Make More Pie

Michael Powell and the Permeability Between Worlds

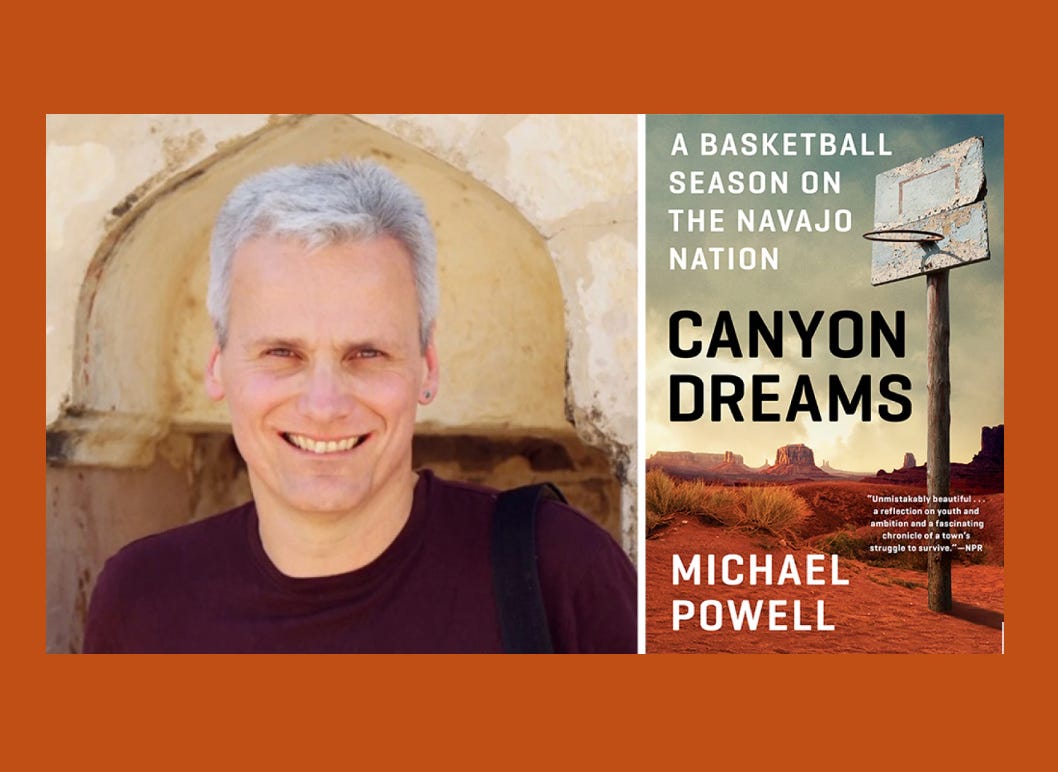

[ Music ] >> Good morning, Smoke 'em. If you got 'em, listeners, it is I, Nancy Wallomon here, not with my better half-serve upload today, but with one of my favorite journalists, and I'm sure yours too. Michael Powell, who I have written a little introduction for, so Michael, if you will humor me, I'm going to tell my guests all about you. Okay, so Michael Powell worked at the Washington Post before joining the New York Times in 2006. Where? For six years, he wrote the Sports of the Times column, as well as covering New York City, national politics and culture. From 2020 to 2023, he wrote a series of pieces about DEI, about protests and accusations of white supremacy that sparked controversy in some quarters and made others, including yours truly, feel less crazy. In July, 2023, Michael, who I think is one of the best journalists writing today, became a staff member at The Atlantic, where he continues to write about politics and culture, including what it was like at the DNC in Chicago, where he and I ran into each other at one of the explosive protests that wasn't. He's also the author of the 2019 book Canyon Dreams, a basketball season on the Navajo Nation, which will be released as the feature film "Res Ball", co-produced by LeBron James and co-written by Sterling Harjo, the creator of "Res invasion dogs", which I know quite a bit about. Michael, welcome to "Smoke 'em If You Got 'em". Thank you, my pleasure to be here. What did I get wrong? Nothing, nothing, all correct. So Michael, what did you, you wrote a little bit about the protests for The Atlantic? Tell me your sense, because I'm kind of noodling on a very late piece right now about what I saw. Tell me what you thought about them. Well, I mean, it was just this kind of, I thought, like a great, from the point of view of the protesters, a great letdown, right? I mean, there had been talk, including in much of the media. I don't blame the media. You know, it's going to be Chicago 68. There's going to be 70,000, 100,000 people. And like, I got off the, I was going to say the subway, but it's the elevator, the L in Chicago. And like, you know, I looked out at this park, and it was like there were some clumps of people. And, you know, maybe three, maybe, I mean, if I were to be very, you know, friendly to them, 5,000? I mean, it was just, it was fascinating to me how, yeah, I mean, how few there were. And also, you know, I mean, a fair number of those, not to say all, but like a fair number, we're definitely of the kind of sectarian left, right? I mean, you know, Trotskyites, Maoists, this, that. So I don't know, just it was not what I had expected. Yeah, and I guess it speaks to, I guess, like it raises the question, you know, kind of, I mean, there's been this assumption, I think particularly among kind of progressive press, the well, this is going to be, you know, this is a, this is a problem for Biden or Harris or whatever, because you've got this great swell of people. And I don't know, I mean, there wasn't any great swell in Chicago. There was not, it was, it was pretty deflated. And I, as I, you know, it was sort of built as this, you know, it was going to be the big, like the final firework of the night, right? You know, we can go through this all season. And it was like one of those dud fireworks. And I'm like you and I think most people that wrote about it with a sense of perspective were trying to be like really generous. Like, well, I was told of 200,000 and like maybe if I'm being really generous, it was 3000. And I think part of that is that they tried very, very hard to make it like, it was the no surprise, surprise party. Like, okay, you're going to be dressed like this and we're going to say this here. And this is, and it was just, it was just a dud. It felt like, like a, like college orientation. And I don't think that that's even though like I'm not a super fan of a lot of destruction. And I've seen a lot of it covering the protests in Portland. Sure. There's always something to be said for when you defang the, and over orchestrate a protest. Like, it just doesn't have an impact. Yeah, that's interesting. That's, yeah, I think that's interesting. And it's also, you know, I was thinking about it. I mean, look, I mean, clearly there's was, you know, a certain number, particularly younger Muslim Americans are very, you know, worked up on Israel and Gaza. But I mean, this is only like four and a half, five hours from Dearborn, Michigan in Chicago. I mean, and it was just striking. Like, in other words, it should, and there's all kinds of, as we know, all kinds of universities around Chicago. And it just was, yeah, it was interesting. I mean, it just, I, you know, I don't quite know what to make of it. It's also kind of interesting that so far this university year, we've not seen, you know, kind of that that pitch that we had seen last April and May. And I don't, right, I'm like bigger on questions right now than answers. I don't know quite what that's about. I think there is some protest fatigue. I think it is because every protest is, I've called this in my writing before. I've called them like rage calories. You need something that's going to sustain that, that rage and that level of, for lack of a better word, passion and energy. And I think there has to be something to it when you are a marcher and you, you know, from October 8th through, you know, the end of the school year when you're still in school and you don't have to like find a place to live and your dorm is paid for and whatever, you can go out and shout, you know, free, free Palestine or, you know, killer Kamala or whatever. But when you've done that several hundred or a thousand times and actually nothing changes, I think, I don't know if it's a sense of that they aren't, that they, they rethink it and say, like, wow, maybe we're really not getting here with this methodology or you just become bored and start looking for the next thing to enliven you and drive you out into the streets. So maybe that's why we haven't seen much this school year. That might be. And I also got thinking during that demonstration because right, there was all the genocide, Joe, killer Kamala and like, for better or worse, I mean, most liberal, you know, liberal-leaning Americans have worked themselves, you know, torqued themselves into a frenzy about Trump. And I think this, so this notion that you're going to, you know, that you're going to say killer Kamala and like, I just think there's a very limited kind of audience for that, that kind of rage, particularly right now. I mean, I think a lot of people look forward and like, you know, let's get past, at the very least, let's get past election day. I think you're absolutely right with this sort of the overblown rhetoric. I heard a young woman from the stage, I think it was on the second day of the second protest. And she said that, you know, Kamala Harris was directly responsible for murdering Palestinian babies. And the crowd was kind of like, yeah, like they know that this isn't actually true. And I think that they also know, and I wonder if this is what is partly deflating, you know, the day after we saw whether it was 3000 or 5000, March on the DNC 2024 put out a press release saying there had been 20,000 people there. I mean, I think people can smell that it's just not actually true. And I think that might have something to do with the deflation too. Yeah, no, I think you're right, right. I mean, everybody, you know, the numbers game always happens with demonstrators demonstrations, but that was a particularly, there weren't 20 grand, there weren't 20,000 people. No, we're not. So speaking of Trump, you were at the New York Times when Trump, you know, got on to the main stage as a New Yorker. You and I are both New Yorkers, both grew up in New York City. You know, Trump has always been a figure in our lives. He's been this, you know, gaudy guy who was kind of entertaining and like, you didn't really have to think about that much because he was just another kind of New York City character and all of a sudden in 2015. Oh my God. Like, by the way, as a New Yorker, not just as an American, as a New Yorker. How did you feel about Trump as the nominee in 2015? Oh, I thought it was a joke, right? I mean, I thought when he ran, I mean, he's like PT Barnum. I mean, you know, he's like low rent PT Barnum. I mean, it's just, yeah. I mean, I covered, you know, like I worked a long time ago at New York, New State, a tabloid and stuff, and I mean, you know, I mean, he was just, he wasn't even remotely in the highest echelon of real estate developers in New York. He was kind of this, you know, this swaggering tabloid guy, he kind of cut, you know, forever declared bankruptcy, forever let banks, you know, holding the bag. And I mean, he was kind of entertaining, but he could also be pretty gross. And like the idea that of all, of all the people to come out of New York that he would have, you know, captured it was just astonishing to me. Yeah. It was. I did not see you coming. No. And I mean, at first you like, there's no way. And then you realize I was not a person who watched the apprentice. And I did not realize the sort of hold he had on a large part of the American imagination or a large number. Of people and well, there we go. So I also have seen, as I'm sure you've covered it, that he had a unique ability to drive people out of their minds. I mean, he was like not just a chaos agent. He was almost like a some sort of serum that they shot into people's emotional bloodstream and he made people crazy. And I think that that had a lot to do with the scrapping we've had against each other on the many sides or two sides or whatever you want to call it in terms of the culture wars. And I'm thinking and thinking that whatever serum that was that was shot into the national bloodstream is sort of we've sort of developed antibodies against it. So maybe it's falling down, but you really were covering this stuff like from inside the New York Times. And I'd love to talk a little bit about that, like what that was like from the way you write, which to me is, you know, very thoughtful and very measured and taking on like the absolute third real issues when things are insane. How was that like to cover that from inside the New York Times and during this era? Um, it was a bit of a trip. I mean, it was funny. I'd been doing, you know, I had a sports column, which I had never covered sports before, but I wrote a sports column for like four years and I thought like, okay, I'm like, I had a great time. I'm tired of this. I want to get back. There is this sense that like there's this, you know, roiling, you know, cultural and political wars going on. I wanted to get back into it, talked with an editor, um, top editor, Carolyn Ryan. We both had this sense that there were too many things that the Times wasn't either wasn't writing about or was, I mean, I hate these words. I hate these words, like, you know, correct or whatever, but there were things that people were just too nervous about writing about, you know, just in a straightforward way. Um, so I thought, okay, let me do that. Now, in the time between making that decision and doing it, COVID hit and which kind of was like an accelerant on all of that stuff. Um, and it's funny because like, I remember when COVID first hit, somebody tweeted and frankly, I might well have done the same and said, well, don't the, don't the identity wars seem distant now like we've got this great existential thing that's killing millions of people. And I thought, yeah, like there was a moment where I felt like maybe I shouldn't have done, you know, shouldn't be thinking about doing this beat. And then of course, you realize, no, it just, as I say, was like an accelerant, right? Yep, yep. But I will say like, I mean, I'd love to say like, you know, I was like infinitely courageous and all these people, like, I got a lot of support from this editor, Carolyn Ryan, who's now the managing editor of the paper. There was this sense so that like, there was certainly blow, you know, there were certainly people were angry internally. But there were also a lot of, I think a lot of, a lot of reporters saying like, we need to be writing about this stuff that it's not been good that we've just been cowed into silence. And again, not silencing like saying, oh, well, you know, whatever, you know, pick your, you know, like the opposite, like, oh, well, this shouldn't happen transgender should not be whatever, but just like right about it. You know, you're right about like transgender and sports like let's take a real look at it. Let's not get cowed. And so yeah, it was so so was an interesting time. I mean, I, you know, there was certainly a lot of blowback but there was also like there was a sense that, you know, what you like as a journalist that you're like writing on stuff that's important in the moment. And yeah, so, I don't know, I'm not sure if this wasn't this wasn't the era and I was at this time I was writing and had been writing actually about sort of different activism in Portland, because I still lived in Portland at the time. Since 2019, and it really became it's so you're you're completely correct that COVID instead of saying like, wow guys we can't really can't fight about this stuff because COVID so important, it was an accelerant. It was like, oh hey, you want to fight here's here's again here's the next rage calorie thing that just amplified all the other stuff, but it really became the era and you've recently wrote about this too I believe of advocacy advocacy journalism you were told and I, my sense I'm actually I know this was happening in some, you know, small segment of the New York Times building in terms of more activist journalists was certainly happening around the protest where you were told if you did not side with the protesters, then you were part of the problem, you were going to keep Donald Trump's, you know, plans in action, and you really basically shouldn't have a voice, which is just so nonsensical. Because first of all, if you're, you know, incredible journalists, you can write, you write what you see, I'm really happy to have heard that you had support within the building because we don't hear about that a lot what we hear about are, you know, the sort of small, but loud activist class, which of course also had the support of the is it the newspaper guild what is it called. Yeah, and then you know we get these stories, for instance, and I'm not sure how much you would want to talk about this but for instance with Donald McNeil. I really lost my mind out of Donald McNeil who I do not know personally being drummed out of the building and I, I feel very strongly about that I wrote a great deal about it for different publications and I, as I recall. In a pretty anodyne tweet supported me getting that correct. You're getting that correct. Yes, and I still do support, you know, so do I. Do you want to tell so if for people that don't know and I'll put some links in here in the show notes Donald Neil had been at the paper literally since he was like a copy boy for 35 years he had risen through the ranks he had become like the main science writer at the New York Times. It's covered who do you want there except someone writing that's kind of got the chops. He was doing it. He was going to be or he was up for Pulitzer for his writing and something that had happened. Three years earlier or four years earlier while he was on a New York Times trip, which is one of these trips that, you know, young people can pay a lot of money to go to a different place. Yes. Right. Yes. Right. And he was in, he was in South America. I can't remember what country Peru and he was sitting with a bunch of kids and there was a high school girl who said, you know, what do you think about this particular situation. There was a girl in my class who, you know, you know, use the N word and he said she used the word and he repeated it back to her saying, well, was she quoting something or was she actually using it because, you know, context matters. And, and so apparently, because it was 2017 or 18, whatever years I'm sorry, not remember, it got back to some parents and they complained and, and, you know, Donald McGill was called in and he was kind of reprimanded, but it was not a really a big deal. But bye. Oh, excuse me, until 2020, when certain people within the paper disinterred it, wanted it to him to be essentially tried again. And he was. And I'm really summarily drummed out, including Dean back K, who was the editor at the time, saying, you know, what was it that context doesn't matter. I remember the exact quote. And I think for a lot of us and I'm sorry for this long sort of throat clearing here and explanation. It was so bizarre and so wrong and so infuriating. You have to speak up about it, because if, because you can't just, sorry, I'm talking too much let's let's let's go to you Michael Powell would know your, your, your, I mean you're both, you're both capturing my, my outrage at it and also I mean accurately saying what happened The Daily Beast revived it in the middle of all this, you know, the craziness post George Floyd, you know, really scurrilous piece I mean just a scurrilous piece of journalism, a bad piece of journalism. And Dean, by K, who I, you know, really very much admire and a lot of respects and is a terrific journalist I mean this was not his best moment. It was not the best moment of the New York Times at all. And, and there was just a sense that they, I mean, you know, Don Donald had, I mean, he was, he covered infectious disease he was arguably at that point, the most important reporter at the New York Times I mean he really wrote with authority. It's New York City, yes, adults and sounds of New York City. But you know, and at that, at that very moment when he's being, I mean, fed it and properly so for like just like writing with real clarity he's, you know, treated as like Bull Connor, you know, like that he's like saying the N word and throwing it around. And it was just so idiotic. I was also on the new I'm on the, I was at that time I was on the, oh, I don't know it's essentially the executive committee of the of the guild the news guild at the New York Times that's the labor union. And we were getting pressured from the head of the, of the guild in New York, the president to, you know, well, you know, we had an obligation to speak out. And it's like, what the hell are you talking about? No, we have a primary obligation, whether we like it or not, even if let's assume Donald really acted improperly, we have an obligation to defend our members. But in this case it was particularly appalling because it was kind of like, no, we're not going to be, I mean, the argument was that we can't be caught on the wrong side of this argument. And it was just a wrong side in the wrong side. No, it was a pernicious argument. And, and it destroyed his career at the New York Times. I mean, he ended up leaving and, you know, at the same little bit earlier, you know, there'd been the whole battle over the Tom Cotton editorial, you know, I know it very well. I'm sure you do, you know, I mean, Tom Cotton, very conservative, very influential Republican Senator writes a, you know, an op ed, an op ed, not editorial. So I, I, you know, saying that they should call in the National Guard, which by the way, was happening. So, whatever one makes of the argument, I mean, you can oppose it. I mean, that's a whole point of an op ed page, right? Did you get a variety of voices. This was a very important perspective at that time. And cotton had real lines into the Trump White House. So if you're looking to do what op ed pages do, you want to reflect that somehow. And, you know, we, I had, again, in this case, I mean, you know, that was a case where I had colleagues who, like, I really respected, but I mean, we're making these arguments, you know, this, this op ed puts us in danger. And it's like, oh, just, you know, stop. No, it doesn't. And I mean, we're journalists. We're out in the street. We cover. I've covered a great respect for the people do, you know, you cover riots, you cover demonstrations. I mean, we have obviously very brave reporters cover war zones all the time. I mean, it's, you know, that's part of being a reporter. But this notion that it, that, you know, running an op ed by a US Senator endangered. I mean, that was actually the probably that and Donald McNeil, where the two moments where I thought like, you know, this, this is just, you know, we've lost our way. We've lost our bearings. And, you know, frankly also to the two incidents in which the newspaper reacted very badly. But, you know, AG Salzberger, who I know a little bit, I like, but was very new to being, you know, just taken over for his father, I don't know, late 30s early 40s, and this was not his, this was not a good moment for him. You know, I mean, people, there were, there were essentially were apologies for running this. It was a bad, you know, it was just a bad moment. I do think the times has gotten, you know, is corrected more so I mean, there's still things that, you know, but, but I, but that was a really bad moment and therefore an interesting time to be doing what I was doing, which was covering all of this stuff because you're seeing it happen within the paper and I did and other and, but I should say others did. I mean, I spoke up on the, the cotton thing and, you know, I said this was not a good moment for your times at all and others spoke up. But certainly that was a case where I think there were what was some like 1200 signatures, you know, opposing the cotton thing. There were hundreds of reporters saying that Donald McNeil should be fired. I mean, that was a bad moment. I tweeted the other day that it by the grace of God, let the, let the, the, the era of the group letter have passed because it's just, we're so done. I'm 100% in agreement with you with you on surprisingly about the cotton op-ed. It is an op-ed. It's an opinion piece. We have an, we have a responsibility, not just as newspaper people, but as humans, hello, to listen to other people's opinions. You can scrap it out. You can say, I don't like this, but to fall back on this like, well, we're not safe so that you get your way is really, really, it's really lame. Okay, we're supposed to be smarter than that. And I also think, and this could be cynical, but I mean, we know that, you know, Barry Weiss, who was part of the opinion pages, then her head rolled. Of course, she's wound up, you know, in Clover, which is great. And it, sorry, I'm losing my turn of thought here. Sorry, what was I going to say here? Oh, I know what it's going to say. I remember doing an article a little bit after the whole cotton incident, I believe for the dispatch and talking to a few people who said, you know, when Barry got there from the Wall Street Journal, she was really courted. You know, cameras would come into the building and they'd want to quote on something and she was, you know, she was smart, she was personable, she was cute, like, they were always going to bury. And it is just absolutely obvious that that is going to engender, maybe a little jealousy in your colleagues. And I think with Barry, I think with Andy Mills, who was part of the daily, I think with Donald McNeil, I think there was either passively or actively this idea that, well, if we get rid of that person, then maybe there's more sunshine for me, which is not the way the world works. I mean, the world will do the work. Yeah, I think there's that. But I also think, well, yeah, particularly within like the opinion pages. I mean, there were a lot of, there were a lot of very, at that time, kind of left leaning. I hate these words. Like, like the word I've never used in writing woke, right? But I mean, sometimes they were, they woke staffers who like, or, you know, who thought they were woke. And so I do think that what you're saying is true, I think, you know, she had a high profile. But there was also a sense that she was like, you know, she was on the wrong side of this stuff. You know, we have to like, you know, we're going to, you know, we're going to whack her when we get the chance. Sure. Well, but I agree with you. The Times has rited the ship. Joe Kahn did that long article with Semaphore. And speaking of Semaphore, so Max Tanny was one of the writers of that piece in the Daily Beast. And I was absolutely livid, but he's turned out he's actually really good writer. He's a really good reporter. And it makes you wonder sometimes, is it the writer, or is it the publication that is demanding the coverage. That's right. I didn't actually realize that he was the writer of that. Yeah. You know, I think also I mean, look, co writer, you know, be really, not just kind, but I think also really like, there was, there was a certain moment, and that was one of them where people just kind of lost their minds. I mean, I have good friends who signed that guilt letter, who, like I was shocked to see, and I don't think that they did it dishonestly, like, you know, that was around the cotton. Like, I just think it was one of those moments where, you know, people are swept up like in a raging, you know, river of, you know, kind of righteousness and fear and anger. And you want to show that you're a good ally, you know, to African American reporters. And, you know, so I'm, you know, I'm willing to like, right, I mean, to think that like someone could look back three years later and think, Jesus, what was I doing, you know, do you think that some of those writers would write the same letter, obviously we're in a different era. So we're not having those letters, but do you think that, like, now that the temperatures may be cooled, our fever has gone down a little bit like do you think they would sign that kind of letter now. That's a good question. I think it would not be nearly the number. I, you know, I think you would look, there's a, you know, there's a certain percentage within the time some of its generational, though, by no means entirely. So I think somewhat, but I don't think you'd get 1200 people. No, I think that there's, and I don't know that if I were to go to, you know, a bunch of those who signed that they would now tell me, Oh, you know what I was like wrong. I mean, that isn't always how we work right. No, but I think they might not. I think that I'm sure in fact that there are some because I know, you know, some of, as I say, friends colleagues who signed it, who I just find it like almost impossible to think that they would sign that same letter today. But then of course, then the error of the next letter comes out. So we'll see. I've had a few people in my life. Thank me for reporting. I've done about things that, you know, just trying to really report what I saw what people told me and maybe it wasn't popular, but this is how I saw things made them feel less crazy during the pandemic. And I said that to you in the opening. And I want to especially thank you for the piece that you wrote about jihad rehab, now renamed the redacted, which was a documentary about Saudi and Yemeni. They've been prisoners in Guantanamo and then they were taken to a rehabilitation center in Saudi Arabia. And I'm for Meg Smaker was the filmmaker, an incredibly interesting story of her own just an absolutely bizarre trajectory into like I think she was like, wasn't she like a martial artist at some point, and she was a firefighter teaching firefighting and Sana Yemen, and just like this crazy crazy life story and she makes this film which I saw, which you still cannot see, but I was in touch with maker and she sent me a copy and it is. I mean, I could almost be overcome with how incredibly beautiful and important and surprising and moving but also sort of calmly she told these men's stories she gave them an opportunity to tell these stories and she was completely crazy and rightly celebrated for it, including, you know, getting into Sundance in 2021, which was like, it was COVID and like, nothing was happening and Abigail Disney was a big supporter. She was rightly celebrated for this tender and stupendous work and then whoops. I guess she wasn't. I guess there were a few people that felt that because she was not of the same descent as these men as these men that she should not be allowed to make this film and you want to talk about a deep platforming. This might be the biggest I've ever heard about so could you just talk about her story for a second. Look, I mean, again, you summarize. No, no, no, you would summarize it extremely well. I mean, it was appalling. I mean, I, when I, you know, and you never know when you embark on these things right, you know, you, I wanted to see the film first before I talked to her. You know, because sure who knows right maybe it's this, I don't know, egregious bit of magic prop or whatever, but she, she did this she took three guys or guys who had come out of Guantanamo. It was a wonderfully nuanced piece. It was humane. I mean, it wasn't, it wasn't, you know, you could, you could harbor your thoughts as well. Well, this guy make it or not and does, you know, I mean, it was complicated. Right. I mean, it took the full complication of human life. Right. And what could be more complicated than guys who had been caught up in jihad. Right. I mean, you know, with the Taliban or with or whatever. But it was this very humane attempt to wrestle with all of that. And with what they were wrestling with and the, you know, the kind of mutability of the human spirit. I mean, just all kinds of stuff. And, and she spoke Arabic, you know, and she had lived in Yemen. I mean, she had kind of done everything. You know, that one can to kind of understand and yet at the same time without, you know, falling into, as I say, one of two categories, one of either condemning them, or of like turning these guys, you know, these guys are all just victims, you know, these that they are of a, you know, an imperial estate or whatever she didn't do any of that. It was just this. And I can't help but think, you know, that had this come out five years before, earlier, say 2015. I just think it would have been a celebrated piece of journalism, unbelievable access that she got to these guys. I mean, this is a, a forceful, strong, intelligent woman who convinced somehow the Saudis to let her in. I mean, I don't even get it. And, you know, and, and, and that was one of the most striking, as you say, Abigail Disney who covered herself with shame in this. But, you know, she had a producer of this. I mean, there, there had been all of the kind of markers of sort of high liberal culture. And initially, he said, Oh, this is great. This is fabulous. Same thing that we're saying here. And then essentially her problem was that, you know, she was a white, you know, non Arab woman. And, and that became weaponized and then it like at some, it got crazier and crazier where, you know, she's like, you know, she's taken advantage of these guys she's, you know, they're, I'm trying to like now think I mean it was just, it got crazy. She was putting their life in danger was the right. Yeah. And it got crazier and crazier and she just, right, it's funny. I did a number of pieces where, again, a word I never used but where one could argue that not even argue where it was about kind of deplatforming. But this was the purest one. This was like, or canceling or whatever word you want to use. I mean, she just had her career. I mean, there was an effort to destroy her career. And, you know, this woman, I mean, she comes out of a working class middle, you know, lower middle class background. It's not like she came in with any money. This isn't, you know, one of the Kennedy's making, you know, nice documentaries. I mean, you know, the ability or the will to destroy her was real. And, you know, I don't know. I mean, I haven't talked to Megan several months now, but I mean, I, you do worry. I mean, you know, taking on somebody like Abigail Disney, who's one of the grand, you know, kind of grand doms of left liberal documentaries is a very dangerous thing to do. And, and that was a case where I thought like, yes, but the times like that piece. I should not have done that piece. I mean, that piece should have been done by one of our arts reporters. And, you know, and, and, I mean, one of the fun things and having the beat I had was that I had all these stories I could do. I mean, I just, you know, but part of that wasn't good. It was because there were in a number of sections. And I wouldn't touch this stuff. I mean, her story was known, you know, within, I mean, I know there were other reporters who were aware of it. But this is what she ran into. I mean, that people, people knew what was going on, but wouldn't write about it wouldn't speak about it. And I would say that really, I just don't respect that. I just don't, especially if this is your if this is your beat, like you got to do it, man. And if for nothing else for your own edification education, but you know when I went back and was saying that there was some maybe some jealousy in the halls against Barry Weiss and the people that were sort of piling on against her, you know, the people that piled on against maker initially were young or I don't know if they were young, but they were Arab filmmakers, mostly women. Let me not get started on how cruel women can be to other women, but besides that, I really have to wonder, you know, okay, you can, you had a successful campaign against a beautiful film that should be seen. Okay, you won. What did you win? What did you win? You didn't make the film. So you, it's you, you, you all you did was you knocked something down. What did you build for yourself and for the rest of us. And that's what I find a lot with this cancellation stuff. It's super easy to knock things down. It's pretty hard to build things. And so you think you're going to take a shortcut. And if that person doesn't get the sunshine, well, then maybe it'll come from me or whatever. I mean, if I were a young filmmaker and I had seen this, I would have like said, can I please take you to dinner? Can I knit you a quilt only because you're so amazing. And even if I just, just to be in your presence, this would be amazing. And that is not, that is not what happened. But you know what, Michael, speaking of being white, you're a white dude. Right. I think so. Yes, you are. And you walked into a world where, you know, there could be a bunch of people that said, wait a second. This, this Michael Powell dude, this white dude from New York City. Why does he get to go to the Navajo reservation and spend an entire season with a bunch of young dudes playing high school dudes playing basketball. And they're incredibly interesting coach. Why does he get to do that? And oh, not only why does he get to do this. We don't want him to do that. We're not about that. But you know what, Michael, I don't think that's happened. No, it didn't happen, actually. And yeah, I've often thought like this whole notion that like you're, that you're defined by and constrained by your identity. I mean, like, I had been told coming into journalism. You know what, what you can do is cover like white middle class, you know, middle aged white men, like, I mean, not to say, I mean, there's interesting search, but like how dreary and boring that that could be the, that would define kind of the parameters of the possible. And how fine do you shave it so my last book was about a woman through her two young kids off a bridge, and she, you know, killing killing her son. So, should we only have mothers who killed their children right that book. Is that is where we're where do we draw the line where do we stop. Well, I am going to posit as someone who spent a very long time in the native world. My daughter's late father was a full blood native dude and I been, you know, native folks have been part of my family since 1985. I'm going to posit that this didn't really happen to you because native song can do that. They can be like, I mean, not that it's like super like open the door. Come on in. Yeah, we're going to show you everything because it's not like that. But it's you want to visit. Okay, come and visit, come visit, come hang out. We'll be letting things out. Slowly, you're going to be noticing you're you're not going to be noticing. And before we keep talking about this, I'm just going to remind listeners that the name of the book is Canyon dreams. The basketball season on the Navajo Nation. Michael, this book, I had a very unusual experience with this book in that I got about a third of the way into it and I felt as though I were living inside the book. I wasn't reading the book anymore. I was inside. I would be reading and I'd find myself like gasping or having to stop because things were so. Well profound, actually. They were so profound. So, first of all, congratulations for this incredible book. I want to hear how you got there, how you did it. And then let's talk about this book's future. Well, thank you. I mean, I look, I ended up there through, I mean, indirectly or not directly actually through my wife who's a midwife and she, a long time ago when our kids were a little in the 1990s, we, she was, she's a midwife and she was working at the Indian Health Service for about four or five months filling in for people in vacation. So we lived on the Navajo res and it really got, you know, kind of under in the best sense, the word under our skin. I mean, just that whole the culture, the world. It was very much as you say in it, and, and, and this was both true and we live there the first time and then when I went back is, you know, it's not like, I don't know what's what I'm looking for it's not like, you know, we're Gary's Oh, come on in, you know, but you just approach it. Comely with just respect, and you talk to people. They let you in and you keep showing up. And, and, and I, you know, so we were both kind of fascinated but she had had a chance to stay so it's always one of those things where, you know, you wonder of what roots you take in life. And many years later I had a chance to go back for the New York Times and I was out like covering up Super Bowl and Phoenix and that's just like, anyway, it's like soul crushing it just who needs it. So I said, let me go, you know, like, I knew that they played basketball up there on the resume up there it's like at 7000 feet so you have to go up on a plateau. And, and I went up there and you just found this other world and you Navajo is a gigantic reservation society West Virginia. So it's, so the really is the sense when you're on it that you're in another world. I mean it's some United States, obviously, but it's, but it's just a very different place. And, yeah, and I did some pieces on a, on a, you know, this, this gently basketball team I met this wonderful complicated coach was, you know, evangelical and, and a Native American and part Mexican grew up in extreme poverty. And, and they just kind of opened up to me and, and, you know, I remember when I I'm jumping around but when I finally went out there to do my book. You know, the first I lived out there for like six or seven months and the first month I was like really like, you know, I'm lying bed and think like I've got to reach out to so and so and so and so I've got to like, and like, basically I just needed to like chill the F out like just that's right. Just be quiet and it will. And sure enough, as I started to do that, it started to happen. You know, I would get invited to a dinner with, and you realize like whenever you get invite, like, a family invites you to a dinner, but that usually means like 25 people, you know, and you're having, you know, Navajo tacos and you're talking about. But it's also the sort of wonderful aspect where you're talking about life. I mean, we're talking about like, you know, mystical beliefs, how you go. And I just didn't say, I mean, we know all the problems that Native Americans have, right? I mean, you know, alcoholism, poverty. I mean, there's all, you know, there, that it's, it's, they're very human, like all of us, and they have all those problems, but there is this, this sense of belonging, I guess, that I just really appreciate it. And then the willingness, sometimes astonishing of people to talk about some of the pain in their life. And yeah, so anyway, it was, yeah, it was a very, it was a very wonderful for me selfishly. It was a very wonderful experience. And you're absolutely right. I mean, look, I'm an angler, right? No, like, I'm not going to like, you know, I could, I could wear turquoise, but it isn't going to make me look Navajo. Dreamcatcher. Yes, exactly. But, you know, but that really didn't become a big, I mean, they were understanding. So they, let me, you know, as you become friends, let me explain this stuff to you, but it was also kind of funny. I mean, they call themselves, well, DNA, which is Navajo. They also call themselves Indians. Oh, yeah. You know, I mean, I used to say with my daughter, I would say, oh, she's, you know, she's American Indian people would be like, you have to say Native American, I'm like, well, actually, they say skins. So I'm just going to tell you, I'm just going by what, how they act. Okay, but you do you. The second game of the, of the season that I covered, they were one of against one of three teams that were named the Redskins. And these were Indian, you know, these were native tribes, sovereign, native towns. So, you know, yeah, yeah. Yeah. So it was, but it was just a one, it was wonderful. And that was actually, I mean, it reminded me of. Go back to what we were talking about. One of the things I love about journalism at the best is the ability to enter another world. Right. And, and, you know, to work your way towards some understanding of that place. And, yeah, so that was just great. Because they also unspool it to you. It is definitely, I mean, it's definitely the case that we should all, we should always externalists just like sit and listen when we go to stories, you can't pre decide anything. One thing that I know and that you, of course, know now is, you know, a lot of the ways natives have been covered has been, you know, either like, oh my God, the destitution, the horrors is just so terrible, or these mystical beings. And it's like, yeah, no, you know what, these are folks and they eat and they poop and they have children and they have tragedies. And yeah, there's alcoholism. Guess what? If you drank 68 beers, you'd get drunk too. You know, it's not just that they're like these special people. And yet. And yet. There are certain things that, and you really did this well. Man, I lay in bed just thinking and thinking about this. How do I say this without sounding patronizing or like I know things I don't know. There, there are, I guess there's spiritual elements to everybody and I even think spiritual element is the wrong way to put it. There's certain understandings that are things we don't, we can't really see, but they were there, whether they're just past the veil or whether it's a permeating between the ancestors and yourself or the moment and yourself. That, that's real man that things happen. And I've actually experienced a few of these things that, you know, I've tried to explain, I'm not going to explain them here to a few people that like, yeah, they, I can't explain them, but it was when I was in contact with my native peeps. Yeah, I agree. Yeah, no, no, I agree. I mean, it was, again, without like getting, you know, woo or whatever, but like there is, there's a permeability between worlds right and the material and the immaterial and stuff that was just moving and fascinating. And I don't, you know, I became friendly with a couple of medicine men, but they were interesting guys, like these weren't like, you know, I mean, they were rare roads, they did, you know, they drank too much. They had all the kind of, but it was, yeah, I mean, well, to pick one, I mean, like the coach, who's great guy, about 70 years old, you know, and he describes being because he'd also coached on the Apache reservation. And they sort of, you know, cousins of the, of the Navajo and they're both Athabaskan tribes, and they also have a similar cosmology and he describes, you know, coming back from a game. And then he was late at night during the winter and, and he, there's this huge white eagle that kind of comes down, like literally to like the crash into his, and it looks like it's going to into his pickup truck. And at the last second it shoots up. Like at the last second, and his daughters behind him was a school teacher. And the, the, you know, our lands, turns into a man, and runs off the thing. Now, you know, I don't know. I mean, I know that these people are both T toddlers. They're both wonderful people. They're frankly actually because he's an evangelical. He's like, you know, on an odd relationship to a lot of Navajo cosmology and stuff. I mean, kind of buys it and doesn't and this and that. But like, and both of them told me this. I mean, just matter of fact. I, you know, I find that wonderful. I do too. The one I remember from the book is the team is Martinez's team is going to play and they get to this one arena. And I think the way you described it is the ball players limbs had turned to iron. And they, they come off to the coach and they're like, there's a cloud, there's a cloud, there's a cloud over the court. We can't like they couldn't do it. And it turns out later that I think four of the medicine men from that tribe, but a gone into the locker room and sprinkled something. But the part that just blew my mind is they stood. And these games, by the way, for the listeners, and you've got to read the book. Okay, it's not like when we go to a high school basketball game. And it's like, answer is there. Yay, honey. No, there's like 5,000 people crowded in and they're screaming and they've driven like three hours through the snow to watch these boys play. And these medicine men, they, they stationed themselves at one at each of the corners of the top of the stadium and very quietly chanted. Yeah. This is medicine man. Now, do I understand it? I do not. Is it, does every human on earth probably have access to this permeability? Good way to describe it. Yes, I'm sure we do. But for some reason, history, how they are, or at least that we see natives have access to this more, or we're noticing it, who knows, I don't know, but I'm with you. I believe it without having to particularly celebrate or anything like that just is. No, no, I agree. It was very, yeah, it was very moving. I mean, that that whole trying to make sense of that and, and, yeah, it's, it's, yes, it's a wonderful other world. So, you know, we have had in the past couple of years, we've had in the media, we've had some hey, we've had some more, we've had some more native representation. I wrote about a little about that for the free breast because my late father-in-law was Will Sampson, who starred in One Flow with the Cuckoo's Nest. So I've had access or been paying attention to natives in the film world. I mean, it was so awful back in the day when I knew Will. He's like, yeah, and I don't know if this story is true or not, but he told me that they were going to consider Chief Dan George for an Oscar for his part in the movie Little Big Man, and then some people on the Oscar Committee said, but why are we going to give an award for an Indian playing an Indian? It's so, it's, it's so disgusting. But in any case, we've had some films, including a film that's doing very well called Fancy Dance, that my daughter was the set ticket on, starring Lily Gladstone, who starred in Killers of the Flower Moon, who also had a guest part in Reservation Dogs. My daughter actually appeared in that too. She's was a set decorator. I love my show. Yeah, so Sterling Hargia, who created that show. Okay, I'll tell a little story. I've told it before here, but we're going to hear it again listeners. So my daughter's dad, who she was like, they were attached died in 2019. And she really became a satellite and sort of like floated off from the world. She went to Memorial in Oklahoma, and this woman named Nan came up to her. Put her arms around her and said, your dad and I were like homecoming King and Queen at Indian boarding school. Wonderful. Nice. She's feeling more, you know, she was raised in LA important when she wasn't raised in Oklahoma. Okay, couple of months later, my daughter gets a call from this girl. She hasn't seen it 10 years. My does doesn't even work and film anymore and says, hey, I'm doing this project in Oklahoma. I don't know. It's native. I thought you might be interested. She said, well, what is it? Oh, it's a TV show called Reservation Dogs. You know, it's in filming in Okomogi, Oklahoma. My daughter's like, my father's fucking Okomogi. So, okay, she takes the job. Oh, she gets there. And it turns out the creator of the show is Sterling Harjo, who is Nan Harjo's son, the woman that put her on my daughter. Okay, so my daughter gets there and he's like, hey, cuz. So they're doing this show. And then this actress, native actress Irene Baderd is supposed to star in this role of Grant Granny in this one scene with Lily Gladstone. Oops, Irene Baderd gets COVID. Sterling turns to my daughter and says, you're up cuz my daughter's like, no, no, no, absolutely not. I'm not getting it from the camera. He's like, you're doing it. And she did. And it was pretty amazing. But, you know, what Reservation Dogs, fantastic, fantastic show. My daughter worked on it all three seasons. It gave you the native community, the way I've seen the native community, the humor number one, but also Yoda Respect. It was just a wonderful show. So you've, you've seen it. I take it. Oh, yeah. Oh, yeah. No, I'm a, I'm a big fan of it. Yeah, I think it's terrific. Yeah. And for that reason, it's just, it captures something and essence that's great. That we haven't seen that we don't see because it's always, again, it's like, you know, the braggled natives or the celebrated flutes in the background. So yeah, it's like real deal. And then Sterling Harjo is the co-writer of Res Ball, which is the movie that's been made out of your book. So tell me about this. Has this happened? Yeah, I mean, look, it's wonderful. And the movie's very good. It, you know, as they say, the movie's inspired by my book, which really means, I mean, they took it off and, and, you know, they made a, in the best sense the word, a fictional story, right? I mean, based on, well, not based on the book, but, you know, kind of like off of the book. But it's wonderful. I mean, I, it was, it was great to say. I mean, Harjo, I think is terrific. It's, yeah. So it's, and it's also wonderful. I mean, much like Res dogs. I mean, it is a native cast. I mean, there's, I don't know, I don't know if there's a white guy in it. I mean, you know, that's great. I mean, in that case, this is like, I mean, it's really well, it's well done. It's well acted. And it's, and it is great to, even as somebody, you know, I'm a white guy who wrote about, you know, about the Navajo, but it is wonderful to see that. That world, you know, brought to life in a way that feels much like in, in Res dog that feels kind of authentic to that world. Is there a character in the book, in the movie that you, or is it not at all? Okay. No, no, no, no character that's me and, and the coach. I haven't actually told the, my coach, this, but I mean, in the movie, he is a lesbian. Oh, I bet he'll get it. I mean, what are you going to do, but get a kick out of it? What are you guys? No, no, no, I mean, he's not a, he's not a bigoted guy at all, but I mean, I think, you know, he is, he is an assemblies of God, you know, Christian. So I think it'll, I think about giving it, you might give a spin, but yeah, so I mean, it's, there, there are a lot of changes made. That's all, you know, it's all fine, right? I mean, there's a book is an art form, a movie is an art form. They're not the same thing. So it's, and what I did love is that it does get at a real essence of Navajo in a way that I hope I did in my book and that I think, you know, they, they do really well. It occurs to me that if, if, you know, all of us, if we do our work really right, like, if we really do it right, you really honor the story. And I'm not saying this to sound like, Oh, and here's the little cherry on the Sunday of her interview. I really think that you honored these kids, these boys, the hardships they have in their life, the absolute epiphany of playing really great basketball, which you described so well. You can tell you've written about sports. I mean, it's just, it's just gorgeous, gorgeous stuff. And did you get on, did you get any response from any people in the book when you wrote it? Yeah, I mean, by and large, by and large, it was, or not even by and large. I mean, to the extent that I got response, it was positive. You know, there is a, there is a sense sometimes, you know, the res is so different, like, you know, it's just, you know, I sent the book to some people. I'm just, you know, you, you wonder how many read it, how many, you know, I don't know. I mean, and there's a whole bunch of people that, in this way, you know, a good thing about Facebook that I follow on Facebook and that follow me and we stay up on each other's lives and so yes, I mean, and what's right, what's wonderful is just that. Right, I mean, in fact, I had a number of, like three or four Navajo say this to me at the time, like, you know, essentially, I mean, they didn't quite put it this way, but are you going to stay in touch, right? Are you going to, you know, now look, I don't get back there, I have been back, but not nearly as often as I'd like. There is this, it's a frankly the one that keeps me caught on Facebook, you know, because it's like that is, for whatever reason, that's really the platform that they use, and it's where I can, you know, stay in touch with weddings and, you know, a few roles and other things so, yeah, I mean, overall it, yeah, it's just, it was wonderful, and it's a very interesting thing because you know you, there's some of the kids who I think have done pretty well are doing pretty well for themselves. There's others where, you know, I worry and I look at like, you know, the pictures and you just kind of, and there is that, you know, one of the tensions, some I dealt with a lot in the book is that, you know, there are kids who really should leave the reservation, at least for some period of time, like, you know, they're, they're, they're small, smarts more, because there's plenty of smart people in the rest, but it's just, you know, to have the opportunities to kind of see their lives flower. There's some who really need to leave. And, you know, and that's a hard thing right it's hard I even feel like strange saying it because I know their parents and I know they're, you know, but it's, it's a, it's such a complicated dynamic. It's hard to explain if you haven't seen it, and you will, in a sense see it if you read Michael's book which I highly recommend. Okay, Michael, we have come to that part of the show we're at ask you the very, very important and profound question, which is what's in your hotbox this week. Okay, well I'm reading and this is going to sound very highfalutin and it's not my, but I'm reading a, a seven story mountain by Thomas Mer. Oh, oh, I, well I didn't finish it but I read about half of it a long time ago like beginning a college I think. Tell us, tell us, tell me what I missed. And I really like and actually it's kind of interesting I mean it's in, in, in some way it's almost connected to what we were talking about with Navajo I mean it's about this, you know, this white guy who becomes a, you know, the ends up becoming a Catholic friar but it's, it's really about his, it's kind of a coming of age and kind of how he makes sense of the mystical and he would, this is pretty written pretty early in his life but I mean you know he would become very interested in Buddhism. And yet it's also I mean he's a very, very good writer so it's just, it's a, it's a, it's like a kind of a coming of age tale that also has a spiritual dimension and it's challenging for me because I'm not a Catholic. You know I mean he is, it's about falling in love with Catholicism so it's, it's, it's an interesting, it's kind of an interesting emotional intellectual challenge to read it. I mean he's not what's the word I'm looking for I mean it's not like he's a very kind of open to the world so it's not like you know you know I found the one true faith. It's interesting anyway it's just an interesting it's like falling in, it's like the story of his falling in love with a search for the spiritual that you know not so much from this book but from the arc of his life will take him in a lot of interesting directions. Anyway, so I don't know why I started reading it but it felt, and it in some way it really does bring me back to some of these themes that we talked about with the Navajo and others. When I revisit. So I started a book called small rain by Garth greenwell I learned about Garth greenwell with his first book called what belongs to you. I think it's about five or six years ago and I absolutely fell in love with this book it's a short novel and I want to rereading it something that you just love so much you have to read it again and I loved it because of the way he writes I think he also has a lot of history but he's one of these writers it's sort of like I've said before you know John Diddy and her William longest feature could write a 200 book about tying their shoes and I'm going to read the book. But they've been right exactly but they both both of these people have certain you kind of know the way they write whether it's their cadence the rhythm their delivery system. He does not have any particular cadence or delivery system that I could put my finger on he just can write I mean I started this book and it's basically about like the main character like going to the hospital and there's some tubes here and I'm waiting for this it's like this should not be interesting. He's completely riveted. He's just he's just an amazing writer and I highly recommend if you I mean I haven't finished small rain I can't tell you about it but what belongs to you I highly recommend it and I highly recommend him as a writer. That's great. Yeah he's great. Um, well listeners thank you so so very much stay with me Michael when we when we click off here thank you so much for joining us and Michael Powell. I love your work read read him in the Atlantic I'm so glad. Oh, one final question is there. Is there some secret reason you jump to the Atlantic. No secret reason other than challenge. I mean truly like like I mean several people have asked that you know always you know where you finally forced out of the times whatever no no I was not. I just wanted the challenge of trying something new trying longer form writing and yeah no and so I just I wanted that and I and I got it. That's it's wonderful another another great voice there at the Atlantic. All right well thank you everybody and we'll see you next time. [Music] [Music] [Music] [Music] [Music] [Music]