Get access to this entire episode as well as all of our premium episodes and bonus content by becoming a Hit Factory Patron for just $5/month.

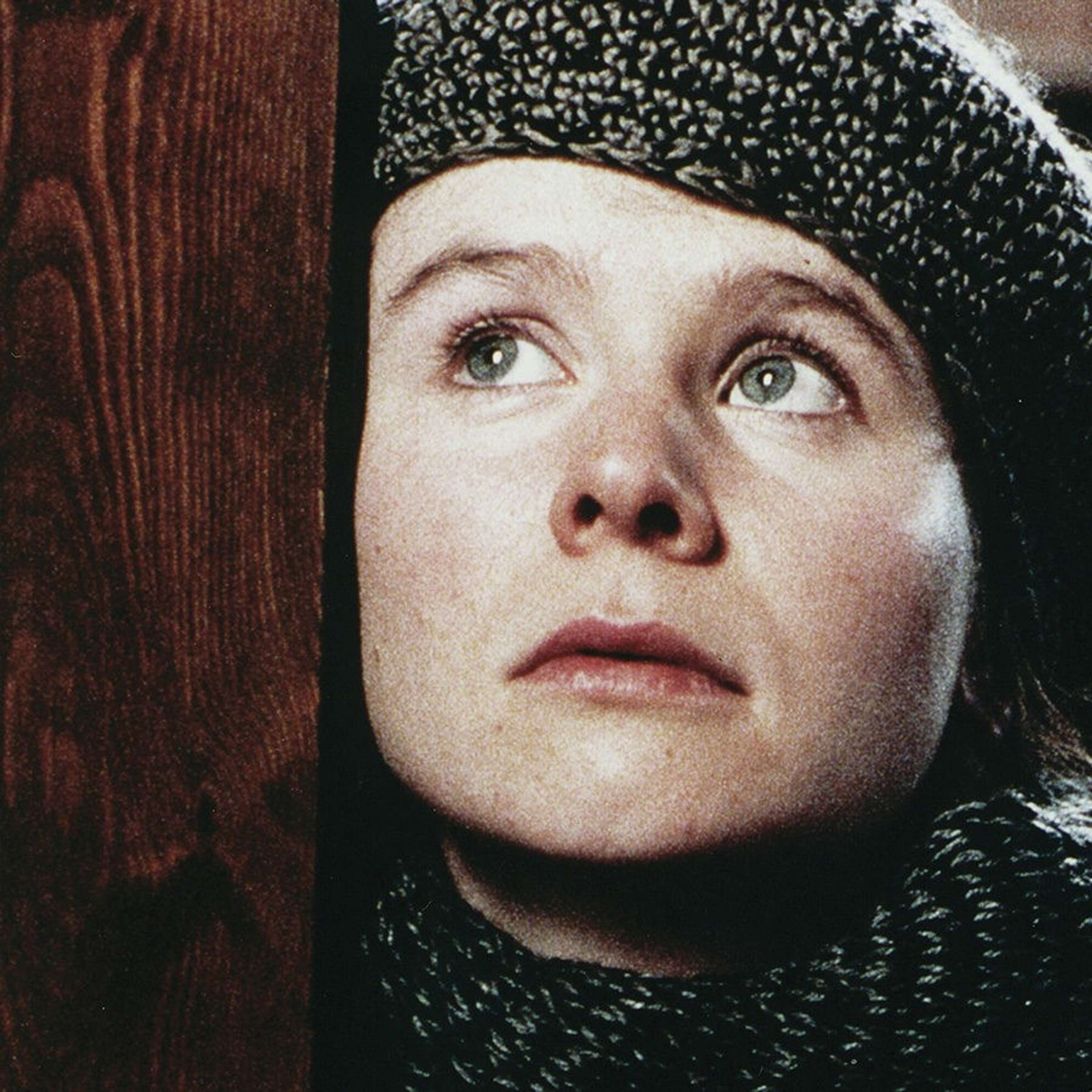

Producer and co-host of Die Hard On A Blank Podcast and recovering Lars Von Trier superfan Liam Billingham joins to discuss enigmatic Danish provocateur Lars Von Trier and his breakout Cannes award-winning feature 'Breaking the Waves' starring then-newcomer Emily Watson, Stellan Skarsgård, and the late Katrin Cartlidge. The film, set in a small comminuty in the Scottish Highlands in the 1970s, tells the story of Bess McNeill, a simply, godly woman who marries outsider oil rig worker Jan. When Jan is paralyzed after a work accident, he compels Bess to take other lovers in order to "keep him alive"...a task which she steadily comes to believe has divine connotations. Shot in 35mm 'scope with the great Robby Muller behind the camera, the film is a visually staggering work broaching difficult subject matter in the realms of faith, sexuality, and patriarchy all rendered in Von Trier's singular tenor, equal parts brutal, earnest, and cheekily playful.

We discuss the career of Von Trier, his work as a founding member of the Dogme95 collective, and the later period evolution of his storytelling. Then, we wrestle with the film's themes and execution of its ideas. Does the movie hold up for a longtime devotee and a newcomer alike? Finally, we try to make sense of Von Trier's oeuvre, and what - if anything - could be considered the trademarks of his style.

Follow Liam Billingham on Twitter.

Listen and subscribe to Die Hard On A Blank Podcast.

Read & Subscribe to Peter Raleigh's Newsletter 'Long Library'.

.

.

.

.

Our theme song is "Mirror" by Chris Fish

Hey, Hit Factory listeners, if you're enjoying and want even more Hit Factory, including the entirety of this episode, consider becoming a patron of the show at patreon.com/hitfactorypod. For just $5 per month, you'll get access to our premium bi-weekly episodes, bonus episodes, and a lot more. Thanks for listening and supporting. I mean, I think that I like thematically what's going on here, for sure. I, on paper, see a lot of the things here that become sort of fixations of Von Trier, and especially in what I've seen like Dogville, this film has a lot of the same kind of, a lot of the same kind of ideas brewing, the idea of kind of interlopers in small communities, but also the kind of toxicity of those communities in the way that what could be initially perceived as kindness or as a sense of community can quickly sort of descend into a kind of group think that ostracizes, condemns and villainizes people, brutalizes them. I like those moments of this film. I like what it's doing there. I just, I don't know, there's something about it that just felt kind of, and we've already talked about this a little bit. It to me was sort of like unbearably oppressive for long stretches of it where I felt like I was getting the hint without necessarily needing more of what was happening, and so much of it kind of felt perfunctory to me, which, you know, like the way that it's constructed the way it's designed, it doesn't feel often like Von Trier wants to settle into some of the moments that could otherwise be startling or kind of vicious in nature and really kind of hammer his points home. It seems like he's doing them and like kind of getting them in and getting past them as fast as possible to communicate the idea and get on to the next sort of moment where we are just sort of pondering. That sounds weird to say though, doesn't it, to be like, "I wish this movie was more brutal. I wish this movie was like more fixated on the brutality and then that's not exactly what I'm saying." Yeah, my actual feeling is that it is pretty brutal, but I think that it's like we're discussing within the context of when it came out and what that means. So, oh man, there's a lot to respond to there. So in my re-watch, which I hadn't seen the film in well over a decade, you know, despite my love for Von Trier, I'm not like going back to him all the time, I wish I were going back to him. But for context, I bought the tritarian Blu-ray of this, the week it came out in 2014 and I had not put it into a player until this week. So I'm certainly not sitting around like wearing a, breaking the waves hat, cheering to watch more Lars Von Trier movies, but he does occupy an important space in my life. But I actually did not enjoy re-watching this movie. I did not have a good time re-watching it. I found it brutal and punishing and very, I don't know, yeah, it wasn't a great watch. However, I do think that sometimes these attitudes about the films, and I'm not critiquing your response to the film here, I'm just critiquing what I feel like is a thought that so much, so very few people in the world, myself to some extent included, have never encountered a von Trier movie without the press around it. Every movie that he makes is like, he's a misogynist, he's a sadist, he wants you to feel pain, he's a nightmare, he's a Nazi, he's all these things. Most of which I don't really feel like I can say like 100%, he's not those things, but I think they're reaching as a statement. So I think if you were to encounter my feeling is that I think if you were to encounter this movie outside of its context, outside of his reputation as like a punishing auteur, and not like a punishing auteur in the way that Hanukkah may reinforce your attitudes about like European dominance in the world or the complexity of immigration, von Trier is like, he might be interested in socio-political ideas, I certainly think he is in Dogville, but he's doing something in this movie, I would say is interpreted as political, and I think your points about it earlier are great, but it's much more emotionally punishing right? But I wonder if we didn't encounter him through the lens of how he is viewed through the media if we would have a different feeling about this because I think Lars von Trier is a great example of like an earnest filmmaker, a filmmaker who's not, he's not hiding behind, despite the movies having strong aesthetic visions, he's not hiding behind those visions. He's like pretty, he once said that he was, the women represent him in his films and like, though I began this argument by saying that like we shouldn't interpret the ways we see something through the lens of somebody else saying it, I do think that that was spot on. I think there's an argument that like we're talking about a honest, earnest believer in the world and its possibility, and yet someone who has constantly observed the reality of that, and so I bring all this up just to say that like, I wonder how we would feel about this movie if we didn't have context for it before, because I think it's kind of naive and innocent, and I think it takes on the view of its main character, which is best, and it's like unbelievably astonishing performance by Emily Watson, and I sometimes wonder like if we were able to watch the movie through her lens, which I think would be a great act of empathy, if we would feel differently about this movie. Absolutely, and I mean, you know, Drear is one of the most distinctive and noteworthy reference points for Von Trear in his cinema and in his filmmaking. In fact, I read that Von Trear asked Emily Watson to study Renee Thakanetti in the Passion of the Mark to emulate for many of her facial expressions. Not only enough, I was reading about this in a Rosenbaum piece, Jonathan Rosenbaum, the great critic who mentioned on the show quite a bit, who I think is equally skeptical of breaking the waves while also finding it a vital entry in European cinema. He kind of says, you know, like something like this can only frustrate and aggravate me because it is so essential and so new and so like necessary to whatever things are going to look like moving forward. So I think this might be an interesting moment to bring up the curious reality of American mainstream politics in 1996 when this comes out and like the way Americans watched art films, because in revisiting this movie, I was like, man, they don't make them like this anymore, which was not me being like nostalgic, but this movie is almost 30 years old, right? You're getting very close and I feel like granted my like primo art film watching years were 2005 till 2017. So about 10 years after this came out and that's filled with like a certain kind of to be like very general about this European miserableism, right? So you had like your Bellatars, you had your Hanukas, you had your, but then you had this more like existential thing happening with Nuri built a chalon from Turkey, you know, and like maybe a more of an Antonioni existential, maybe not miserable except long, right? But not punishing, you're not being punished by these movies. And I feel like in the last 10 years on the whole, specifically as far as European art films had go, everything's gotten a lot lighter. Like things don't feel as like heavy, like drive my car while it's a sad movie is not a punishing movie, right? It's three hours long, it's sad, it's not punishing. Or anything really that you encounter now, I don't mean to say that it's not heavy or intense, but it's not necessarily like being sadistic and punching you in the face. And I, I, the only reason I bring this up is because I wonder if like for Americans in particular, really only, when you think about the 90s and like, things seemed okay at that time, you know, like from a certain American perspective, it was like Clinton's in office, economy's doing good, we're not quite at the like blowjob in the, in the, in the White House kind of thing. Sure. We're in the end of history. We're firmly planted in like the good times rolling, quote, unquote, unquote, we're not, we're not like, right, the old antagonisms are over. Now it's just capitalism. It's fine. And so this movie comes out and it's like, we have the ability to like kind of, oh, yeah, wow, shit, maybe things are bad for religious people off the coast of Scotland or whatever. I know that's, you know, it's reductive, but the movies are reductive and that, and how it portrays that. So watching it now almost 30 years later, when like things have changed significantly, at least from a, you know, from like a popular culture perspective, suddenly it's like, I can't hang with this shit anymore. Yeah. I don't have it in me. I have it in me. I struggled through this. I mean, I have a baseball hat on that, you know, right. And you know, maybe, maybe this is, maybe this is a reason why I struggled with it too. And what you're mentioning is just like things don't feel very good right now. Listen, I don't know if you've noticed that, but you know, to be clear, this is June of 2024, just so you know, you guys have noticed, but like things, things feel tight economically. We've been watching just like a brutal, horrific, like, I mean, I don't even want to call it a war. It really is, you know, like a brutal, like systemic slaughtering of people across the sea for like nine plus months now. And it just doesn't feel good to kind of, I think, like sit in this kind of oppressive milieu for this long. And it's interesting that you say this about the 90s, specifically, and I think that you're probably right that there is a cultural, maybe not appetite, but willingness to engage with things that feel like this in times of better relative comfort, right? Relative comfort. In fact, you know, like there's some interesting conversations while we're on the subject of Revan, who talks about his pusher trilogy and talks specifically about the first entry, which I believe came out the same year as breaking the waves in 1996. And he mentions this about the sort of Danish philosophy or ideology or predisposition where he's like, I made a movie that is about drug pushers, about, you know, people looking for the dark kind of underbelly and crevices of our society, because our society overall is rather good. Like we have a sort of social democratic system that doesn't really let you kind of fall through the classical-- Right, unless you pursue it. And I have to wonder if maybe von Trier without acknowledging maybe is tapping into that too, that there's sort of a willingness to trudge into these sort of dark recesses of humanity because everything else is a relative comfort.