of that. But overtly banning it, I think, is problematic because then it's, if it's caused this amount of offence to this group of people, then it can cause this amount of offence to another group of people. Eventually, you just kind of ban anything. I know the slippery slope can be considered a weak argument. But I think in books and media and art, something that's so subjective, I think it holds a lot more ground. - Thank you. - I know we'll talk about it. That's why I came on the joke. - So Amanda and Vogue, you may have answered some of these questions in previous episodes, but I feel it's worth revisiting the topics for those who didn't catch those episodes or those discussions or in case your answers have changed. So we're going to start with you on this one, Mike. Have you had an experience with a book that offended you? And if so, how did that affect you? How did you respond to it? - The only book that's ever offended me was the Bible, to be honest with you. I went to a Catholic primary school and again, my parents were not very religious at all. And so I asked certain questions about certain things. They only let us read certain bits of the age. I asked certain questions about certain things and they would tell me not to ask those questions. They would shut me down, my inquisitiveness and my desire for knowledge and things. And that's not necessarily a problem with all religion or even all Christianity or Catholicism, which is a Catholic school, but it was with the people there that caused that. So I put a very much a bad taste in my mouth and then I went into reading the Bible a bit more myself. And there were other things that I felt like didn't represent certain areas of what I viewed as what Christianity was and things. And that was throughout my teen years and et cetera and that kind of maybe challenged my own perceptions of religion, but an actual book overtly offending me, not from how my ideas spiraled from it and my experience from it, I don't think I have. I think that I've not, I'm not saying there aren't any, but it's even with films and things. I don't think there's any media content that I've consumed that's offended me necessarily. There's been jokes made at my demographic or things like that or things I like. Metalheads are often, there's jokes about that. And I'm like, ah, it's fun. Someone's making fun of me, but it always is in a comedic aspect, I think in that respect or there's a message to the art and it's not about me, those kinds of things. So I personally haven't come across it, but as Tonya's aware, I'm not the most well read. All the books behind me, if anyone can see it, in the video are all Star Wars books. So in the last sort of five, maybe 10 years, I've almost exclusively been reading Star Wars books apart from the last sort of couple of years. I took a big break from anything else really. Autobiographies and Star Wars books are now, they've been coming into reading other stuff, but I'm not the most well read person. So, you know, that might be why. - How about you, Amanda? - So probably, this always comes to mind when I see this question. So it's possible, this is what I have shared in the past, but I recall there was a book and it was describing a date rape scene that was not framed as a date rape scene, that it was just like, this is okay, that he just raped her. And that made me very uncomfortable and in a real like visceral way. But it happened where like I just actually mentioned something to the author, it was kind of uncomfortable to even say anything, but I did. But even thinking about that experience, like it's not something that I think, I wouldn't want that book banned, for example, you know? Or, you know, I don't know what kind of trigger warning you would put on that, like rape that isn't rape or you know what I mean or framed as such in this book. But, you know, so definitely there are things that, you know, that just kind of like punch you in the gut sometimes. And not even because what they're talking about, but I think more often it's been the way that something has been framed. But again, I would never want that, I would never want to like stifle the creative process, right? Like, I think those conversations, right, arising out of that, being able to say like, you know, when I read this, this read a lot, like they rape to me. Like, I think that's actually a healthy thing to be able to talk about because then, you know, it doesn't have to just be that thing, but there are all kinds of things like that where we can say, you know, this is, from my experience, this is how I saw it. And I think it helps in that, the broader discussion for people to be like, "Oh, I could totally see how it would be that way." Or, "I could totally see how that would actually be rape." Like, these sorts of things. And so again, like it's not something that I want to like tamp down necessarily, but invite the discussion about so that we can start to see things from different perspectives. - Particularly groups, are your friends. How about you, Vogue? - I feel like offended is always kind of like coded language. And so it's like different speaking, something that's offensive or inappropriate or if something is literally just specifically an insult, like a direct insult. There aren't that many things that offend me 'cause I'm just like, they're not talking to me. Like, that's just always like, I just have a nice little shield. It's like you're not talking to me. Or like, you're ignorant and that's between you and whomever. But I think in reading things, I tend to be pretty selective. Like, I tend to do a bit of research on what I'm going to read and I read things that I'm interested in. And so in that way, kind of I'm shielded, I think from a lot of things that maybe would offend me. And I think when it comes to like comedy or older movies, like my husband loves classic movies. And I'm like, oh, that's wonderful that you love classic movies. And those are movies where black people just don't even exist. And so I do, and I don't know if I would use the word offense, but it's like, I don't know if I'm as interested and leaning into like all these movies are not on my bucket list because I just wonder about the creator who decided that a world needed to exist where I do not exist. That seems a little messed up. So like I have questions, I would want to read up on the writer, the creators of those things, but I don't seek out things that I know are going to probably frustrate me. So I'm in my little bubble sometimes. I live in my bubble sometimes. - Hey, it's your world. You get to define it, right? So Amanda, is there a scenario in which you feel banning a book is the correct course of action? And if so, what is it? - Yeah, so I was thinking about this and thinking about my response last year, which is similar, but I would say as a general jumping off place, no. But I do sort of think a little bit about books specifically that are like how to self-harm books because there is a, like a scientifically documented phenomena of like, you know, suicides leading to other suicides within a community, or example, right? And so I have this like, what about this? But I think even in a situation like that where you have a book like that, or I remember when I was in college, like the big thing were these pro anocytes where you could go and find out like how to be an anorexic. Like, I think, again, I'm going back to this idea of the conversation in, you know, instead of like trying to say like, 'cause it's out there, this information is out there, right? Instead of trying necessarily to squash it, I think a better place, especially with something like suicide and real like self-harm things, it's better to just like to have the conversations, you know, not to try to like pretend like this doesn't exist. And if kids don't know how to do it, they're not gonna do it, or not just kids people, right? But better to see that it's out there, to know that it's out there, and to kind of, I think, address it head on. So a little bit like I said, a little bit different from my response last year, I think even those books, you know, that are, you know, explicitly telling people how to hurt themselves or others, I don't know that I'm against even banning those. - And Beau? - So I was thinking about different times where I've seen like the ideas of book banning show up, and I don't know if y'all watched the show "Severence", which is basically the work-life balance TV show, but it's on Apple. But it's, there's a book that one of the main characters reads and that book kind of unlocks him thinking differently about like his job and all the things he like is supposed to be doing. And he's just like, this book, like it shifted everything and it's kind of like almost, I guess like a tipping point for all the changes that happen and kind of the rebellion that occurs. So I think about that, and I think about Natasha Tretheway's book monument that talks about all the different kind of monuments that are around the US, and her thought process was, you know, not to tear those monuments down, but to build a monument beside them, and also to provide context of why this monument is here. So there was a reckoning, you know, like this person was a slaveholder, like this person, you know, is a very clear and devout racist, like, and we have statutes to this person in our country. How do we address that? And so for her, she was like, I don't want to tear them down, leave them up so that we remember our history, but provide context. And so I think that's what I would want for books as well. I think in school, it's tougher because I think for most of us, we grew up and there weren't really things in the way. Like, there wasn't really much in the way for you to go pick up whatever book you wanted to. You could just go grab it. They'd be like, oh, this is a fifth grade book in it, but if you want to check it out, check it out. Thank you, take them a little fifth grade book and go wherever I want to versus now, I think maybe people are more afraid. And also that might have to do with like people not having as much time to talk and process things with their kids. And so I think that's where the school conversations come into play, but I think long-term and for whether or not, you know, when I walk into a Barnes and Noble, as long as they continue to exist, you know, that you can pick what you want and read it, but having been taught the critical thinking skills and to be able to have discussions about these things that you read so that you're not just in a silo and only thinking one way because you'd never talk to anyone else about this thing that you read. So like I'm in the middle and the age matters where they're getting the information matters and then what age you are, I think impacts where I think maybe censorship might have a place, but then I like, my body kind of cramps up. - Like your resistant train. - Correct. Mike. - Yeah, echoing really what Amanda and Vogue have said, I'd say it's kind of a mix. I think I'm more along with Vogue, which is that kind of thing where both, I've got dissonance, I simultaneously am like, yeah, put age restrictions on there. Maybe there's certain things you shouldn't have, but then I'm like, but it is a case by case basis, which is more to like Amanda's point about having the conversation about it. And it's kind of like, I think in schools it is tougher, again, to Vogue's point because it is, I remember there's like a Simpson comic, I read at school, but there's a comic in there about Patti and Selma, like sabotaging a plane so they could smoke in the plane and the smoking light wouldn't come on. And that was just in a comic. And this is like, you know, I'm 30. Well, Amanda's disappeared from home, but I'll continue with the smoking light would go off. And then they were like, oh cool, we can smoke now. And that was the end of the story. It was like, great. You know, we turned off the smoking sign and now we're smoking. And I'm like, this is not appropriate for how old I am, but I, and it hadn't been explained and I just thought it was normal kind of thing. I didn't question it. And then now I'm thinking about it, especially because I did smoke as well when I went into college and things like that for a while. So it's like, well, because I wonder if that's a thing, but I think that very, I think almost like film ratings is how you could almost go about it. But the issue is there are so, so many books, so many. And there's certain context, which is like, you know, for example, like Shakespeare, there's certain very racy things in that. And it's like, how do you, the language is so different? If you can't read it properly, you can't really conceptualize what's happening. And to conceptualize what's happening in a lot of Shakespeare, a lot of the time it takes someone who's a bit more of a mature reader. So it's like, how would you even age rate certain Shakespeare things? And that goes for a certain older text as well. And then when you get to translations and it's like, I, I don't know, the can of worms is too great for me to conceptualize of could even age ratings work. I think if I got ultimate power tomorrow, I think I would just do mature and not mature. And I would think maybe mature, not be in certain school, like young schools. And then it just in a library section, I guess you would kind of, or in a bookstore, you would have like a certain area for it. But the problem is, as soon as you do that, it immediately forbidden fruit syndromes the whole thing. It goes, oh, there's a thing here if you're old enough. You can read this. And if you do that, then it becomes another thing. So yeah, I'm not, I'm not 100% sure. It's a real tough one. Vogue articulates it far better than I did, but it's really that kind of the more I delve into it, the more I'm kind of do agree with both sides. So I don't know. - All right. I love that you mentioned Shakespeare 'cause I'm like, oh, yes, Shakespeare is where I learned the word cuckled, like, no, I know it a bit. - He's responsible for so much of our language, like undeniably so, and it's like, yeah. - So Vogue, what is the value in reading books that might be considered offensive by some? - Well, I know a scholar who specifically reads a lot of books specifically around the Civil War. And I think his thought process is like the Civil War is gonna give you the meat and potatoes of like race relations in the US. And so he had books from people that I was like, ooh, ew. I was like, you read that, you gave that person money and read their book. Like that's gross, I was like unhappy about it. And I love this man. He's like in his 90s, he was like, no, I'm a Civil War scholar. Like I want to learn both sides. I wanna see how these things played out and I wanna understand history. And sometimes you have to look at other people's perspectives to get the full picture of history. And so I think that's the benefit. It's like if you want the full picture, then you might need to read both sides. - What is the value in reading books that might be considered offensive by others? - I think it's really to find out what does offend you in certain respects and why that would be. You know, there's hundreds of valid reasons why someone would feel offended by things. But it's also worth understanding why that is. And then if you come to terms of the fact that you are offended by something and you believe that you are, I don't say valid, but that kind of idea where you are okay with yourself being offended by this thing, you can maybe then look at the person who is causing the offense and why that might be. Are they intentionally doing it? Are they not? Because I think that although they both need to be, although they're both as important and as potentially damaging as each other, there's like intentional offense caused and unintentional offense caused. And those are in a lot of ways, two different things to have to deal with, I think. So I feel like it can help you challenge yourself. But also, some people get offended by things that won't be offended by the same stuff as you. You know, I like a wide variety of music, including death metal and things. So it's like, I know people don't like it and that's fine. But if I'd have listened to everyone around me all the time saying it's awful, it's not music, don't listen to this, I wouldn't have found something that brings me so much joy, you know? It's the same with so many things in life. I'm sure many of us have read a book or watched a film or something of something that someone has told us, no, that's awful, don't bother, it's rubbish. And we've gone actually, I really like this. So there's really, for me with consuming art, the main thing I don't want to consume is something that's boring or bland. I want to consume something that maybe offends me or thrills me or excites me or makes me think. But something that's just boring will not offend anyone. And it's like, maybe you've got to offend some people sometimes. (laughing) - What about you, Amanda? - I think, you know, very similar to what Mike had said, this idea of when you're reading something or experiencing consuming another type of art that potentially offends you, or it's potentially offensive to some people, I think that it begins to stir these questions of like, well, why, like, why is it that this bothers me? And it helps us, I think you evaluate our own perspective, our own opinions, which is important, but then also can lead, again, I think I just keep coming back to this, but can lead to conversations about that, about other people and maybe it's just that, you know, I feel like we are so polarized to use that word that just comes up all the time, but like, we're not having conversations with people who, you know, have profoundly different perspectives and opinions than we do by and large. And if we're not, and these sorts of things can be that good starting off point, right? And even just this idea of like that there are two types of people, you know, and you could have someone that you're so similar to in so many ways, but then you read a book or you see this piece of art and suddenly you're, again, you're seeing it from different perspectives and now you're having this great conversation because you're seeing it in a different way and it's sort of looking at different parts of you and them and I just, I think there's huge value in that. - And we'll stick with you, Amanda. In recent years, there's been a pattern in the themes of the books that get banned. What do you think this pattern says about where we are as a society? - So I think it's, well, multifaceted, but one, I think it's the fact that we're in transition. I think it's reflective of what, you know, sort of the larger culture wars at play. But again, speaking of that transition, I think hope that it's a positive thing. I think the change happens and change needs to happen, but that change is not seamless and easy all the time and that this, a lot of the banned books are a backlash to that. The fear of losing oneself in anxiety of, you know, not seeing yourself reflected in the society of the things that you value, not no longer being valued, all of those sorts of things. And I'll also say that I think this is not just a, like something that is happening among conservatives certainly most of the banned books that you see are being attacked by people on the right. But I think that they left. - Well, what are your thoughts, Fogue? And we'll come back to Amanda if we get her audio back. - Yes, the pattern. I mean, today is the day where I'm like, let's just talk about racism. The racism's so loud and also like homophobia, transphobia, I think makes its way forward when we look at the things that have been banned. And I think really it's like a show of fear. Like we're afraid to let people think for themselves, that we're afraid to allow people to have access to something that has existed literally since the beginning of time, like people who are gay are not new, black people are not new. So it's strange, there's like a suppression. And so I don't know if some people call it equal an opposite reaction, like this is all like we had Barack Obama in the White House for eight years. And so like if the pendulum swung the full other direction, it's like there's a reclaiming or a desire for things to go back to quote unquote the way they were where we didn't have to have as many direct discussions about race and about the cultural differences and land acknowledgments. And that we do, it seems like kids are coming out more. But what it is is just that they are equipped with better language to be able to say, hey, I think I'm attracted to or I'm interested in somebody that maybe you didn't think I would be interested in. There's more language for it. But even my favorite thing about that though, is that there's more language for consent as well. Like when I was in middle school, I didn't have the word consent was not in my back pocket. And I wish it would have been so that I could like directly say what I did and did not want. But I think if we are shielding, we're just gonna deal in the children. If we're shielding them from these very real situations, then we're not equipping them with what they need for the future. And so I think that's also what I love about Margaret's character is often like she's equipped with language and she's equipped with like tools. She's like, mom, I've been practicing this thing for a while. And it's like, look at my girl, like she's equipped. And so don't you want your child to be equipped for the world that they are going to face versus hiding it away. And then they're like, oh, I've never met. I've, I don't have any gay friends. I haven't met anybody who's from a different culture or race or class that I am. What a bland, what a bland life. We're talking about a bland reading, what a bland life to live where everybody you know is exactly the same. And you never learn about the history of our country and other people's countries. As I look at like the list of banned books, I'm like, mouse was so good, but anywho, well, I won't go everywhere. Those are my feelings. - Can we have some audio back? - Yes, I think so. - Okay, the last thing you were talking about the right and then you said and the left. And then you go back. - Yeah, the left. (laughing) - Really quick, I have to say, I love about what you said there about language. And I just kind of quipping people. And that is what books give us and especially kids, right? Like it shows you, it gives you a framework to look at the world, to speak about things that maybe you're not seeing in your day to day life. And that is incredibly, I think it's one of the most important things that books do for people. And one of the things makes being books so dangerous, I guess that, then we're broad kids of this language, this framework, this new age to see and think about things. So I think, as I mentioned, on the left that we sometimes do this self-censorship or there is a culture that encourages that. For example, Tanya, we had read the absolutely true diary of part-time Indian several years ago, the three years ago, I suppose, for banned books. And he, Sherman Alexey, was, you know, had done terrible misconduct against women. And so when the "New York Times" came out with their best books of the 21st century, very recently, I noticed that book was not on there. And I think, you know, it's a marvelous book. And I think that's why I think that it's not on there because of it's misconduct, not because of the quality of the writing. And so when we do that, right, when we say like, we have these like little mental asterisks, right? Like, well, these are the 100 best books by people who we don't find objectionable. And again, I'm not at all trying to say what Sherman Alexey did was okay, but I think, again, then we are, we're not doing our children any favors by that either because everyone is going to have a hero of some sort whom they admire. And then they realize, they learn about that person and they realize that they are not a perfect person, that maybe they did awful things, truly awful things. And then what do you do with that, right? Do you just cast them out and say, well, they're terrible and everything associated with them is terrible. Or do you sit with that sort of cognitive dissonance and say, yeah, what they did was awful and terrible and reprehensible. And maybe I don't want to even support that with my money and my time, but that doesn't change necessarily the value of the work and what they contributed in a creative way. And so I think we're letting our kids sit with that uncomfortability, know that people aren't perfect, know that their heroes will not live up to the way that we framed them. I think it's actually a good thing because that is the unfortunate reality of life. - Yeah, that was worth the wait. Thank you. And I want to stick with you while we have your good audio. - Book bands are only one of the many freedoms that are under attack in our respective countries right now. And more so in the US and the UK, but the UK is also guilty of it. Why is it important that we continue this particular fight with all the other fights that we have? - I think about, you know, our children, kids growing up in places where like books are there only that they're only lifeline. They're only way, you know, to see themselves in the world because otherwise the world is telling them you're not, you're not good for whatever reason. You're not good because of your, you know, your sexual preferences or your gender identity or the color of your skin. And you're not, you're not normal. You're not equal, all of these things. And books are a way for kids to see like, there is a world where I belong. And of course they belong, right? But if we take that out, if we ban these books, you know, they're talking about transgender people, for example, then the people who need that the most, who need to see that they are just as a beautiful and important person in society, like they lose that. And it has devastating, devastating effects. And so I think for that reason, it's just incredibly important that we, that we do, that we have this fight. - What are your thoughts, folks? - I'm like sitting with Amanda's answer and just thinking about it. Because when we talk about specifically like transgender people, like the suicide rates for LGBTQ keros is really high. And that comes from feeling alone and not understood. And so like maybe your parents don't accept you for who you are, but maybe you find this a book that affirms you or at the very least shows you you're not the only person who's on that journey who feels that way, who knows that about themselves. And so sometimes the book is the lifeline for like the counterpoint to loneliness and depression. And so I think about that in terms of yes. Sometimes art, like the writing, someone's writing can save someone's life. And that's enough of a reason to want to continue that fight but to be seen. The number of books I get to buy for my nieces that have little black girls on the cover like makes me so happy. And I'm like, "Look, little black ballerina." Because yeah, growing up maybe I didn't see as many black ballerinas or black doctors. And so like studies have already shown us about representation and why it matters. So like, what are we blocking in that process if you're trying to protect. And when I think about every movie with a kid or like when someone's lying to another character and like, I was trying to protect you. And it's like, well, you should have told me the truth. Like this is the recurring argument conversation. Look, I love that you all know. (laughs) It's the fastest path to like destroying relationships. And so yeah, I think for the sake of honesty and truth and discussion, like we need these things. And yeah, regardless of kind of, there will be ramifications but the better skills we read a book on communication (laughs) then get after it. - Mike. - Yeah, I think my biggest issue when it comes to the idea of banning books is who decides what gets banned. And the truth is, is the majority are not always right, especially not historically. And especially in places like the UK and the US where it's generally a white man in charge. There are so many things that have happened because of a, to very much make it in layman's terms, lack of perspective. In the UK, for example, it was illegal to be homosexual until the '70s, which is madness. My parents were alive during that time. There's a type of slang called pilari. It's a rhyming slang that they use to communicate. So someone would sit down on the bench, someone would sit down next to them. If they said a certain sentence that you just go, "What?" They'd be, okay, they're probably not, you know, queer. And so this whole underground kind of thing developed, you know, even though things were against the law because the majority of people in the UK at that time were at least perceived in that way, were against homosexuality. Alan Turing, you know, he was famous for, I think it's the enigma code. I think he cracked that and they chemically castrated him because he's homosexual. And so it's like, there's all these problems that happen when you have a group of people who think they know best. And I know that's basically colonialism in a nutshell, where they think they know better and they are trying to get rid of someone else's perspective, someone else's culture. Someone else's language. And banning books is just that. It's silencing a voice. When the sort of lower class people learn to read, that's when society really started accelerating. That's when new inventions started to happen. That's when progressive ideas started becoming more commonplace because you could spread information. You could spread perspective. And if all the books got banned, if the people in power banned every book successfully that they wanted to, society wouldn't have progressed anywhere near the amount it would have done. And so much more pain would have been inflicted. And so I just think that a lot of it in one way of looking at it is just who gets to decide what gets banned? And that question leads you to so many pathways when you look at history that I just don't feel like it's an appropriate thing to do in the modern age, especially because the internet exists and banning stuff doesn't really work. It actually just puts a spotlight on things. - Yes. - So let's put the spotlight on today's book. Published in 1970, Are You There God? It's Me Margaret is a middle grade novel that tells the story of 11 year old Margaret Simon, sixth grade year in Farbrook, New Jersey. Margaret grows up without a religious affiliation because of her parents' interfaith marriage. And over the course of the book, she shares her secrets and her spirituality in her personal discourse with God. The New York Times selected this novel as the 1970 Outstanding Book of the Year. In 2022, Scholastic included it on its list of 100 greatest books for kids. And in 2010, when Times Magazine included it in its all time 100 novels written in English since 1923, they said that Bloom turned millions of preteens into readers. She did it by asking the right questions and avoiding Pat easy answers. - Mike, you jumped at the chance to discuss this book. Why is that? - So I think I said at the start slightly, I reveal my hand too quickly, but I watched the film beforehand. The film came out in 2023 in April May in the US and the UK and kind of spread sort of worldwide in 2023. And the film is incredibly faithful to the book. Judy Bloom actually was a producer on it. And she has said in interviews that she actually feels like the film is better than the book. Now, that I think is, yeah, which, and when I read the book and the film, the differences are very slim. There's almost everything is beat for beat. The things I think they've added to certain elements and characters, I think you get a lot more perspective of the parents and things like that. But I think that also the book in itself is important to a whole group of people, especially younger people. And I think they need to go hand in hand in a lot of respects. But that's why I jump at this because the film is one of my favourite films ever. It is my wife, Megan's favourite film of all time. I love people films. I love human dramas that are low stake. The way way back, that's my favourite film of all time. It's got Sam Rockwell in it, who I adore. But it's like, films like A Little Miss Sunshine, that kind of vibe where it's just a clip of someone living their life. And that's what this is, but it's at a crucial moment in a girl becoming a young woman's life. And I really found that I went there and I took, me and Megan took our respective mums. And it was such a great thing because I know there's a little bit, which is gonna bleed onto this, I'm jumping ahead, but it opened up conversations with Megan and my mum's about things. I went to the toilet and came back and they were talking about when they had their first periods and things like that. And it was like, it was something that's really important. I think that this is definitely important for young women to consume because you get that perspective. But I think it's equally, if not more important, for young men to read that or young days. But people who aren't biologically gonna go through this, it's important for them to read it as anyone else. So when I had the opportunity to speak about this, and really the reason, 'cause we've had this book, we got it shortly after the film came out, we were like, we love it so much as by the book, and hadn't read it. And this was a good excuse to see like, what is the difference? I love the film so much. I wanna read it, I wanna experience it in a different way. And because it's a point of view, first person, I don't read a lot of those books. And it's interesting reading something like that because I don't usually connect with them in the same way. But it just feels so important. And Megan and I said, if we could make the film go across and showed in every school, we would. It's like PG, there's nothing in there I feel like anyone should or could get offended by. But the film is just so good that I just want everyone to experience it. So any way to shine a light on the book, and then also obviously because the film exists and I keep waffling on about the film, both of those things are just so important and the more I've looked into it for the research into this conversation, the more it's just this book is so incredibly important. And I think the book in itself is just so, it's like humble, it's really nice. And it's tackled some really important things, but it's not trying to be this giant world ending story. It's the story of just one young woman. And that is as important as a story about the world ending. An individual story is important. And I think that's the beauty of this book. Amanda, why did you choose this book among the options this year? - I had read a couple of Judy Bloom's books when I was younger, Freckle Jews, Tales of the Fourth Grade, Nothing. I think I had read the Pain and the Great One, but I did not read this book. And it felt like I'm aware of the book, right? It's certainly, I think, a book that's part of the popular discourse. And so it was one of those books that you feel like, well, this is a book I missed. I missed reading. And so for that reason, I wanted to read this book. And I very much agree with what Mike said. I think it's thinking about those other books that I had mentioned. They were great for their own thing, but this book is sort of a bit more transcendent. It's not just kind of a fun read. It speaks to you and it makes you think. And it touches you in a way that I think some of the other books that I had read by her, again, which were great, but I don't think that they reached that same level. And this book really did. So I was thrilled to be able to read it and be part of the discussion. - And Vogue, I specifically asked you to join us for this particular book. I won't ask you why you chose it, but I will ask if you have a history with it. Like, did you have a history with it before reading it for the series? - I don't think I read this one for the series. I like quote, like, are you there, God, it's me, Margaret, all the time. Like, are you there, God, it's me, Vogue. Like, it's infectious. It's an excellent title. It's a question I feel like we all like at some point, someone you probably asked, like, are you there, God? Help a player out. So I love the title so much. I had read like the, I was into the Fudge, the Fudge series and Super Fudge. And then there was a TV show for a little while when I was a kid, there was a Super Fudge TV show, which I was all over. And I just, I thought Judy Bloom was really a kid. Like as a kid, I was like, Judy Bloom's clearly a kid. Judy, like, would sit next to me in my class, obviously. It's how good, I felt like she wrote kids. And I was excited that you asked me for this one because you already knew, I was like, look, Tanya. I need, I need soft, joyful things. I have to read soft, joyful things because after out of darkness, I did that. - That was one of the reasons I was like, I want you back, but I don't want you to be afraid. Come back. - It's like, all right, I'm in, I'm in for Judy Bloom. So, and it was relatable. It was, I was surprised at some of the themes and kind of like happy and excited about them. And I just, I love Margaret. I love her. I love her grandma. I love, I love grandma's, you know. So it hit all the good spots. - So what do you think made it polarizing to the point of being banned? - Oh my God. I mean, look, where's my, I have my list? - Band reasons. All right, we've got, we must increase our bust exercises. We've got, we've got Playboy. We've got, you know, kids kind of experimenting with their sexuality and weird ways. Like, I didn't grow up. We never had like intergendered like parties. Like, that was not a thing that I recall attending other than in school. But I remember watching like, even boy meets world, like there's like the spin the bottle and the seven minutes in heaven kind of thing. I never experienced any of that. I don't even know what I would have done. I never had any of those experimentations. But I feel like those, like this could give a kid ideas like, oh, spin the bottle. It's so well described. So I think those things, primarily though, like that everybody's dad had a Playboy, like that it was like, everybody knows, just grab your dad's Playboy. Like the era pre, you know, click that click. And it's in front of your fingers. So I think those reasons. And I also think there might be some antisemitism might be part of the reason why the book was banned. And also this, the primary theme that I loved so much is like, this is about your, this is about your personal relationship with God. And it's not about a specific religion and that the child was encouraged to figure out what she wanted and then like that soft little bit of, oh, first male teacher. And I actually was curious for you all and like, not taking over your podcast. But I wanna know when you guys had your first male teacher, I think mine was in fifth grade, but I'm curious when you all had your first male teacher, 'cause they kind of made a big deal about it in the book. And I was like, huh, was it super weird in the 70s for a man to be a teacher? And so it was, it's cutting edge, if you will, or it was pushing up against the envelope for so many reasons. And I loved that. I loved being able to walk through these conflicts and see how they kind of got resolved. - Yeah, I don't remember that. That's like, I don't, there are so many teachers that I just don't even remember. I was trying to walk back through it. And it's like, you know, I don't remember, I remember one elementary, actually I remember two elementary school teachers and I know they were both female, but I couldn't remember the names. Like I just have a very vague image of them and the rest I don't recall. - School wasn't your life? (laughs) - School was my church. (laughs) - I tended to feel like the instructors were not giving me enough in elementary pages. But go, I was very self-taught. I enjoyed learning and reading and doing things at home. And then I'd get to class and it'd be like, oh, we're not teaching that yet. - Well, I'll just be over here waiting for everybody else, you know. - Oh. - What about you Amanda? Just to answer this question really fast, do you remember your first male teacher? - Yeah, I had a, in first grade, I had a male teacher he taught half of the day. He was actually the music teacher, but my, the first grade teacher went, I'm attorney and I leave. And so he, and another teacher split, he done morning and another teacher taught in the afternoon. Mr. Corett, what's his name? - Mm-hmm. - Nice. - I remember I had a male principal, but I don't remember having a male teacher. Like I just, I don't remember my teachers in those grades. And then, you know, you get to six, seven, like you have a mix. You have classes, you have a mix. What about you Mike? I don't know if it's the same over there. - I didn't have any male teachers in primary school. So that was from up to the age of, when you get to sort of 10, 11 years old, then you move on to secondary school in the UK. And then it's, yeah, mix different teacher for a different subject. So yeah, I was just thinking, you know, 'cause I don't, again, primary school was a Catholic school. The only male in the whole school I can think of, there's the janitor and there's one dinner man. There were dinner ladies and dinner men, but he was, he's actually the dinner ladies and dinner men. - Sorry Mike, by music teacher in elementary school was definitely man and he was 100% queer. (laughing) And I loved him. Like he was, he was wonderful. - Yeah, I don't think mine was just the one guy. I don't know if that was though distorted because it was a Catholic school. I don't know because of the more traditional views and maybe thinking it's the winnish teacher, I don't know. - I just don't remember it being sensational. You know, it wasn't like, my teacher is male. I don't have that memory of thinking that was something special. - I think in the 70s, it was the same, you know, people, oh, a male nurse, like you got to put male on it. Like Amanda knows. (laughing) And that's been now still a little bit. I think the male nurse and being like a male nanny or being like a babysitter and being male, I think there's a lot of those things where you're like, "Really?" Why don't you, you know, the society in a lot of ways has to help head tilt when you say it. - Yeah, which is a shame. 'Cause men can care give well. So we should let them do it and not be like, what do you do it over there, if she didn't? (laughing) It's like a shame. - Back to this book, Amanda, what did you think made it polarizing to the plane of being banned? - So there was actually a part that's like four lines, I'm gonna read it when I got to it and I was like, "Oh, this is it, this is the moment." She says, "I've been looking for you, God. "I looked for you in the temple. "I looked for you in church. "And today I looked for you when I wanted to confess "what you weren't there. "I didn't feel you at all. "And I could just feel all of the religious fanatics "being like, of course you can find God in church. "What does sac religious think to say?" And so I thought that's, to me, that was the moment, that it is this idea of maybe God isn't in our religious institutions the way that, and it's, I mean, it's just her. She's just thinking, I don't know, I don't know that this is necessarily Judy Bloom's critique about organized religion, but I could see how people might feel that as an attack on organized religion. So, and I do agree, again, with some of the other things that Bill had mentioned, like talking about menstruation, I think about this ridiculous thing that's come up about the tampons, tampon tin, and how Tim Walz put sanitary products in bathrooms for girls that didn't have access, right? And other girls and people who need those products and how it's like become this firestorm, right? And so, apparently, menstruation is also a touchy issue, I don't know, but I thought, in particular, I felt it was this potential critique on organized religion. Mike? - You know, I struggled at first, that clearly comes from, you know, me questioning religion from a young age. So when I have people questioning religion, I'm like, yeah, this is normal. So, until I was trying to think, I looked it up, so I kind of cheated, I already kind of knew why, but like, I was trying to wrap my head around when I read the book, 'cause I'd seen the film again, and I was like, nothing in the film, it's done in a pretty much equally tasteful way. There's one conversation in this, I don't want to spoil the film, even that they're very, very similar, but there's one conversation in this that there's a part, which is... - We go into this knowing there are spoilers, like... - Yeah, that's fine, so there's a part near the end when the Christian grandparents come in, and then a base key kind of seemingly, it feels like the grandpa is yelling at Margaret and saying about how like, you can only feel God in this way, you can only feel God in that way, kind of stuff. So it's really his argument against the quote that Amanda read out, that kind of idea, and he was like, you're born as a Christian as well, your mum was one, and therefore you're one, that thing. That was the only part I read, and I was like, don't like that, I've met people who are like that. So that's not on Judy Bloom, that's actually very accurate, it's like, yeah, they wouldn't say it, but there's a lot of people who think, you're born this way, and therefore that's a certain thing about you that I'm gonna judge you for forever. You know, there's lots of that going on, what could that be about? I don't know, moving on. It's one of those where I just think anyone who gets offended by this book needs to grow up. It's just, I read it, and I was like, this is such an innocent, nice, pleasant book, and I finished it, I was like, that was just a joy, like really nice seeing really what the inner monologue of a 11 to 12 year old woman could be. Like, and I just found it really nice and fun, and I was like, I wanna finish it. I was like, oh yeah, this is a band books conversation. I was like, this is, I know that normally in your conversations, Tonya, you normally have one or two books, I think Charlotte's Webber's last year's in the year before that was like Harry Potter, where it's kind of like, here's a book that you wouldn't expect to be banned because it's either so widespread or so perceived as inoffensive. So for me, I think it must be just bouncing off what Amanda and Vogue said, is just the religious questioning, and the accepting of that, I think religious, especially fundamentalist would have an issue with, a friend of mine, their family, Jehovah's Witness, and when my friends started to question their own religion, they got thrown out their house when they were like 16. They sent a day or two later, they got back in and they stayed with a friend and stuff like that, but that was deeply traumatic. And that's literally, that's in the UK, down the road from me, I've met the parents, they don't seem like bad people, you know, whatever bad means, but like you then delve deeper into that and the certain restrictions that their sect of their religion brings. And I can see how a book like this saying, "Hey, maybe there's not one way to do it." That could be for a lot of people, I think it's the fear of the unknown, which causes almost all problems in this world, which is I don't understand that, or I don't like it. And instead of trying to understand or trying to work out what others like it, I think it should go away forever. And that's a huge problem with pretty much almost all the bad books I've seen that you guys have tackled so far across the episodes, is just like, usually it's fear is the reason, you know, why would you set a book on fire? You'd probably scared of it. So I think that's agreeing with those guys' points. - So according to Politico.com, it says that almost as soon as Margaret was published, it was banned in certain corners. Bloom has said that her own children's elementary school principal wouldn't shelve it in the school library because it mentioned menstruation. In the 1980s, conservative warriors, it was Jerry Falwell and someone named Phyllis Schloffle, I don't know who that is, made Margaret and other Bloom books a target of their ire, including a pamphlet titled, "How to read your books, "How to read your schools and libraries of Judy Bloom books." And then the Washington Post said that Margaret was banned several times in the 1980s and landed on the ALA's list of the 100 most banned books in the 1990s and the 2000s. The bans weren't imposed because the book was regarded as sexually offensive, profane and immoral, and built around sex and anti-Christian behaviors. And in that same article, it mentions that Bloom told the BBC that people must fight the bans because even if they don't let them read books, their bodies are still going to change and their feelings about their bodies are going to change and you can't control that. They have to be able to read to question. So what are your thoughts on the reason it was banned, Amanda? - I mean, I feel like I should not be surprised, but like, it's so, menstruation is just, it is a biological function, you know? And also, thinking about my own, this book made me think a lot about myself at that age. And while it was certainly something that was talked about in a scientific way, my parents are both scientists, and you have school where you're learning like, "Oh, look, this is where the line at the uterus." The uterus is schloft off, right? And this happens every month, blah, blah, blah, blah, blah, blah, blah, blah, relation, right? Like, I knew all of those pieces, but like, I did not know, you don't know what it feels like. You don't know. I asked this question in class, you know, they did the whole thing that they did in this book where they separate the boys and the girls. We had this opportunity to ask questions. Well, I had no sense. Again, I could tell you what was happening to the lining of the uterus, but I had no sense what the period was actually like. And it was not something that my girlfriends and I talked about unlike in the book. I love that they talked about that, right? It was like this thing that you were going through, this shameful thing that you're going through alone. And it felt very lonely, it felt very frightening. And so to hear like, to hear that being the reason that it was banned for so long, it just, it blows my mind. It blows my mind. And I think it, you know, I just think it speaks to this, this, I don't know, this steeped misogyny where like anything that has to do with the female body is less than and gross and shameful. And I don't know, I hate that. Mike. - Yeah, it's one of those where I think the religious element was a part of it, but obviously is what you've said there is that the mention of menstruation was quite a lot. And I think, I think what a lot of that comes from is historically, a lot of men have tried to prevent women from becoming literate and reading and knowing anything. Because, you know, if you have someone who doesn't know anything, you have a certain degree of power over them. They depend on you, if they can't read and they can't work and they can't do all these things. And you feel that with, you can only be a certain thing in a lot of cases, like you can only be a housewife and a mum and you don't allow them to be educated in other ways. And you also make them feel isolated that their problem is only theirs. It prevents freedom, it really prevents people flourishing. And what it does is it unbalances the power dynamic in a lot of relationships. And I just think it's, you can, there's certain red flags about men that I think you can, are quite easy to find, some are more subtle. But I think having a real problem with, you know, periods and women menstruating, aside from having a physical reaction to seeing blood, which some people have, aside from that one, if you meet a man or anyone who's like, you know, against doesn't want to speak about menstruation or things like that, obviously there's a time and a place, you know, not necessarily around the dinner table, but a man who's genuinely like disgusted by it and won't talk about it and what doesn't even want to know, like that kind of thing, that's like a red flag for me. 'Cause I'm like, either you're acting like a tiny, young little boy, or it's something much worse. And it's like, neither of those things is really anything that someone should be. And it's something so basic, it's something so simple. And it's like, literally, it's one of the steps in how life is made, how can you have a problem with that? I don't, I'm conceptualizing of that. And again, it's that thing of someone seeing that, thinking about, you know, blood coming out of a vagina and then going, that to me is gross. And therefore, that's bad. And therefore, no one should ever talk about it or in any way, shape or form. And unfortunately, it's a weird parallel I've only just made, but that's an argument that's a terrible one and for straight to me to no end, when people are against homosexuality. Oh, seeing those two people kiss, that grosses me out. It's not about you, none of that is. And it's the same with this, I think, is that, oh, grosses me out, no, you know, and I hate that mentality. And I think that's what a lot of this book represents is normalizing things that are normal, but for some unknown reason, there are stigmas around it, you know? And I think that's why. - Well, yeah. - So a lot of nodding going on during what Mike was saying. - Yeah, I think both of you, you know, hit the nail on the head. And I think it's the slope, I guess. And the direction is like, you know, even when they were coming up with the COVID vaccine, they didn't test it on women who were menstruating and didn't talk to us about like how that vaccine would impact people's cycles. And so it's like, you keep leaving out a major component of how many of our bodies work. And we leave that information out, like you're causing harm. And so that's deeply frustrating. Like I had a group in a household with only women. And so there was never anybody who's like, oh, don't talk about your period. It was like, no, it's a period, it happens. I was well read by the time mine came, I was like, all right, cool. Calendar, you know, it was marking it up. And I was like, I already know how this is gonna go. This is the shadow of my uterine lining. Like, but I don't want to have no kids just 'cause I'm 13 and bleeding. Like I don't want that. And that's the thing, it didn't even go into sex, you know, it just stayed in a period. I think that there was questions and interest around sexuality that was like, God, it feels like this, you know, Nancy wants to know so much about, she's practicing kissing her hand and those elements and having the book of boys that you're crushing on. And so it almost felt like Nancy felt like she was this like forceful shepherd of everyone's sexuality in that girl group and that friend group. And I was just like, I don't really like this. I wasn't happy with Nancy, but I think for me, like that's a conversation starter with my kid to be like, if you have a friend who's pushing you in this direction, you know, you might need to have some questions. And how was it Laura? Is it Laura or Lauren? But the girl who everyone was saying was fast basically. I was like, oh, she went behind the A&P and was like doing, we don't even know what with those two boys. And so how the cruelty of rumors and how they spread. Like, those are the lessons that I loved that I got to see in the book. And so it is frustrating to see that, oh, you just don't want to talk about periods. And it's something that impacts numerous human beings that you love. We had to do better. Yeah, and I don't think the characters in the book even knew what she was accused of doing behind the A&P. Yet it grew into this thing that caused something very ugly. And then she realizes, wait, I don't even, I don't know why I even believe this. The source of this rumor lied to me about this. And then she's finding lie, lie, lie. And I didn't necessarily like that character, but she felt real. She felt very authentic. I think it was a masterful book, even though it is not written to be some great work of literary art, it still is. Because it's so accurate, it's so authentic and it's just charming. And I thought I had not read it. Like, I thought that I was like Amanda and had not read it. It's like, let me add this Judy Bloom book. And when I started, it's like, oh, I know this story. Yes, I was just in it, you know? So vote. - I think the funniest part is the fact that like her proof of God is that her period comes. - Right. - Oh God, I knew you were there. I think like, girl, you better stop playing. Like now we pray, like half must pray our periods away. And she's just like, I just wanna get it. But the line, I just wanna be normal. - Yes. - Ah. - Yes. And even when she's questioning God, she's talking to him, like, and I don't believe in you, God. You know, like, why are you talking to him? (laughs) No. Who are you saying this to if you don't believe? So yeah, just all of that. And oh, I knew I can't imagine anyone wanting that sensation. Like, you want that early? But because it was their culture and yes, they wanted to be normal. Like it was all very believable. - Yeah. - But I wanna start with you for this vote. What are the reasons that people should read? Are you there, God? It's me, Margaret. What are the conversations that can start? I know that we've covered a lot of it in this, but what are your final words for why this is a book that people should read? - I think it's good for people who are kind of wrestling, wrestling with their faith and like what kind of religion they want to go towards. I think seeing like Catholicism through a child that like, oh, we had to stand up a lot. (laughs) Like, yes, like it's an encouragement to go out into the world and like, yeah, see how other people practice their faith. And like, I think that her perspective was so like beautiful in that way. You know, if you are a person who has like, church like harm, if you grew up and you have family that you no longer speak to, that you're estranged from because of religion, then it might be a book that might do some healing for you. I think that, gosh, there's so much. I think if you do some good laughs and thinking about even the parents that the mom is an artist and the dad works in insurance. And so I think if you just kind of want something that's like slightly weird Americana wholesome and I was surprised to catch like the components of like Jewish culture there, but like all the different things and the ways that people were expected to act. I think it's like the snapshot of this moment and thinking about how I envision as like a native Californian. Like imagine like, this is what New York was like. I can know why would you move? Why are we moving to New Jersey? You know, I think those are the things that kind of make it so warm. But I think for sure those conversations about around religion and family. - Mike. - I think that the book is very unassuming. That was the word I think I was reaching for before. It's just so, is it mirrors perfectly what the mind of a sort of pre-teen going into puberty can be like? You know, I can't speak for someone who grew up, who went through female puberty, but I went through male puberty. And even with certain aspects of that, there is still a lot of locker room talk, shall we call it? You know, not misogynistic, dangerous stuff, just like boys talking about their bodies. It didn't happen as much. It more so happened, I think, you know, later. Because I think generally men do go through that a bit a few years later than women generally do. But like, I remember there were certain conversations happening about that. And this weird pseudo-pressure. When no one, maybe there's one little instigate on the group who's trying to push everyone's buttons. I've seen Nancy was kind of it in this. But it's kind of like, no one else seemed to care, but everyone else clearly cares. So I have to care because everyone else cares. And there's just so many little lessons in this book that just, they work whether or not you are a child, a teenager, any age, any demographic. You know, I noticed, I'm fairly certain that they, although they mention religion, they don't mention anyone's race. And so I think, and this book has been translated into so many different languages. I think it's like 70 or 80 languages or something. Or maybe there's so many countries it's been to. You know, it's one of the most spread across books. And I think the reason it transcends is because there is the eye perspective, but also the descriptions of people can fit to other people you've met. You know, an example I'll use, and I know the author is terrible, so I'm sorry. But in Harry Potter, let's think about the films. When you had Umbridge as a character, people disliked Umbridge more than Voldemort. Because you can't hate, you hate Voldemort 'cause Evan hates Voldemort, he's just pure evil, easy. Umbridge is a person we've all met. She is someone that has made your life terrible because they're on a power trip or because they've just taken a disliking to you. Or for any reason, we've all met an Umbridge. So for us, we hated her. Voldemort, whatever, Umbridge, everyone hates them. And I think what this book does is without this hateful thing that I'm exuding about Umbridge. It's about the dynamics of friendship, the dynamics of family, and the dynamics of what religion can do, and what people's beliefs, the strain can put on families. And in this, you could put this through as a queer lens. You could just say that in this book, you could argue, although there's the stuff with Moose and Philip Leroy, there's stuff with Laura, I think. You could have the lens and the perspective going, "Maybe she's inclined, she often calls her beautiful, "she's always staring at her." And that kind of element. And you go, "If you looked at this from a queer lens, "it still works." So if you're a young, or any queer person, and you read this, you can kind of feel seen in a way, even if that wasn't necessarily maybe the primary message, I find. So I think it just translates language, it translates culture, it translates really even through biology and gender. It's just something, it's an experience of growing up. And I'm a big sucker for coming of age stories. And I just think this opens up so many great conversations, especially across genders, because there's still a weird stigma about talking about puberty and things across genders. It's an odd thing, but Megan and I, we had great conversations. She said about when one of her friends got there a period, then she was thinking, "When am I gonna get it?" And there were these little thoughts. And I must increase my busting. Megan's mum, after we saw the cinema, she said she remembers people doing that at the time. It was a legitimate thing that she remembers and stuff. So there's fun things in it that just work so well. It's so good. And I just think it's so wholesome. And if you enjoy this, I think people should also watch the film. It's really great. It's Rachel McAdams and Kathy Bates, incredible people. And I think that the book is more insular of Margaret's experience. And I think what the film does expertly is it widens her sort of blinkers a little bit. And you actually get to see it more from a third person perspective of all of them. All of the characters have a lot more to them, especially the parents. 'Cause in this, I think the parents, you see what they do, and there's a little bit of dialogue, but it's so not about them. She's seeing it from a child's perspective. She's under their chin is looking down in a way. And in the film, I think it shows you the other people, including the grandma and stuff. So I really like that element. And it's just family dynamics are complicated. So feeling seen when any of yours are on screen or in a book is just, it helps deal with some of that. So I just appreciate this book and this adaptation in all the right ways. - Well, you've convinced me to watch the movie. I will definitely give it a try. - Now we're gonna have a movie night. - Do it. - They can always have people re-watch that film. - That's the best grandma. - Yeah, Kathy Bates. - Yeah, as she is, she's one of the best characters. She's just so good in it. And there's a lot more humor I'd say in the film. I won't say anything else about it, but there's humor without taking away from the really important themes. And I think the questions we will discuss about this are somewhat amplified in the film, which I really like. - So Amanda, bring us home. What are the reasons for you to read this book? What are the conversations that can start? - Well, you know, I think you really touched on it just right there and read the book because it does have all these wonderful conversations that it can start. And it is, as the others have said, it's very tender. It does have this sort of just incredible, relatable feeling. Whether, and again, I mentioned my experience was so different from hers, from Margaret's, but like at the same time, it was so relatable. And I was thinking back and I was almost in tears reading the book, like it just, it is very touching in so many ways. And I was just recently listening to an NPR article they talked about in the United States how interfaith marriages are so much more common now. I think they said almost like one in five people are in an interfaith relationship. And so her situation in that way, I think, is becoming even more something that kids can see themselves in. And that's really important because, you know, I think Vogue hit on it, this idea of like wanting to be normal and wanting to belong. Like she really brings that through in this book. And that is something that transcends all the things, whatever, you know, your gender or your race or all these things. There's this feeling of wanting to belong. And I think that's what makes this book so wonderful. - And I, can I add? - Yes. - That when we get to the end, you know, that Margaret has no fear about buying like pads at the store is like, I don't care that it's a male cashier puts it up on the thing and it's like, you know, I have my, we need these products. And it took me, I think I was in my twenties when I finally was like at a target and was like not trying to hide it underneath things. And her shifting, apologizing to Moose for assuming things about his character, apologizing to the other girl as well that she came into her own, like, so instead of just being a follower, she crosses that road and says, what kind of young woman, what kind of, you know, what kind of person do I want to be is like my favorite thing where I'm like, yes, take over the world Margaret. - If I can add to that funnily enough, is that I agree completely. And I think that the whole book she's constantly saying mental notes of what she does and doesn't want to be, when she knows about Nancy, she's like, I don't want to be the kind of person who lies to friends. When her, she's like, I like my grandma because she makes effort with me. I don't like this element of this character because they don't do this thing. And you kind of, without realizing to the end, you're like, she's almost not like taking off traits. And by the end, she's like, oh, this is what the kind of person I want to be and this is where I can be from there. And I think there's a line which is one of my favorite, the things that made me chuckle. And it's just a tiny part of a line, it just says, and that's when I decided not to be a model. And I was like, just, I love that 'cause that's when you're like, when you're a kid, you're like, you know what, I'm not, you know, I'm not gonna be an astro, actually. That's not what something we're gonna do is like, I just love the simplicity of it. And that's the beauty of this book in a lot of ways. - And there are no perfect characters in it. Like she loves her grandma so much, but she's like, this is a part of my grandma that I maybe don't appreciate. She's still my grandmother, you know, she's still like my favorite person. She's one of my best friends. However, I don't like this element of her. - And it doesn't try to tie everything up, which I also like, it is, you know, like it leaves a lot of things in question. We don't know what her relationship is gonna be like, with Lauren, Lauren Laura and, you know, even her maternal grandparents, like you don't know that. And I like that we're even trying to solve everything. - She hasn't figured it all out at 12, amazingly enough. - Yes. - You can see she's still growing and learning and open to developing. And that's where we should all be no matter what our age. - Yeah. - Yeah, it was such a smooth ending where I was like, we're just gonna end with, I knew you were there, God, with the period. - Yeah. - And I was like, but it ended with a period. - Yeah. - Yeah. - And I fell off, I folded and I was like, no, this is the story. Like it's, I mean, Judy Bloom is the shit. And so like, it's just, it's a perfect capsule of here's this moment in time. Like you said, the beginning, Mike, like it's about a very specific time in this young girl's life. And the way that time passes. I mean, like, you could study this about how to really stay focused on your story and hold fast to your themes, but still give your reader a certain amount of satisfaction. Yeah, you could teach a class. - Yeah. (laughing) - Well, thank you all for starting off the series with such an awesome conversation. - Thank you. - Yeah, thank you. - And a pleasure. - Vogue, tell everyone where they can find you and support your work. - Let's see, if you're on my website, it's just vogue316.com. And then you can also-- - Sorry, I just realized you two have the same birthday. You and Mike. - What? (laughing) So rare. - So I apologize for interrupting. I just had that whole-- - More than 365 chance, you know? Pretty rare. (laughing) But it is fun. It's right to meet someone. - We'll say it again for the audio listeners who are like, I was writing that down and she started speaking, root host. - Yes, yes. My website is vogue316.com. You can also find me on Instagram and it's vogueR316. I try to be consistent. So the Instagram is where I live and love. And then my website, you can contact me directly. - And our other March, baby, Mike. (laughing) - Yes, so find me @genuinechitschat on all the social media places. If you just Google, genuine chit chat will come up. There's a couple of, I've got WordPress site loosely and things like that. There's a YouTube channel as well. I've been doing the podcast for seven years. Interview style podcasts have a different personal approach every week. And I've had Tanya on, yes, six times at least. We've done loads of collaborations on comics in motion, which is another place that I distribute a lot of podcasts on. We spoke about low key. We spoke about a lot of the weekly stuff. When the Star Wars shows come out in live action often I have Tanya on and we chat about that. So really search Tanya. - We talked about religion too. - We did, yeah, so episode 188 of genuine chit chat. Myself, Tanya and Beasy spoke about religion as a whole for about two hours, I think nearly around a half. So if you want a starting point and you've not heard of me before, just genuine chit chat and Tanya tod on YouTube or any podcast player. And that'll start you off springload you into my world really 'cause that's, I'm just a podcast that you guys are far more accomplished. And like, you know, creating all this stuff. And I'm like, I just like having conversations with people. And that's how I met Tanya and you lovely people as well. So, you know, thanks for that. And thanks for having me on Tanya, I appreciate it. - And Amanda. - Like Vogue, you can contact me at my website, amandascanidore.com. And I am also on Instagram @amandascanidore.com. And I look, you know, Mike don't downplay the conversations because that's, I think that's the crux of so much. - Really? Like would I have this series if it weren't for meeting you and having a conversation with you, but I have ever become a podcaster. If I hadn't met you and had a conversation with you, would I have met the comics in motion network if it hadn't been for you? Which means I wouldn't be on them on. - Mm. - I think you've probably still done a podcast 'cause you're an unstoppable force, but you probably wouldn't have met the other people as well because I wouldn't have had your guidance. - Oh, that's very kind, I feel humbled. Amanda, could you just spell your surname? Just, I know it's been the show notes so I'll make sure Tanya puts in there. - But just so. - Yeah, thank you, yes. (laughs) That comment of the last name. It's skin and door, S-K-E-N-A-N-D-O-R-E. - Thank you. - Well, thank you all again for today's conversation. Thank you listeners. If you enjoyed what you heard, please like, comment and share. Thank you for listening more importantly. Thank you for reading. [BLANK_AUDIO]