Wellness Exchange: Health Discussions

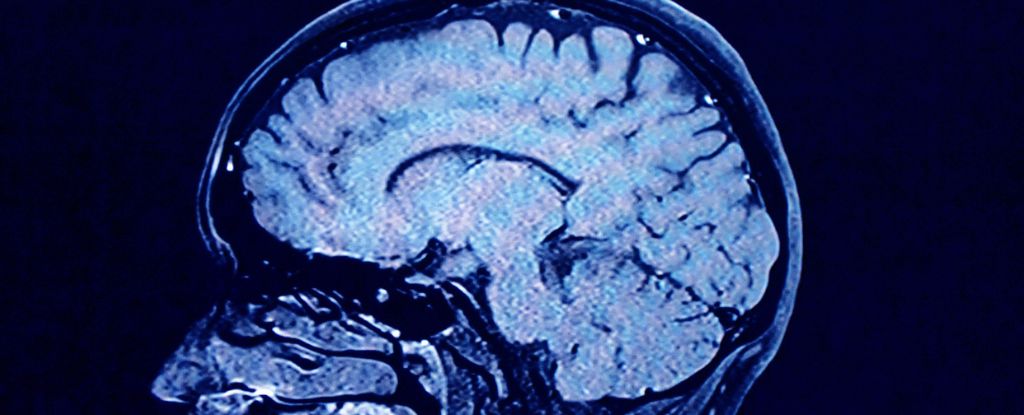

Brain Scans Reveal Hidden Fatigue in Long COVID Patients

(upbeat music) - Welcome to "Listen To." This is Ted. The news was published on Friday, September 27th. Today we're joined by Eric and Kate to discuss a fascinating new study on long COVID fatigue. Let's dive right in, shall we? Today we're discussing a new study on long COVID fatigue and its effects on the brain. Let's start with the basics. What exactly is long COVID and how does it relate to fatigue? - Well, Ted, long COVID is like the party guests who just won't leave. It refers to those pesky symptoms that stick around for months after you've supposedly kicked COVID to the curb. Now, fatigue is the big kahuna of these symptoms. We're not talking about your garden variety tiredness after a long day. This is the kind of exhaustion that makes you want to take a nap after brushing your teeth. - Exactly, Eric. But I think it's crucial to emphasize that this isn't just feeling a bit worn out. We're talking about a bone deep soul-crushing-- - Hold on a second, Kate. While I agree it's a serious issue, we need to be careful not to exaggerate. Many illnesses can cause prolonged fatigue and we shouldn't-- - Exaggerate? Eric, we're dealing with an unprecedented situation here. Millions of people worldwide are experiencing these symptoms. This isn't just another post-virus-- - All right, let's take a step back. The study mentions brain scans, which is quite intriguing. What did researchers find when they looked at the brains of long COVID patients? - Great question, Ted. The study examined 127 long COVID patients and they found some pretty interesting stuff. It's like the brain's internal communication system got a bit scrambled. They noticed altered patterns between different brain regions, particularly in the frontal lobe, temporal lobe, and cerebellum. Think of it as a cosmic game of telephone but in your noggin. - This is huge, Ted. These changes could explain why so many long COVID patients are struggling with memory issues, brain fog, and difficulty concentrating. It's like their brain's Wi-Fi is constantly buffering. This study provides concrete evidence that long COVID isn't just all in their heads, as some skeptics have suggested. - Now hold your horses, Kate. While the findings are certainly interesting, we need to be cautious about drawing sweeping conclusions. Brain scans can be tricky to interpret and still allow-- - But Eric, this is objective evidence we're talking about. The study showed that 87% of participants reported global fatigue and 86% had cognitive complaints. These numbers are-- - I understand the numbers seem high, Kate, but we need larger studies with more diverse populations to confirm these findings. We can't base everything on one study-- - Both of you raise valid points. Now let's put this in historical context. - Can you think of any similar health crises in the past that might shed light on the long COVID situation? - Absolutely, Ted. One parallel that comes to mind is the aftermath of the 1918 influenza pandemic. Talk about a blast from the past. Many survivors of that pandemic experienced a condition called encephalitis lethargica or sleeping sickness. It was like their brains decided to hit the snooze button indefinitely. This affected millions globally, just like COVID-19 and caused neurological symptoms that lasted for years in some cases. - Well, that's an interesting comparison, Eric. I think a more recent and relevant example would be the emergence of chronic fatigue syndrome or myalgic encephalomyelitis, CFS ME, in the 1980s. This condition is practically-- - Now, wait a minute, Kate. We can't just dismiss the 1918 pandemic example. It shows us that post-viral neurological complications can occur on a massive scale. It took years to understand-- - But CFS ME is so much more directly comparable, Eric. It's characterized by extreme fatigue, cognitive issues, and other symptoms that mirror long COVID almost perfectly. Plus, it demonstrates how challenging it can be-- - Both examples are fascinating. How do these historical events inform our understanding of long COVID? - Well, Ted, the 1918 pandemic is like a crystal ball for us. It shows that when a virus goes viral, pun intended, the aftermath can be just as challenging as the initial outbreak. It's a reminder that we need to be patient and thorough in our research. We can't expect to have all the answers overnight. - I agree that patience is important, but the CFS ME example is a stark warning. For years, patients struggled to get proper recognition and care. We can't afford to repeat those mistakes with long COVID. The similarities between CFS ME and long COVID are striking. Right down to the brain changes we're seeing in this new study. - We need to be careful about drawing too many parallels, Kate. Each health crisis is unique and requires its own approach. We have so much more medical knowledge and technology now. - But that's precisely why we should be learning from past experiences, Eric. We have the knowledge and technology, so let's use it to better support long COVID patients and guide our research efforts. We can't just-- - You both make compelling arguments. Looking ahead, how do you think the long COVID situation will unfold? What are some potential scenarios we might see? - I'm cautiously optimistic, Ted. I believe we'll see a gradual decrease in long COVID cases as natural immunity and vaccination rates increase. It's like our immune systems are going to superhero school. They'll get better at fighting off the virus over time, plus medical research is advancing at warp speed. - I wouldn't be surprised if we develop effective treatments for long COVID symptoms in the near future. - I'm sorry, but I have to disagree strongly here. I think we're facing a long-term health crisis that will strain healthcare systems for years to come. We need to prepare for a significant increase in chronic illness, even with treatments. - That's an overly pessimistic view, Kate. You're painting a doomsday scenario without considering the resilience of both the human body and our medical systems. We shouldn't underestimate our ability to-- - Pessimistic? I call it realistic, Eric. We're already seeing the impact on workplaces and disability services. This isn't going away anytime soon, and we need to be prepared for lasting-- - Both perspectives are worth considering. What about the potential for long-term neurological effects? How might that play out? - Great question, Ted. While the brain changes observed in the study are certainly concerning, it's important to remember that the brain is incredibly adaptable. It's like a biological transformer, always ready to reconfigure itself. Many patients will likely recover with time and proper support. We shouldn't underestimate the power of neuroplasticity. - I think we're seriously underestimating the potential for long-term cognitive impairment here. This isn't just about individual recovery. It could affect everything from workforce productivity to education systems. Imagine a significant portion of the population struggling with memory and concentration issues. It's not just a health crisis. It's a potential societal shift. - Kate, that's pure speculation without solid evidence. We need longitudinal studies to truly understand the long-term impacts. We can't just assume the worst-case scenario-- - But we can't afford to wait for years of data before taking action, Eric. - We need to implement support systems now. The evidence is already clear that long COVID is a serious issue. We need to-- - I agree, we need support systems, Kate, but they should be flexible and evidence-based, not driven by worst-case scenarios. We need to strike a balance between preparing-- - Well, it's clear that long COVID presents complex challenges that we're still grappling to understand. While there's still much to learn, studies like this one are crucial in advancing our knowledge. Thank you both for this lively and informative discussion. This is Ted, signing off from Listen2.